8.2: Impulse

- Page ID

- 1538

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define impulse.

- Describe effects of impulses in everyday life.

- Determine the average effective force using graphical representation.

- Calculate average force and impulse given mass, velocity, and time.

The effect of a force on an object depends on how long it acts, as well as how great the force is. In [link], a very large force acting for a short time had a great effect on the momentum of the tennis ball. A small force could cause the same change in momentum, but it would have to act for a much longer time. For example, if the ball were thrown upward, the gravitational force (which is much smaller than the tennis racquet’s force) would eventually reverse the momentum of the ball. Quantitatively, the effect we are talking about is the change in momentum \(\Delta p\).

By rearranging the equation \(\Delta F_{net} = \frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t} \) to be

\[\Delta p = F_{net} \Delta t,\]

we can see how the change in momentum equals the average net external force multiplied by the time this force acts. The quantity \(F_{net} \Delta t\) is given the name impulse. Impulse is the same as the change in momentum.

Impulse: Change in Momentum

Change in momentum equals the average net external force multiplied by the time this force acts.

\[\Delta p = F_{net} \Delta t\]

The quantity \( F_{net}\Delta t\) is given the name impulse.

There are many ways in which an understanding of impulse can save lives, or at least limbs. The dashboard padding in a car, and certainly the airbags, allow the net force on the occupants in the car to act over a much longer time when there is a sudden stop. The momentum change is the same for an occupant, whether an air bag is deployed or not, but the force (to bring the occupant to a stop) will be much less if it acts over a larger time. Cars today have many plastic components. One advantage of plastics is their lighter weight, which results in better gas mileage. Another advantage is that a car will crumple in a collision, especially in the event of a head-on collision. A longer collision time means the force on the car will be less. Deaths during car races decreased dramatically when the rigid frames of racing cars were replaced with parts that could crumple or collapse in the event of an accident.

Bones in a body will fracture if the force on them is too large. If you jump onto the floor from a table, the force on your legs can be immense if you land stiff-legged on a hard surface. Rolling on the ground after jumping from the table, or landing with a parachute, extends the time over which the force (on you from the ground) acts.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Magnitudes of Impulses: Two Billiard Balls Striking a Rigid Wall

Two identical billiard balls strike a rigid wall with the same speed, and are reflected without any change of speed. The first ball strikes perpendicular to the wall. The second ball strikes the wall at an angle of \(30^o\) from the perpendicular, and bounces off at an angle of \(30^o\) from perpendicular to the wall.

- Determine the direction of the force on the wall due to each ball.

- Calculate the ratio of the magnitudes of impulses on the two balls by the wall.

Strategy for (a)

In order to determine the force on the wall, consider the force on the ball due to the wall using Newton’s second law and then apply Newton’s third law to determine the direction. Assume the \(x-\)axis to be normal to the wall and to be positive in the initial direction of motion. Choose the \(y-\)axis to be along the wall in the plane of the second ball’s motion. The momentum direction and the velocity direction are the same.

Strategy for (a)

In order to determine the force on the wall, consider the force on the ball due to the wall using Newton’s second law and then apply Newton’s third law to determine the direction. Assume the \(x-\)axis to be normal to the wall and to be positive in the initial direction of motion. Choose the \(y-\)axis to be along the wall in the plane of the second ball’s motion. The momentum direction and the velocity direction are the same.

Solution for (a)

The first ball bounces directly into the wall and exerts a force on it in the +\(x\) direction. Therefore the wall exerts a force on the ball in the -\(y\) direction. The second ball continues with the same momentum component in the \(y-\) direction, but reverses its \(x\)-component of momentum, as seen by sketching a diagram of the angles involved and keeping in mind the proportionality between velocity and momentum.

These changes mean the change in momentum for both balls is in the \(-x\) direction, so the force of the wall on each ball is along the \(-x\) direction.

