8.4: Life, Chemical Evolution, and Climate Change

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Outline the origins and subsequent diversity of life on Earth

- Explain the ways that life and geological activity have influenced the evolution of the atmosphere

- Describe the causes and effects of the atmospheric greenhouse effect and global warming

- Describe the impact of human activity on our planet’s atmosphere and ecology

As far as we know, Earth seems to be the only planet in the solar system with life. The origin and development of life are an important part of our planet’s story. Life arose early in Earth’s history, and living organisms have been interacting with their environment for billions of years. We recognize that life-forms have evolved to adapt to the environment on Earth, and we are now beginning to realize that Earth itself has been changed in important ways by the presence of living matter. The study of the coevolution of life and our planet is one of the subjects of the modern science of astrobiology.

The Origin of Life

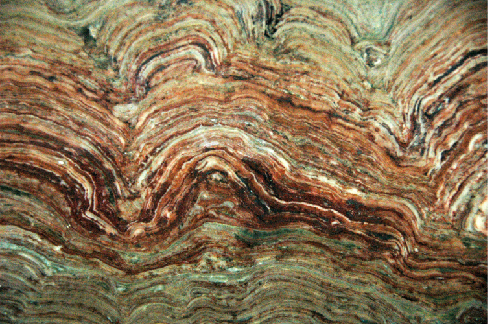

The record of the birth of life on Earth has been lost in the restless motions of the crust. According to chemical evidence, by the time the oldest surviving rocks were formed about 3.9 billion years ago, life already existed. At 3.5 billion years ago, life had achieved the sophistication to build large colonies called stromatolites, a form so successful that stromatolites still grow on Earth today (Figure 8.4.1). But, few rocks survive from these ancient times, and abundant fossils have been preserved only during the past 600 million years—less than 15% of our planet’s history.

There is little direct evidence about the actual origin of life. We know that the atmosphere of early Earth, unlike today’s, contained abundant carbon dioxide and some methane, but no oxygen gas. In the absence of oxygen, many complex chemical reactions are possible that lead to the production of amino acids, proteins, and other chemical building blocks of life. Therefore, it seems likely that these chemical building blocks were available very early in Earth’s history and they would have combined to make living organisms.

For tens of millions of years after Earth’s formation, life (perhaps little more than large molecules, like the viruses of today) probably existed in warm, nutrient-rich seas, living off accumulated organic chemicals. When this easily accessible food became depleted, life began the long evolutionary road that led to the vast numbers of different organisms on Earth today. As it did so, life began to influence the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

In addition to the study of life’s history as revealed by chemical and fossil evidence in ancient rocks, scientists use tools from the rapidly advancing fields of genetics and genomics—the study of the genetic code that is shared by all life on Earth. While each individual has a unique set of genes (which is why genetic “fingerprinting” is so useful for the study of crime), we also have many genetic traits in common. Your genome, the complete map of the DNA in your body, is identical at the 99.9% level to that of Julius Caesar or Marie Curie. At the 99% level, human and chimpanzee genomes are the same. By looking at the gene sequences of many organisms, we can determine that all life on Earth is descended from a common ancestor, and we can use the genetic variations among species as a measure of how closely different species are related.

