29.7: Probability and The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

- Page ID

- 2763

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use both versions of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in calculations.

- Explain the implications of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle for measurements.

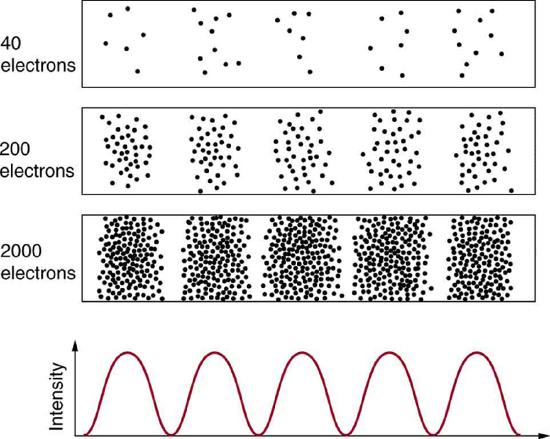

Matter and photons are waves, implying they are spread out over some distance. What is the position of a particle, such as an electron? Is it at the center of the wave? The answer lies in how you measure the position of an electron. Experiments show that you will find the electron at some definite location, unlike a wave. But if you set up exactly the same situation and measure it again, you will find the electron in a different location, often far outside any experimental uncertainty in your measurement. Repeated measurements will display a statistical distribution of locations that appears wavelike (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

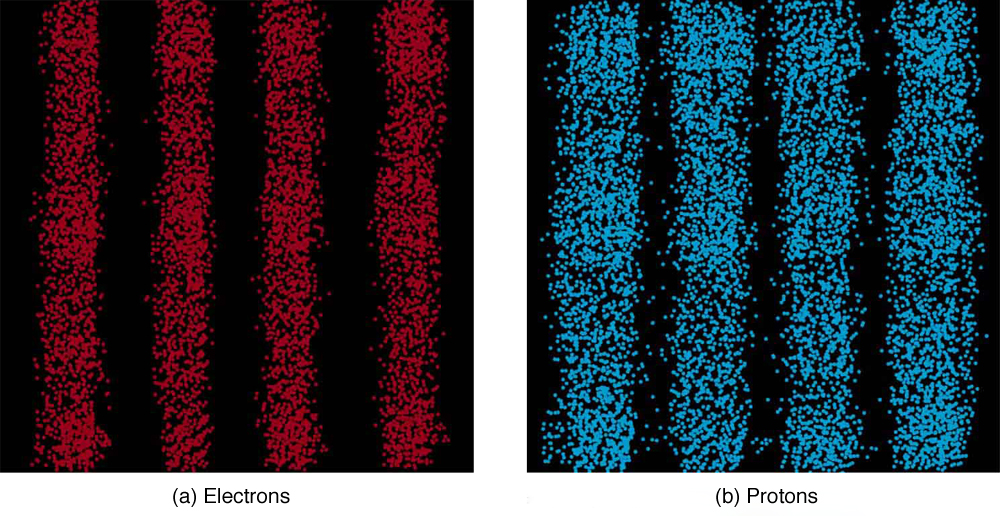

After de Broglie proposed the wave nature of matter, many physicists, including Schrödinger and Heisenberg, explored the consequences. The idea quickly emerged that, because of its wave character, a particle’s trajectory and destination cannot be precisely predicted for each particle individually. However, each particle goes to a definite place (as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). After compiling enough data, you get a distribution related to the particle’s wavelength and diffraction pattern. There is a certain probability of finding the particle at a given location, and the overall pattern is called a probability distribution. Those who developed quantum mechanics devised equations that predicted the probability distribution in various circumstances.

It is somewhat disquieting to think that you cannot predict exactly where an individual particle will go, or even follow it to its destination. Let us explore what happens if we try to follow a particle. Consider the double-slit patterns obtained for electrons and photons in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). First, we note that these patterns are identical, following \(d \, sin \, \theta = m\lambda\), the equation for double-slit constructive interference developed in Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum, where \(d\) is the slit separation and \(\lambda\) is the electron or photon wavelength.

