3.3: Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) and his Laws of Planetary Motion

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Johannes Kepler Unidentified painter/Public domain;

Johannes Kepler Unidentified painter/Public domain; Johannes Kepler was born in Free Imperial City of Weil der Stadt, in what is now Stuttgart, Germany. Despite his early interest in astronomy, he contract smallpox as a child which left him with poor vision and weakened hands, limiting his ability to practice observational astronomy. He studied philosophy and theology at the University of Tubingen and became a teacher of mathematics at a grammar school in Graz. He impressed his fellow students with his skill in mathematics and astronomy by casting horoscopes for them (remember that, at this time, astronomy and astrology were considered one and the same). This led to an appointment as a professor of mathematics at the University of Tubingen. During this Kepler, also became a proponent of heliocentrism.

Religious and political difficulties eventually forced Kepler into exile from Graz. Not only did he refuse to convert to Catholicism, he also had to defend his mother from accusations of witchcraft. Fortunately, after some tense negotiations, he was able to secure a position in Prague as Tycho Brahe’s assistant in 1601. Kepler wanted access to Brahe’s collection of planetary data in order to work on the “Mars problem” that had set Copernicus on his course toward heliocentrism.

Fearing his new protégé might overshadow him, Tycho only shared a portion of his data with Kepler. Tycho assumed that this would keep his assistant busy. However, Tycho died shortly thereafter and Kepler inherited all of Tycho’s records. Using Tycho’s data, Kepler formulated his three laws of planetary motion.

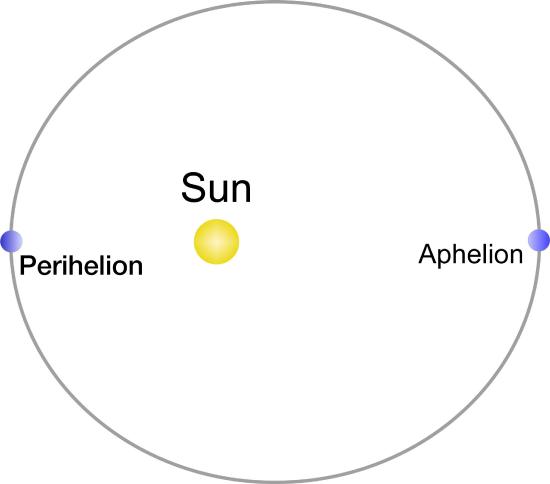

Kepler’s First Law: Planets orbit in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus.

Kepler's first law This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Austria license RJHall.

Kepler's first law This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Austria license RJHall.

Kepler’s replacement of the prefect circle with an ellipse was perhaps his most revolutionary idea, but it turned out to be mathematically and physically correct. Elliptical orbits solved the problem of both the Ptolemaic geocentric model and the Copernican heliocentric by making better predictions of planetary motion.

Kepler’s Second Law: An imaginary line connecting Sun and planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

Kepler's second law; This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Austria license RJHall.

Kepler's second law; This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Austria license RJHall.Because planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, their distance from the Sun changes. We call the point of closest approach to the Sun perihelion and the point of furthest distance from the Sun aphelion. Kepler’s Second Law shows that the orbital speed of a planet changes as it moves along its path. In order to cover equal areas in equal periods of times, the planet must travel its fastest during perihelion and slowest during aphelion.

Kepler’s Third Law: Square of period of planet’s orbital motion is proportional to cube of semimajor axis.

Kepler developed his third law empirically but crunching the numbers, but we can demonstrate that this relationship holds with all eight planets. Also, if we use AUs (length of Earth’s semimajor axis) as the unit for the planet’s semimajor axis (a) and Earth years as the unit for the planet’s orbital period (p), the relationship simplifies to:

a2 = p3.

Kepler’s third law, however, can only tell us the relative distances of planets from the Sun in AUs. We were unable to convert AUs into kilometers until we could use radar signals to measure the distance between Earth and Venus at their closest approach. Once we had that distance, we could describe the semimajor axes of all the planets in terrestrial units.