4.4: Newton’s Second Law of Motion- Concept of a System

- Last updated

- Jul 16, 2020

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 26503

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define net force, external force, and system.

- Understand Newton’s second law of motion.

- Apply Newton’s second law to determine the weight of an object.

Newton’s second law of motion is closely related to Newton’s first law of motion. It mathematically states the cause and effect relationship between force and changes in motion. Newton’s second law of motion is more quantitative and is used extensively to calculate what happens in situations involving a force. Before we can write down Newton’s second law as a simple equation giving the exact relationship of force, mass, and acceleration, we need to sharpen some ideas that have already been mentioned.

First, what do we mean by a change in motion? The answer is that a change in motion is equivalent to a change in velocity. A change in velocity means, by definition, that there is an acceleration. Newton’s first law says that a net external force causes a change in motion; thus, we see that a net external force causes acceleration.

Another question immediately arises. What do we mean by an external force? An intuitive notion of external is correct — an external force acts from outside the system of interest. For example, in Figure 4.4.1a the system of interest is the wagon plus the child in it. The two forces exerted by the other children are external forces. An internal force acts between elements of the system. Again looking at Figure 4.4.1a, the force the child in the wagon exerts to hang onto the wagon is an internal force between elements of the system of interest. Only external forces affect the motion of a system, according to Newton’s first law. (The internal forces actually cancel, as we shall see in the next section.) You must define the boundaries of the system before you can determine which forces are external. Sometimes the system is obvious, whereas other times identifying the boundaries of a system is more subtle. The concept of a system is fundamental to many areas of physics, as is the correct application of Newton’s laws. This concept will be revisited many times on our journey through physics.

Now, it seems reasonable that acceleration should be directly proportional to and in the same direction as the net (total) external force acting on a system. This assumption has been verified experimentally and is illustrated in Figure. In part (a), a smaller force causes a smaller acceleration than the larger force illustrated in part (c). For completeness, the vertical forces are also shown; they are assumed to cancel since there is no acceleration in the vertical direction. The vertical forces are the weight w and the support of the ground N, and the horizontal force f represents the force of friction. These will be discussed in more detail in later sections. For now, we will define friction as a force that opposes the motion past each other of objects that are touching. Figure 4.4.1b shows how vectors representing the external forces add together to produce a net force, Fnet.

To obtain an equation for Newton’s second law, we first write the relationship of acceleration and net external force as the proportionality

a∝Fnet

where the symbol ∝ means “proportional to,” and Fnet is the net external force. (The net external force is the vector sum of all external forces and can be determined graphically, using the head-to-tail method, or analytically, using components. The techniques are the same as for the addition of other vectors, and are covered in the chapter section on Two-Dimensional Kinematics.) This proportionality states what we have said in words—acceleration is directly proportional to the net external force. Once the system of interest is chosen, it is important to identify the external forces and ignore the internal ones. It is a tremendous simplification not to have to consider the numerous internal forces acting between objects within the system, such as muscular forces within the child’s body, let alone the myriad of forces between atoms in the objects, but by doing so, we can easily solve some very complex problems with only minimal error due to our simplification

Now, it also seems reasonable that acceleration should be inversely proportional to the mass of the system. In other words, the larger the mass (the inertia), the smaller the acceleration produced by a given force. And indeed, as illustrated in Figure, the same net external force applied to a car produces a much smaller acceleration than when applied to a basketball. The proportionality is written as

a∝1m,

where m is the mass of the system. Experiments have shown that acceleration is exactly inversely proportional to mass, just as it is exactly linearly proportional to the net external force.

It has been found that the acceleration of an object depends only on the net external force and the mass of the object. Combining the two proportionalities just given yields Newton's second law of motion.

Newton’s Second Law of Motion

The acceleration of a system is directly proportional to and in the same direction as the net external force acting on the system, and inversely proportional to its mass. In equation form, Newton’s second law of motion is

a=Fnetm

This is often written in the more familiar form

Fnet=ma.

When only the magnitude of force and acceleration are considered, this equation is simply

Fnet=ma.

Although these last two equations are really the same, the first gives more insight into what Newton’s second law means. The law is a cause and effect relationship among three quantities that is not simply based on their definitions. The validity of the second law is completely based on experimental verification.

Units of Force

Fnet=ma is used to define the units of force in terms of the three basic units for mass, length, and time. The SI unit of force is called the newton (abbreviated N) and is the force needed to accelerate a 1-kg system at the rate of 1m/s2 That is, since Fnet=ma, 1N=1kg⋅s2

While almost the entire world uses the newton for the unit of force, in the United States the most familiar unit of force is the pound (lb), where 1 N = 0.225 lb.