Both patterns build up statistically as individual particles fall on the detector. This can be observed for photons or electrons—for now, let us concentrate on electrons. You might imagine that the electrons are interfering with one another as any waves do. To test this, you can lower the intensity until there is never more than one electron between the slits and the screen. The same interference pattern builds up! This implies that a particle’s probability distribution spans both slits, and the particles actually interfere with themselves. Does this also mean that the electron goes through both slits? An electron is a basic unit of matter that is not divisible. But it is a fair question, and so we should look to see if the electron traverses one slit or the other, or both. One possibility is to have coils around the slits that detect charges moving through them. What is observed is that an electron always goes through one slit or the other; it does not split to go through both. But there is a catch. If you determine that the electron went through one of the slits, you no longer get a double slit pattern—instead, you get single slit interference. There is no escape by using another method of determining which slit the electron went through. Knowing the particle went through one slit forces a single-slit pattern. If you do not observe which slit the electron goes through, you obtain a double-slit pattern.

Heisenberg Uncertainty

How does knowing which slit the electron passed through change the pattern? The answer is fundamentally important—measurement affects the system being observed. Information can be lost, and in some cases it is impossible to measure two physical quantities simultaneously to exact precision. For example, you can measure the position of a moving electron by scattering light or other electrons from it. Those probes have momentum themselves, and by scattering from the electron, they change its momentum in a manner that loses information. There is a limit to absolute knowledge, even in principle.

It was Werner Heisenberg who first stated this limit to knowledge in 1929 as a result of his work on quantum mechanics and the wave characteristics of all particles. (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Specifically, consider simultaneously measuring the position and momentum of an electron (it could be any particle). There is an uncertainty in position \(\Delta x\) that is approximately equal to the wavelength of the particle. That is,

\[\Delta x \approx \lambda.\]

As discussed above, a wave is not located at one point in space. If the electron’s position is measured repeatedly, a spread in locations will be observed, implying an uncertainty in position \(\Delta x\). To detect the position of the particle, we must interact with it, such as having it collide with a detector. In the collision, the particle will lose momentum. This change in momentum could be anywhere from close to zero to the total momentum of the particle, \(p = h/\lambda\). It is not possible to tell how much momentum will be transferred to a detector, and so there is an uncertainty in momentum \(\Delta p\), too. In fact, the uncertainty in momentum may be as large as the momentum itself, which in equation form means that

\[\Delta p \approx \dfrac{h}{\lambda}.\]

The uncertainty in position can be reduced by using a shorter-wavelength electron, since \(\Delta x \approx \lambda\). But shortening the wavelength increases the uncertainty in momentum, since \(\Delta p \approx h/\lambda\). Conversely, the uncertainty in momentum can be reduced by using a longer-wavelength electron, but this increases the uncertainty in position. Mathematically, you can express this trade-off by multiplying the uncertainties. The wavelength cancels, leaving

\[\Delta x \Delta p \approx h.\]

So if one uncertainty is reduced, the other must increase so that their product is \(\approx h\).

With the use of advanced mathematics, Heisenberg showed that the best that can be done in a simultaneous measurement of position and momentum is

\[\Delta x \Delta p \geq \dfrac{h}{4\pi}.\]

This is known as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. It is impossible to measure position \(x\) and momentum \(p\) simultaneously with uncertainties \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta p\) that multiply to be less than \(h/4\pi\). Neither uncertainty can be zero. Neither uncertainty can become small without the other becoming large. A small wavelength allows accurate position measurement, but it increases the momentum of the probe to the point that it further disturbs the momentum of a system being measured. For example, if an electron is scattered from an atom and has a wavelength small enough to detect the position of electrons in the atom, its momentum can knock the electrons from their orbits in a manner that loses information about their original motion. It is therefore impossible to follow an electron in its orbit around an atom. If you measure the electron’s position, you will find it in a definite location, but the atom will be disrupted. Repeated measurements on identical atoms will produce interesting probability distributions for electrons around the atom, but they will not produce motion information. The probability distributions are referred to as electron clouds or orbitals. The shapes of these orbitals are often shown in general chemistry texts and are discussed in The Wave Nature of Matter Causes Quantization.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle in Position and Momentum for an Atom

- If the position of an electron in an atom is measured to an accuracy of 0.0100 nm, what is the electron’s uncertainty in velocity?

- If the electron has this velocity, what is its kinetic energy in eV?

