11.1: Introduction- The Physics of Oscillations

- Page ID

- 22267

It is probably not an exaggeration to suggest that we are all introduced to oscillatory motion from our first moments of life. Babies, it seems, are constantly rocked to sleep, in many cases using devices, such as cradles and rocking chairs, that exemplify the kind of mechanical oscillator with which this chapter is concerned. And then, of course, there are swings, which function essentially like the pendulum depicted below.

In fact, oscillatory motion is extremely common, both in natural systems and in human-made structures. It essentially requires only two things: a stable equilibrium configuration, where the stability is ensured by what we call a restoring force; and inertia, which, of course, every physical system has.

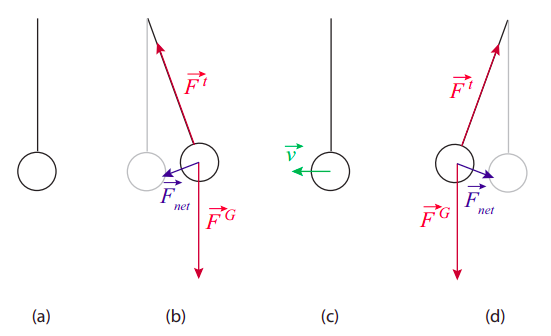

The pendulum in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) illustrates how these things combine to produce an oscillation. As the pendulum bob is displaced from its equilibrium position, a net force on it appears (a combination of gravity and the tension in the string), pointing back towards the vertical. When the bob is released, it accelerates under the influence of this force, with the result that when it reaches back the equilibrium position, its inertia (or, if you prefer, its momentum) causes it to overshoot it. Once this happens, the restoring force changes direction, always trying to bring the mass back to equilibrium; as a result, the bob slows down, and eventually reverses course, accelerates again towards the vertical, overshoots it again... the process will repeat itself, until all the energy we initially put in the system (gravitational potential energy, in this case) is dissipated away (or damped), mostly through friction at the pivot point, though air resistance plays a small part as well.

That the motion, in the absence of dissipation, must be symmetric around the equilibrium position follows from conservation of energy: the speed of the bob at any given height must be the same on either side, in order for the sum of its potential and kinetic energies to be the same. In particular, if released from rest from some height, it will stop when it reaches the same height on the other side. In the presence of dissipation, the motion is neither exactly symmetric, nor exactly periodic (that is to say, it does not repeat itself exactly—the maximum height gets lower every time, the speed as it passes through the equilibrium position gets also smaller and smaller), but when the dissipation is not very large one can always define an approximate period (which we will denote with the letter \(T\)) as the time it takes to complete one full swing.

The inverse of the period is the frequency, \(f\), which tells us how many full swings the pendulum completes per second. These two quantities, \(T\) and \(f\), can be defined for any type of periodic (or approximately periodic) motion, and will always satisfy the relationship

\[ f = \frac{1}{T} \label{eq:11.1} .\]

The units of frequency are, of course, inverse seconds (s−1). In this context, however, this unit is called a ”hertz,” and abbreviated Hz.