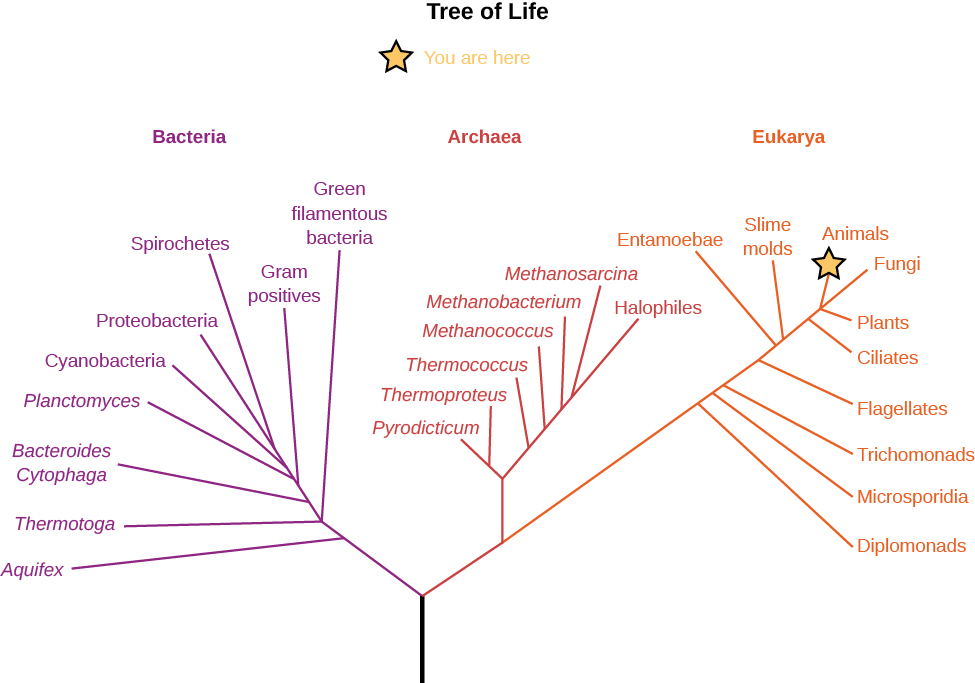

These genetic analysis tools have allowed scientists to construct what is called the “tree of life” (Figure 8.4.2). This diagram illustrates the way organisms are related by examining one sequence of the nucleic acid RNA that all species have in common. This figure shows that life on Earth is dominated by microscopic creatures that you have probably never heard of. Note that the plant and animal kingdoms are just two little branches at the far right. Most of the diversity of life, and most of our evolution, has taken place at the microbial level. Indeed, it may surprise you to know that there are more microbes in a bucket of soil than there are stars in the Galaxy. You may want to keep this in mind when, later in this book, we turn to the search for life on other worlds. The “aliens” that are most likely to be out there are microbes.

Such genetic studies lead to other interesting conclusions as well. For example, it appears that the earliest surviving terrestrial life-forms were all adapted to live at high temperatures. Some biologists think that life might actually have begun in locations on our planet that were extremely hot. Yet another intriguing possibility is that life began on Mars (which cooled sooner) rather than Earth and was “seeded” onto our planet by meteorites traveling from Mars to Earth. Mars rocks are still making their way to Earth, but so far none has shown evidence of serving as a “spaceship” to carry microorganisms from Mars to Earth.

The Evolution of the Atmosphere

One of the key steps in the evolution of life on Earth was the development of blue-green algae, a very successful life-form that takes in carbon dioxide from the environment and releases oxygen as a waste product. These successful microorganisms proliferated, giving rise to all the lifeforms we call plants. Since the energy for making new plant material from chemical building blocks comes from sunlight, we call the process photosynthesis.

Studies of the chemistry of ancient rocks show that Earth’s atmosphere lacked abundant free oxygen until about 2 billion years ago, despite the presence of plants releasing oxygen by photosynthesis. Apparently, chemical reactions with Earth’s crust removed the oxygen gas as quickly as it formed. Slowly, however, the increasing evolutionary sophistication of life led to a growth in the plant population and thus increased oxygen production. At the same time, it appears that increased geological activity led to heavy erosion on our planet’s surface. Tthis buried much of the plant carbon before it could recombine with oxygen to form CO2.

Free oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere about 2 billion years ago, and the increased amount of this gas led to the formation of Earth’s ozone layer (recall that ozone is a triple molecule of oxygen, O3), which protects the surface from deadly solar ultraviolet light. Before that, it was unthinkable for life to venture outside the protective oceans, so the landmasses of Earth were barren.

The presence of oxygen, and hence ozone, thus allowed colonization of the land. It also made possible a tremendous proliferation of animals, which lived by taking in and using the organic materials produced by plants as their own energy source.

As animals evolved in an environment increasingly rich in oxygen, they were able to develop techniques for breathing oxygen directly from the atmosphere. We humans take it for granted that plenty of free oxygen is available in Earth’s atmosphere, and we use it to release energy from the food we take in. Although it may seem funny to think of it this way, we are lifeforms that have evolved to breathe in the waste product of plants. It is plants and related microbes that are the primary producers, using sunlight to create energy-rich “food” for the rest of us.

On a planetary scale, one of the consequences of life has been a decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide. In the absence of life, Earth would probably have an atmosphere dominated by CO2, like Mars or Venus. But living things, in combination with high levels of geological activity, have effectively stripped our atmosphere of most of this gas.

The Greenhouse Effect and Global Warming

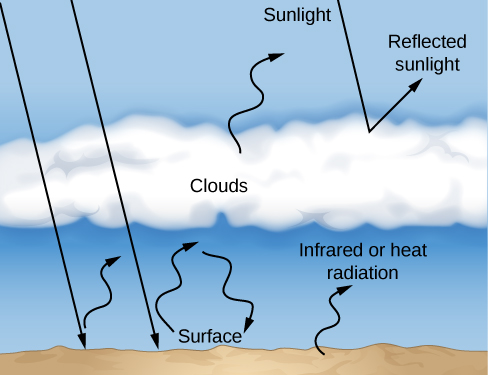

We have a special interest in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere because of the key role this gas plays in retaining heat from the Sun through a process called the greenhouse effect. To understand how the greenhouse effect works, consider the fate of sunlight that strikes the surface of Earth. The light penetrates our atmosphere, is absorbed by the ground, and heats the surface layers. At the temperature of Earth’s surface, that energy is then reemitted as infrared or heat radiation (Figure 8.4.3). However, the molecules of our atmosphere, which allow visible light through, are good at absorbing infrared energy. As a result, CO2 (along with methane and water vapor) acts like a blanket, trapping heat in the atmosphere and impeding its flow back to space. To maintain an energy balance, the temperature of the surface and lower atmosphere must increase until the total energy radiated by Earth to space equals the energy received from the Sun. The more CO2 there is in our atmosphere, the higher the temperature at which Earth’s surface reaches a new balance.

