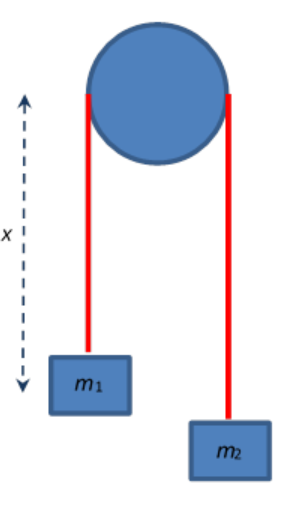

4.11: Example 1- One Degree of Freedom- Atwood’s Machine

- Page ID

- 29993

In 1784, the Rev. George Atwood, tutor at Trinity College, Cambridge, came up with a great demo for finding g. It’s still with us. The traditional Newtonian solution of this problem is to write \(\begin{equation}

F=m a

\end{equation}\) for the two masses, then eliminate the tension T. (To keep things simple, we’ll neglect the rotational inertia of the top pulley.)

The Lagrangian approach is, of course, to write down the Lagrangian, and derive the equation of motion.

Measuring gravitational potential energy from the top wheel axle, the potential energy is

\begin{equation}

U(x)=-m_{1} g x-m_{2} g(\ell-x)

\end{equation}

and the Lagrangian

\begin{equation}

L=T-U=\frac{1}{2}\left(m_{1}+m_{2}\right) \dot{x}^{2}+m_{1} g x+m_{2} g(\ell-x)

\end{equation}

Lagrange’s equation:

\begin{equation}

\frac{d}{d t}\left(\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{x}}\right)-\frac{\partial L}{\partial x}=\left(m_{1}+m_{2}\right) \ddot{x}-\left(m_{1}-m_{2}\right) g=0

\end{equation}

gives the equation of motion in just one step.

It’s usually pretty easy to figure out the kinetic energy and potential energy of a system, and thereby write down the Lagrangian. This is definitely less work than the Newtonian approach, which involves constraint forces, such as the tension in the string. This force doesn’t even appear in the Lagrangian approach! Other constraint forces, such as the normal force for a bead on a wire, or the normal force for a particle moving on a surface, or the tension in the string of a pendulum—none of these forces appear in the Lagrangian. Notice, though, that these forces never do any work.

On the other hand, if you actually are interested in the tension in the string (will it break?) you use the Newtonian method, or maybe work backwards from the Lagrangian solution.