Strategy

The uncertainty in position is the accuracy of the measurement, or \(\Delta x = 0.0100 \, nm\). Thus the smallest uncertainty in momentum \(\Delta p\) can be calculated using \(\Delta x \Delta p \geq h/4\pi\). Once the uncertainty in momentum \(\Delta p\) is found, the uncertainty in velocity can be found from \(\Delta p = m\Delta v\).

Solution for (a)

Using the equals sign in the uncertainty principle to express the minimum uncertainty, we have

\[\Delta x \Delta p = \dfrac{h}{4\pi}.\]

Solving for \(\Delta p\) and substituting known values gives

\[p = \dfrac{h}{4\pi \Delta x} = \dfrac{6.63 \times 10^{-34} \, J \cdot}{4 \pi (1.00 \times 10^{-11} \, m)} = 5.28 \times 10^{-24} \, kg \cdot m/s\]

Thus,

\[\Delta p = 5.28 \times 10^{-24} \, kg \cdot m/s = m\Delta v.\]

Solving for \(\Delta v\) and substituting the mass of an electron gives

\[\Delta v = \dfrac{\Delta p}{m} = \dfrac{5.28 \times 10^{-24} \, kg \cdot m/s}{9.11 \times 10^{-31} \, kg} = 5.79 \times 10^6 \, m/s.\]

Solution for (b)

Although large, this velocity is not highly relativistic, and so the electron’s kinetic energy is

\[KE_e = \dfrac{1}{2} mv^2\]

\[= \dfrac{1}{2} (9.11 \times 10^{-31} \, kg)(5.79 \times 10^6 \, m/s)^2\]

\[= (1.53 \times 10^{-17} \, J)\left(\dfrac{1 \, eV}{1.60 \times 10^{-19} \, J}\right) = 95.5 \, eV.\]

Discussion

Since atoms are roughly 0.1 nm in size, knowing the position of an electron to 0.0100 nm localizes it reasonably well inside the atom. This would be like being able to see details one-tenth the size of the atom. But the consequent uncertainty in velocity is large. You certainly could not follow it very well if its velocity is so uncertain. To get a further idea of how large the uncertainty in velocity is, we assumed the velocity of the electron was equal to its uncertainty and found this gave a kinetic energy of 95.5 eV. This is significantly greater than the typical energy difference between levels in atoms (see [link]), so that it is impossible to get a meaningful energy for the electron if we know its position even moderately well.

Why don’t we notice Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in everyday life? The answer is that Planck’s constant is very small. Thus the lower limit in the uncertainty of measuring the position and momentum of large objects is negligible. We can detect sunlight reflected from Jupiter and follow the planet in its orbit around the Sun. The reflected sunlight alters the momentum of Jupiter and creates an uncertainty in its momentum, but this is totally negligible compared with Jupiter’s huge momentum. The correspondence principle tells us that the predictions of quantum mechanics become indistinguishable from classical physics for large objects, which is the case here.

Heisenberg Uncertainty for Energy and Time

There is another form of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle for simultaneous measurements of energy and time. In equation form,

\[\Delta E \Delta t \geq \dfrac{h}{4\pi},\]

where \(\Delta E\) is the uncertainty in energy and \(\Delta t\), is the uncertainty in time. This means that within a time interval \(\Delta t\), it is not possible to measure energy precisely—there will be an uncertainty \(\Delta E\) in the measurement. In order to measure energy more precisely (to make \(\Delta E\) smaller), we must increase \(\Delta t\). This time interval may be the amount of time we take to make the measurement, or it could be the amount of time a particular state exists, as in the next Example.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle for Energy and Time for an Atom

An atom in an excited state temporarily stores energy. If the lifetime of this excited state is measured to be \(1.0 \times 10^{-10} \, s\),

what is the minimum uncertainty in the energy of the state in eV?

Strategy

The minimum uncertainty in energy \(\Delta E\) is found by using the equals sign in \(\Delta E\Delta t \geq h/4\pi\) and corresponds to a reasonable choice for the uncertainty in time. The largest the uncertainty in time can be is the full lifetime of the excited state, or \(\Delta t = 1.0 \times 10^{-10} \, s\).