Weight and the Gravitational Force

When an object is dropped, it accelerates toward the center of Earth. Newton’s second law states that a net force on an object is responsible for its acceleration. If air resistance is negligible, the net force on a falling object is the gravitational force, commonly called its weight w. Weight can be denoted as a vector w because it has a direction; down is, by definition, the direction of gravity, and hence weight is a downward force. The magnitude of weight is denoted as w. Galileo was instrumental in showing that, in the absence of air resistance, all objects fall with the same acceleration w. Using Galileo’s result and Newton’s second law, we can derive an equation for weight.

Consider an object with mass m falling downward toward Earth. It experiences only the downward force of gravity, which has magnitude w. Newton’s second law states that the magnitude of the net external force on an object is Fnet=ma.

Since the object experiences only the downward force of gravity, Fnet=w. We know that the acceleration of an object due to gravity is g, or a=g. Substituting these into Newton’s second law gives

WEIGHT

This is the equation for weight - the gravitational force on mass m:

w=mg

Since weight g=9.80m/s2 on Earth, the weight of a 1.0 kg object on Earth is 9.8 N, as we see: w=mg=(1.0kg)(9.8m/s2)=9.8N.

Recall that g can take a positive or negative value, depending on the positive direction in the coordinate system. Be sure to take this into consideration when solving problems with weight.

When the net external force on an object is its weight, we say that it is in free-fall. That is, the only force acting on the object is the force of gravity. In the real world, when objects fall downward toward Earth, they are never truly in free-fall because there is always some upward force from the air acting on the object.

The acceleration due to gravity g varies slightly over the surface of Earth, so that the weight of an object depends on location and is not an intrinsic property of the object. Weight varies dramatically if one leaves Earth’s surface. On the Moon, for example, the acceleration due to gravity is only 1.67m/s2. A 1.0-kg mass thus has a weight of 9.8 N on Earth and only about 1.7 N on the Moon.

The broadest definition of weight in this sense is that the weight of an object is the gravitational force on it from the nearest large body, such as Earth, the Moon, the Sun, and so on. This is the most common and useful definition of weight in physics. It differs dramatically, however, from the definition of weight used by NASA and the popular media in relation to space travel and exploration. When they speak of “weightlessness” and “microgravity,” they are really referring to the phenomenon we call “free-fall” in physics. We shall use the above definition of weight, and we will make careful distinctions between free-fall and actual weightlessness.

It is important to be aware that weight and mass are very different physical quantities, although they are closely related. Mass is the quantity of matter (how much “stuff”) and does not vary in classical physics, whereas weight is the gravitational force and does vary depending on gravity. It is tempting to equate the two, since most of our examples take place on Earth, where the weight of an object only varies a little with the location of the object. Furthermore, the terms mass and weight are used interchangeably in everyday language; for example, our medical records often show our “weight” in kilograms, but never in the correct units of newtons.

COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS: MASS VS. WEIGHT

Mass and weight are often used interchangeably in everyday language. However, in science, these terms are distinctly different from one another. Mass is a measure of how much matter is in an object. The typical measure of mass is the kilogram (or the “slug” in English units). Weight, on the other hand, is a measure of the force of gravity acting on an object. Weight is equal to the mass of an object (m) multiplied by the acceleration due to gravity (g). Like any other force, weight is measured in terms of newtons (or pounds in English units).

Assuming the mass of an object is kept intact, it will remain the same, regardless of its location. However, because weight depends on the acceleration due to gravity, the weight of an object can change when the object enters into a region with stronger or weaker gravity. For example, the acceleration due to gravity on the Moon is 1.67m/s2 (which is much less than the acceleration due to gravity on Earth, 9.80m/s2 ). If you measured your weight on Earth and then measured your weight on the Moon, you would find that you “weigh” much less, even though you do not look any skinnier. This is because the force of gravity is weaker on the Moon. In fact, when people say that they are “losing weight,” they really mean that they are losing “mass” (which in turn causes them to weigh less)

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: MASS AND WEIGHT

What do bathroom scales measure? When you stand on a bathroom scale, what happens to the scale? It depresses slightly. The scale contains springs that compress in proportion to your weight—similar to rubber bands expanding when pulled. The springs provide a measure of your weight (for an object which is not accelerating). This is a force in newtons (or pounds). In most countries, the measurement is divided by 9.80 to give a reading in mass units of kilograms. The scale measures weight but is calibrated to provide information about mass. While standing on a bathroom scale, push down on a table next to you. What happens to the reading? Why? Would your scale measure the same “mass” on Earth as on the Moon?

Example 4.4.1:What Acceleration Can a Person Produce when pushing a Lawn Mower?