The greenhouse effect in a planetary atmosphere is similar to the heating of a gardener’s greenhouse or the inside of a car left out in the Sun with the windows rolled up. In these examples, the window glass plays the role of greenhouse gases, letting sunlight in but reducing the outward flow of heat radiation. As a result, a greenhouse or car interior winds up much hotter than would be expected from the heating of sunlight alone. On Earth, the current greenhouse effect elevates the surface temperature by about 23 °C. Without this greenhouse effect, the average surface temperature would be well below freezing and Earth would be locked in a global ice age.

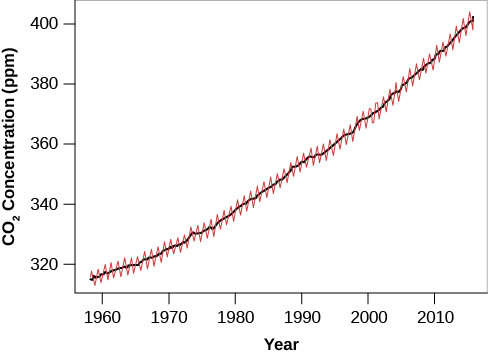

That’s the good news; the bad news is that the heating due to the greenhouse effect is increasing. Modern industrial society depends on energy extracted from burning fossil fuels. In effect, we are exploiting the energy-rich material created by photosynthesis tens of millions of years ago. As these ancient coal and oil deposits are oxidized (burned using oxygen), large quantities of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. The problem is exacerbated by the widespread destruction of tropical forests, which we depend on to extract CO2 from the atmosphere and replenish our supply of oxygen. In the past century of increased industrial and agricultural development, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere increased by about 30% and continues to rise at more than 0.5% per year.

Before the end of the present century, Earth’s CO2 level is predicted to reach twice the value it had before the industrial revolution (Figure 8.4.4). The consequences of such an increase for Earth’s surface and atmosphere (and the creatures who live there) are likely to be complex changes in climate, and may be catastrophic for many species. Many groups of scientists are now studying the effects of such global warming with elaborate computer models, and climate change has emerged as the greatest known threat (barring nuclear war) to both industrial civilization and the ecology of our planet.

This short PBS video explains the physics of the greenhouse effect.

Already climate change is widely apparent. Around the world, temperature records are constantly set and broken; all but one of the hottest recorded years have taken place since 2000. Glaciers are retreating, and the Arctic Sea ice is now much thinner than when it was first explored with nuclear submarines in the 1950s. Rising sea levels (from both melting glaciers and expansion of the water as its temperature rises) pose one of the most immediate threats, and many coastal cities have plans to build dikes or seawalls to hold back the expected flooding. The rate of temperature increase is without historical precedent, and we are rapidly entering “unknown territory” where human activities are leading to the highest temperatures on Earth in more than 50 million years.

Human Impacts on Our Planet

Earth is so large and has been here for so long that some people have trouble accepting that humans are really changing the planet, its atmosphere, and its climate. They are surprised to learn, for example, that the carbon dioxide released from burning fossil fuels is 100 times greater than that emitted by volcanoes. But, the data clearly tell the story that our climate is changing rapidly, and that almost all of the change is a result of human activity.

This is not the first time that humans have altered our environment dramatically. Some of the greatest changes were caused by our ancestors, before the development of modern industrial society. If aliens had visited Earth 50,000 years ago, they would have seen much of the planet supporting large animals of the sort that now survive only in Africa. The plains of Australia were occupied by giant marsupials such as diprododon and zygomaturus (the size of our elephants today), and a species of kangaroo that stood 10 feet high. North America and North Asia hosted mammoths, saber tooth cats, mastodons, giant sloths, and even camels. The Islands of the Pacific teemed with large birds, and vast forests covered what are now the farms of Europe and China. Early human hunters killed many large mammals and marsupials, early farmers cut down most of the forests, and the Polynesian expansion across the Pacific doomed the population of large birds.

An even greater mass extinction is underway as a result of rapid climate change. In recognition of our impact on the environment, scientists have proposed giving a new name to the current epoch, the anthropocine, when human activity started to have a significant global impact. Although not an officially approved name, the concept of “anthropocine” is useful for recognizing that we humans now represent the dominant influence on our planet’s atmosphere and ecology, for better or for worse.

Key Concepts and Summary

Life originated on Earth at a time when the atmosphere lacked O2 and consisted mostly of CO2. Later, photosynthesis gave rise to free oxygen and ozone. Modern genomic analysis lets us see how the wide diversity of species on the planet are related to each other. CO2 and methane in the atmosphere heat the surface through the greenhouse effect; today, increasing amounts of atmospheric CO2 are leading to the global warming of our planet.

Glossary

- greenhouse gas

- a gas in an atmosphere that absorbs and emits radiation within the thermal infrared range; on Earth, these atmospheric gases primarily include carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor

- greenhouse effect

- the blanketing (absorption) of infrared radiation near the surface of a planet—for example, by CO2 in its atmosphere

- photosynthesis

- a complex sequence of chemical reactions through which some living things can use sunlight to manufacture products that store energy (such as carbohydrates), releasing oxygen as one by-product