3.3: Deeper Analysis of Nuclear Masses

- Page ID

- 15012

To analyze the masses even better we use the atomic mass unit (amu), which is 1/12th of the mass of the neutral carbon atom,

\[1 \text{ amu} = \frac{1}{12} m_{^{12}\mathrm{C}}.\]

This can easily be converted to SI units by some chemistry. One mole of \(^{12}\)C weighs \(0.012\text{ kg}\), and contains Avogadro’s number particles, thus

\[1 \text{ amu} = \frac{0.001}{N_A} \text{ kg} = 1.66054 \times 10^{-27} \text{ kg} = 931.494 \text{MeV}/c^2.\]

The quantity of most interest in understanding the mass is the binding energy, defined for a neutral atom as the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the mass of its constituents,

\[B(A,Z) = Z M_H c^2 + (A-Z) M_n c^2 - M(A,Z)c^2.\]

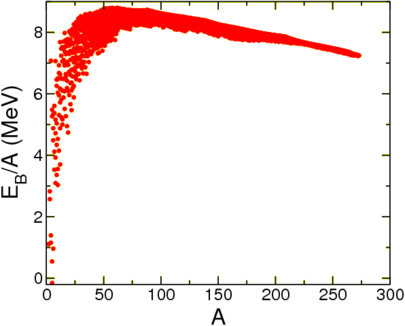

With this choice a system is bound when \(B>0\), when the mass of the nucleus is lower than the mass of its constituents. Let us first look at this quantity per nucleon as a function of \(A\), see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

This seems to show that to a reasonable degree of approximation the mass is a function of \(A\) alone, and furthermore, that it approaches a constant. This is called nuclear saturation. This agrees with experiment, which suggests that the radius of a nucleus scales with the 1/3rd power of \(A\),

\[R_{\text{RMS}}\approx 1.1 A^{1/3} \text{ fm}.\]

This is consistent with the saturation hypothesis made by Gamov in the 30’s:

saturation hypothesis

As \(A\) increases the volume per nucleon remains constant.

For a spherical nucleus of radius \(R\) we get the condition

\[\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3 = A V_1,\]

or

\[R = \left(\frac{V_13}{4\pi}\right)^{1/3} A^{1/3}.\]

From which we conclude that

\[V_1 = 5.5 \text{ fm}^3\]