Strategy for (b)

Calculate the change in momentum for each ball, which is equal to the impulse imparted to the ball.

Solution for (b)

Let \(\mu\) be the speed of each ball before and after collision with the wall, and \(m\) the mass of each ball. Choose the \(x-\)axis and \(y-\)axis as previously described, and consider the change in momentum of the first ball which strikes perpendicular to the wall.

\[p_{xi} = m\mu; \, p_{yi} = 0\]

\[p_{xf} = -m\mu; \, p_{yf} = 0\]

Impulse is the change in momentum vector. Therefore the \(x-\)component of impulse is equal to -\(2m\mu\) and the \(y-\)component of impulse is equal to zero.

Now consider the change in momentum of the second ball.

\[p_{xi} = m/mu \, cos 30^o; \, p_{yi} = -m\mu \, 30^o\]

\[p_{xf} = -m/mu \, cos 30^o; \, p_{yf} = -m\mu \, 30^o\]

It should be noted here that while \(p_x\) changes sign after the collision, \(p_y\) does not. Therefore the -component of impulse is equal to \(-2m\mu \, cos \, 30^o\) and the \(y-\)component of impulse is equal to zero.

The ratio of the magnitudes of the impulse imparted to the balls is

\[ \dfrac{2m\mu}{2m\mu \, 30^o} = \dfrac{2}{sqrt{3}} = 1.155.\]

Discussion

The direction of impulse and force is the same as in the case of (a); it is normal to the wall and along the negative \(x-\)direction. Making use of Newton’s third law, the force on the wall due to each ball is normal to the wall along the positive \(x-\)direction.

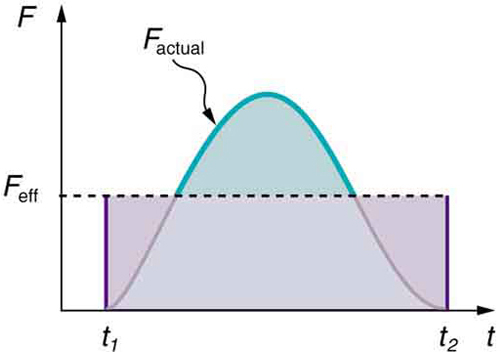

Our definition of impulse includes an assumption that the force is constant over the time interval \(\Delta t\).Forces are usually not constant. Forces vary considerably even during the brief time intervals considered. It is, however, possible to find an average effective force \(F_{eff}\) that produces the same result as the corresponding time-varying force. Figure shows a graph of what an actual force looks like as a function of time for a ball bouncing off the floor. The area under the curve has units of momentum and is equal to the impulse or change in momentum between times \(t_1\) and \(t_2\). That area is equal to the area inside the rectangle bounded by \(F_{eff}, \, t_1\), and \(t_2\) Thus the impulses and their effects are the same for both the actual and effective forces.

MAKING CONNECTIONS: Take-Home Investigation—Hand Movement and Impulse

Try catching a ball while “giving” with the ball, pulling your hands toward your body. Then, try catching a ball while keeping your hands still. Hit water in a tub with your full palm. After the water has settled, hit the water again by diving your hand with your fingers first into the water. (Your full palm represents a swimmer doing a belly flop and your diving hand represents a swimmer doing a dive.) Explain what happens in each case and why. Which orientations would you advise people to avoid and why?

MAKING CONNECTIONS: Constant Force anD Constant Acceleration

The assumption of a constant force in the definition of impulse is analogous to the assumption of a constant acceleration in kinematics. In both cases, nature is adequately described without the use of calculus.

Summary

- Impulse, or change in momentum, equals the average net external force multiplied by the time this force acts:

\[ \Delta p = F_{net}\Delta t.\]

- Forces are usually not constant over a period of time.

Glossary

- change in momentum

- the difference between the final and initial momentum; the mass times the change in velocity

- impulse

- the average net external force times the time it acts; equal to the change in momentum