Suppose that the net external force (push minus friction) exerted on a lawn mower is 51 N (about 11 lb) parallel to the ground. The mass of the mower is 24 kg. What is its acceleration?

Strategy

Since Fnet and m are given, the acceleration can be calculated directly from Newton’s second law as stated in Fnet=ma.

Solution

The magnitude of the acceleration a is a=Fnetm. Entering known values gives a=51N24kg

Substituting the units kg⋅m/s2 for N yields a=51kg/s224 kg=2.1 m/s2

Discussion

The direction of the acceleration is the same direction as that of the net force, which is parallel to the ground. There is no information given in this example about the individual external forces acting on the system, but we can say something about their relative magnitudes. For example, the force exerted by the person pushing the mower must be greater than the friction opposing the motion (since we know the mower moves forward), and the vertical forces must cancel if there is to be no acceleration in the vertical direction (the mower is moving only horizontally). The acceleration found is small enough to be reasonable for a person pushing a mower. Such an effort would not last too long because the person’s top speed would soon be reached.

Example 4.4.2:What Rocket Thrust Accelerates This Sled?

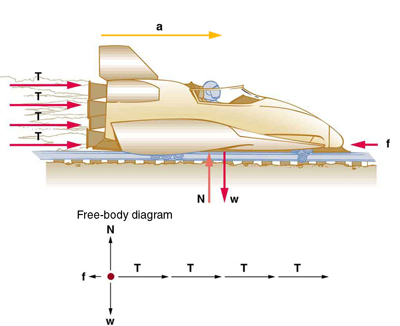

Prior to manned space flights, rocket sleds were used to test aircraft, missile equipment, and physiological effects on human subjects at high speeds. They consisted of a platform that was mounted on one or two rails and propelled by several rockets. Calculate the magnitude of force exerted by each rocket, called its thrust T for the four-rocket propulsion system shown in Figure. The sled’s initial acceleration is 49m/s2 the mass of the system is 2100 kg, and the force of friction opposing the motion is known to be 650 N.

Strategy

Although there are forces acting vertically and horizontally, we assume the vertical forces cancel since there is no vertical acceleration. This leaves us with only horizontal forces and a simpler one-dimensional problem. Directions are indicated with plus or minus signs, with right taken as the positive direction. See the free-body diagram in the figure.

Solution

Since acceleration, mass, and the force of friction are given, we start with Newton’s second law and look for ways to find the thrust of the engines. Since we have defined the direction of the force and acceleration as acting “to the right,” we need to consider only the magnitudes of these quantities in the calculations. Hence we begin with Fnet=ma., where Fnet is the net force along the horizontal direction. We can see from Figure that the engine thrusts add, while friction opposes the thrust. In equation form, the net external force is Fnet=4T−f.

Substituting this into Newton’s second law gives Fnet=ma=4T−f.

Using a little algebra, we solve for the total thrust 4T: 4T=ma+f.

Substituting known values yields 4T=ma+f=(2100kg)(49m/s2)+650N

So the total thrust is 1×105N,

and the individual thrusts are T=1×1054=2.6×104N

Discussion

The numbers are quite large, so the result might surprise you. Experiments such as this were performed in the early 1960s to test the limits of human endurance and the setup designed to protect human subjects in jet fighter emergency ejections. Speeds of 1000 km/h were obtained, with accelerations of 45 g-s. (Recall that g, the acceleration due gravity is 9.80m/s2. When we say that an acceleration is 45 g-s, it is 45×9.80m/s2, which is approximately 440m/s2 ). While living subjects are not used any more, land speeds of 10,000 km/h have been obtained with rocket sleds. In this example, as in the preceding one, the system of interest is obvious. We will see in later examples that choosing the system of interest is crucial—and the choice is not always obvious.

Newton’s second law of motion is more than a definition; it is a relationship among acceleration, force, and mass. It can help us make predictions. Each of those physical quantities can be defined independently, so the second law tells us something basic and universal about nature. The next section introduces the third and final law of motion.

Summary

- Acceleration, a, is defined as a change in velocity, meaning a change in its magnitude or direction, or both.

- An external force is one acting on a system from outside the system, as opposed to internal forces, which act between components within the system.

- Newton’s second law of motion states that the acceleration of a system is directly proportional to and in the same direction as the net external force acting on the system, and inversely proportional to its mass.

- In equation form, Newton’s second law of motion is a=Fnetm

- This is often written in the more familiar form: Fnet=ma.

- The weight w of an object is defined as the force of gravity acting on an object of mass m. The object experiences an acceleration due to gravity g: w=mg.

- If the only force acting on an object is due to gravity, the object is in free fall.

- Friction is a force that opposes the motion past each other of objects that are touching.