04. Applying Newton's 2nd Law to a Spring-Mass System

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Applying Newton's Second Law to a Spring-Mass System

Since we did not analyze systems involving springs in the previous dynamics section, we should make up for that omission now.

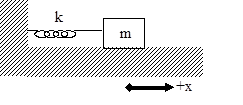

The system above consists of a spring with spring constant k attached to a block of mass m resting on a frictionless surface. The origin of the coordinate system is located at the position in which the spring is unstretched.

Now imagine the block is pulled to the right and let go. Hopefully you can convince yourself that the block will oscillate back and forth. Let's apply Newton's Second Law at the instant the mass is at an arbitrary position, x. The only force acting on the mass in the x-direction is the force of the spring.

∑→F=m→a

→Fspring=m→a

−ks=ma

Because of our choice of coordinate system, the stretch of the spring (s) is exactly equal to the location of the block (x). Therefore,

−kx=ma

Note that when the block is at a positibe position, the force of the spring is in the negative direction and when the block is at a negative positions, the force of the spring is in the positive direction. Thus, the force of the spring always acts to return the block to equilibrium.

Rearranging gives

and defining a constant, w2, as

(Granted, it seems pretty silly to define k/m as the square of a constant, but just play along. You may also find it frustrating to learn that this "omega" is not an angular velocity. The block does not even have an angular velocity!)

yields,

−ω2x=d2xdt2

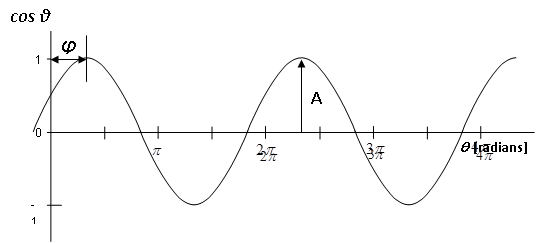

Therefore, the position function for the block must have a second time derivative equal to the product of (-w2) and itself. The only functions whose second time derivative is equal to the product of a negative constant and itself ar the sine and cosine functions. Therefore, a solution to this differential equation1 can be written:

x(t)=Acos(ωt+ϕ)

or equivalently with the sine function, where A and ϕ are arbitrary constants.2

- A is the amplitude of the oscillation. The amplitude is the maximum displacement of the object from equilibrium.

- ϕ is the phase angle. The phase angle is used to adjust the function forward or backward in time. For example, if the particle is at the origin at t = 0 s, ϕ must equal +π/2 or −π/2 to ensure that the cosine function evaluates to zero at t = 0 s. If the particle is at its maximum position at t = 0 s, then the phase angle must be zero or π to ensure that the cosine function evalutes to +1 or -1 at t = 0 s.

- ω is the angular frequency of the oscillation.3

Note that the cosine function repeats itself when its argument increases by \(2\pi\). Thus, when

- A differential equation is an equation involving a function and its derivative(s).

- To prove to yourself that this is indeed the solution to the equation, you should substitute the function, x(t), into the left side of the equation and the second derivative of x(t) into the right side. This will verify that the two sides of the equation are equal. In addition to mathematically verifying this solution, you should verify the solution physically by sketching a graph of the motion that youknow would result if the block were displaced to the right and comparing that sketch to a sketch of the function.

- Again, note that ωis not the angular velocity. The block is not rotating; it does not have an angular velocity.