Solution

Solving the uncertainty principle for \(\Delta E\) and substituting known values gives

\[\Delta E = \dfrac{h}{4\pi \Delta t} = \dfrac{6.63 \times 10^{-34} \, J \cdot s}{4\pi (1.0 \times 10^{-10} \, s)} = 5.3 \times 10^{-25} \, J.\]

Now converting to eV yields

\[\Delta E = (5.3 \times 10^{-25} \, J) \left( \dfrac{1 \, eV}{1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, J} \right) = 3.3 \times 10^{-6} \, eV.\]

Discussion

The lifetime of \(10^{-10} \, s\) is typical of excited states in atoms—on human time scales, they quickly emit their stored energy. An uncertainty in energy of only a few millionths of an eV results. This uncertainty is small compared with typical excitation energies in atoms, which are on the order of 1 eV. So here the uncertainty principle limits the accuracy with which we can measure the lifetime and energy of such states, but not very significantly.

The uncertainty principle for energy and time can be of great significance if the lifetime of a system is very short. Then \(\Delta t\) is very small, and \(\Delta E\) is consequently very large. Some nuclei and exotic particles have extremely short lifetimes (as small as \(10^{-25} \, s\)), causing uncertainties in energy as great as many GeV \(10^9 \, eV\). Stored energy appears as increased rest mass, and so this means that there is significant uncertainty in the rest mass of short-lived particles. When measured repeatedly, a spread of masses or decay energies are obtained. The spread is \(\Delta E\). You might ask whether this uncertainty in energy could be avoided by not measuring the lifetime. The answer is no. Nature knows the lifetime, and so its brevity affects the energy of the particle. This is so well established experimentally that the uncertainty in decay energy is used to calculate the lifetime of short-lived states. Some nuclei and particles are so short-lived that it is difficult to measure their lifetime. But if their decay energy can be measured, its spread is \(\Delta E\) and this is used in the uncertainty principle \((\Delta E \Delta t \geq h/4\pi)\) to calculate the lifetime \(\Delta t\).

There is another consequence of the uncertainty principle for energy and time. If energy is uncertain by \(\Delta E\), then conservation of energy can be violated by \(\Delta E\) for a time \(\Delta t\). Neither the physicist nor nature can tell that conservation of energy has been violated, if the violation is temporary and smaller than the uncertainty in energy. While this sounds innocuous enough, we shall see in later chapters that it allows the temporary creation of matter from nothing and has implications for how nature transmits forces over very small distances.

Finally, note that in the discussion of particles and waves, we have stated that individual measurements produce precise or particle-like results. A definite position is determined each time we observe an electron, for example. But repeated measurements produce a spread in values consistent with wave characteristics. The great theoretical physicist Richard Feynman (1918–1988) commented, “What there are, are particles.” When you observe enough of them, they distribute themselves as you would expect for a wave phenomenon. However, what there are as they travel we cannot tell because, when we do try to measure, we affect the traveling.

Summary

- Matter is found to have the same interference characteristics as any other wave.

- There is now a probability distribution for the location of a particle rather than a definite position.

- Another consequence of the wave character of all particles is the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which limits the precision with which certain physical quantities can be known simultaneously. For position and momentum, the uncertainty principle is \(\Delta x \Delta p \geq \frac{h}{4 \pi}\), where \(\Delta x\) is the uncertainty in position and \(\Delta p\) is the uncertainty in momentum.

- For energy and time, the uncertainty principle is \(\Delta E \Delta t \geq \frac{h}{4 \pi}\), where \(\Delta E\) is the uncertainty in energy and \(\Delta t\) is the uncertainty in time.

- These small limits are fundamentally important on the quantum-mechanical scale.

Glossary

- Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle

- a fundamental limit to the precision with which pairs of quantities (momentum and position, and energy and time) can be measured

- uncertainty in energy

- lack of precision or lack of knowledge of precise results in measurements of energy

- uncertainty in time

- lack of precision or lack of knowledge of precise results in measurements of time

- uncertainty in momentum

- lack of precision or lack of knowledge of precise results in measurements of momentum

- uncertainty in position

- lack of precision or lack of knowledge of precise results in measurements of position

- probability distribution

- the overall spatial distribution of probabilities to find a particle at a given location