8.3: The Surface and Structure of the Moon.

- Page ID

- 30909

8.3.1 The Lunar Surface

The surface of the Moon consists of large dark flat areas, called maria (early observers thought they were oceans and thus gave them the Latin name for seas), due to lava flow. In addition to the maria, the Moon has numerous craters and mountain ranges. Compared to the near side of the Moon, the far side is more heavily cratered with fewer maria.

Craters form when a meteoroid strikes the Moon; explosion ejects material, leaving a crater. Craters are typically about 10 times as wide as the meteoroid creating them, and twice as deep. The impact pulverizes rock to a much greater depth. Most lunar craters date to at least 3.9 billion years ago, which is the period of the Late Heavy Bombardment. Since then, there has been much less bombardment since then. What bombardment the Moon receives is mostly from very small “micrometeoroids.” These tiny impacts slowly erode and soften features. Since the Moon lacks an atmosphere, it does not experience any erosion from wind or water as the Earth does. The surface of the Moon is also covered with regolith, a thick layer of dust left by meteorite impacts

Four billion years ago, the Moon had many craters but no maria. Heavy impacts on the near side produced lava flows from the Moon’s mantle covered portions of the Moon, creating the maria. By 3 billion years ago, Moon’s internal temperature had cooled to the point where no further lava flows occurred. Since then, many of the Maria have received occasional impacts, covering them in younger craters.

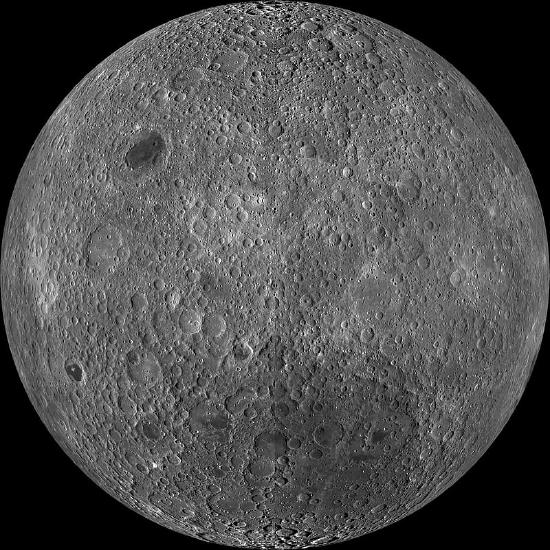

The far side of the Moon shows more impact craters compared to the near side.

The far side of the Moon shows more impact craters compared to the near side.

Craters near the poles of the Moon are in permanent shadow. Recent probes from NASA and India have found evidence of water ice inside these craters. Asteroids containing ice probably delivered this ice and since these craters receive no sunlight, the ice has never sublimated (turned from solid to vapor phase).

During the Moon’s early formation. the Earth’s gravity pulled more magma to the surface on the near side. This resulted in less magma welling up to the surface on the far side, so impacts just built up craters and mountains. This made the Moon’s crust thicker on the far side.

Apollo astronauts installed the first lunar seismic detectors to study the Moon’s interior. The instruments registered some meteorite impacts and a very few moonquakes, showing the Moon to be much less geologically active than the Earth. Using the sparse data, scientists found that the interior of the Moon is essentially the same material as the Earth's mantle, with perhaps a very small iron core. The Moon's lithosphere is about 1,000 kilometers deep — much thicker than the Earth's lithosphere. Because the Moon is smaller than the Earth, it cooled more quickly and completely, creating a relatively thicker lithosphere.

Based on radiometric dating of lunar rocks, astronomers divide the surface of the Moon into different periods:

Surfaces that formed during the Pre-Nectarian Period are between 4.5 to 3.9 Billion years in age. Rocks from the Nectarian Period run from 3.9 to 3.8 Billion years in age. The Imbrian Period consists of surfaces from 3.8 to 3.2 billion years in age. The Eratosthenian Period follows, from 3.2 to 1.1 billion years ago. Finally, the youngest surfaces date from the Copernican Period, with ages from 1.1 billion years ago until today.

Craters on the Moon formed mostly through impacts from meteoroids.

Craters on the Moon formed mostly through impacts from meteoroids.

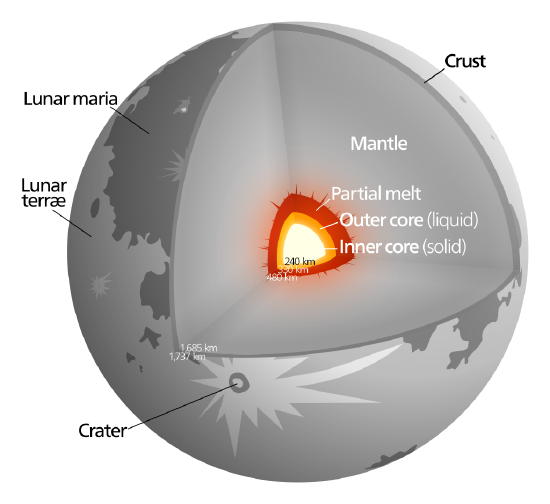

The Moon's internal structure

The Moon's internal structure

8.3.2 Origin of the Moon

Before we analyzed the composition of the moon rocks brought back by the Apollo missions, there were several theories about the origin of the Moon. The first was the fission theory, in which the Moon was once part of Earth, but somehow separated from it early in their history. The other theory was known as the sister theory, in which the Moon formed together with but independent of Earth, as we believe many moons of the outer planets formed. A third theory, the capture theory posited that the Moon formed elsewhere in the solar system and was captured by Earth.

However, analysis of the lunar rocks found that none of theories matched the data. Geologists found that the Moon is deficient in iron compared to the Earth and is made from material like the Earth's mantle. The lunar surface is also deficient in water and other volatile compounds, compared to the Earth. In short, the Moon was like the Earth in all the wrong ways as predicted by any of the previous theories. The proportions of different oxygen isotopes in lunar rocks (e.g. O16, O18, etc.) are the same as in terrestrial minerals, but different from those in other parts of the Solar System.

We know that very large bodies hit the Moon early in its history and even though the evidence is masked by erosion and geological upheaval, very large bodies also hit the Earth. The current theory of the Moon’s origin posits a Mars-sized body (Which astronomers have named Theia), impacted the still-liquid Earth with a glancing blow. This caused enough material, mostly from the mantle, to be ejected. This material remained in orbit around the Earth and eventually coalesced to form the Moon.

The Moon likely formed by an impact of the Earth by a Mars-sized object.

The Moon likely formed by an impact of the Earth by a Mars-sized object.