14.3: Formation of the Solar System

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the motion, chemical, and age constraints that must be met by any theory of solar system formation

- Summarize the physical and chemical changes during the solar nebula stage of solar system formation

- Explain the formation process of the terrestrial and giant planets

- Describe the main events of the further evolution of the solar system

As we have seen, the comets, asteroids, and meteorites are surviving remnants from the processes that formed the solar system. The planets, moons, and the Sun, of course, also are the products of the formation process, although the material in them has undergone a wide range of changes. We are now ready to put together the information from all these objects to discuss what is known about the origin of the solar system.

Observational Constraints

There are certain basic properties of the planetary system that any theory of its formation must explain. These may be summarized under three categories: motion constraints, chemical constraints, and age constraints. We call them constraints because they place restrictions on our theories; unless a theory can explain the observed facts, it will not survive in the competitive marketplace of ideas that characterizes the endeavor of science. Let’s take a look at these constraints one by one.

There are many regularities to the motions in the solar system. We saw that the planets all revolve around the Sun in the same direction and approximately in the plane of the Sun’s own rotation. In addition, most of the planets rotate in the same direction as they revolve, and most of the moons also move in counterclockwise orbits (when seen from the north). With the exception of the comets and other trans-neptunian objects, the motions of the system members define a disk or Frisbee shape. Nevertheless, a full theory must also be prepared to deal with the exceptions to these trends, such as the retrograde rotation (not revolution) of Venus.

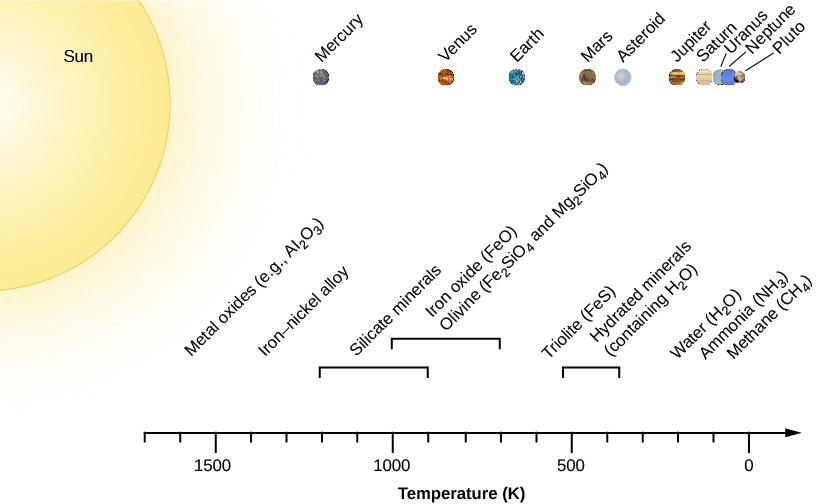

In the realm of chemistry, we saw that Jupiter and Saturn have approximately the same composition—dominated by hydrogen and helium. These are the two largest planets, with sufficient gravity to hold on to any gas present when and where they formed; thus, we might expect them to be representative of the original material out of which the solar system formed. Each of the other members of the planetary system is, to some degree, lacking in the light elements. A careful examination of the composition of solid solar-system objects shows a striking progression from the metal-rich inner planets, through those made predominantly of rocky materials, out to objects with ice-dominated compositions in the outer solar system. The comets in the Oort cloud and the trans-neptunian objects in the Kuiper belt are also icy objects, whereas the asteroids represent a transitional rocky composition with abundant dark, carbon-rich material.

As we saw in Other Worlds: An Introduction to the Solar System, this general chemical pattern can be interpreted as a temperature sequence: hot near the Sun and cooler as we move outward. The inner parts of the system are generally missing those materials that could not condense (form a solid) at the high temperatures found near the Sun. However, there are (again) important exceptions to the general pattern. For example, it is difficult to explain the presence of water on Earth and Mars if these planets formed in a region where the temperature was too hot for ice to condense, unless the ice or water was brought in later from cooler regions. The extreme example is the observation that there are polar deposits of ice on both Mercury and the Moon; these are almost certainly formed and maintained by occasional comet impacts.

As far as age is concerned, we discussed that radioactive dating demonstrates that some rocks on the surface of Earth have been present for at least 3.8 billion years, and that certain lunar samples are 4.4 billion years old. The primitive meteorites all have radioactive ages near 4.5 billion years. The age of these unaltered building blocks is considered the age of the planetary system. The similarity of the measured ages tells us that planets formed and their crusts cooled within a few tens of millions of years (at most) of the beginning of the solar system. Further, detailed examination of primitive meteorites indicates that they are made primarily from material that condensed or coagulated out of a hot gas; few identifiable fragments appear to have survived from before this hot-vapor stage 4.5 billion years ago.

The Solar Nebula

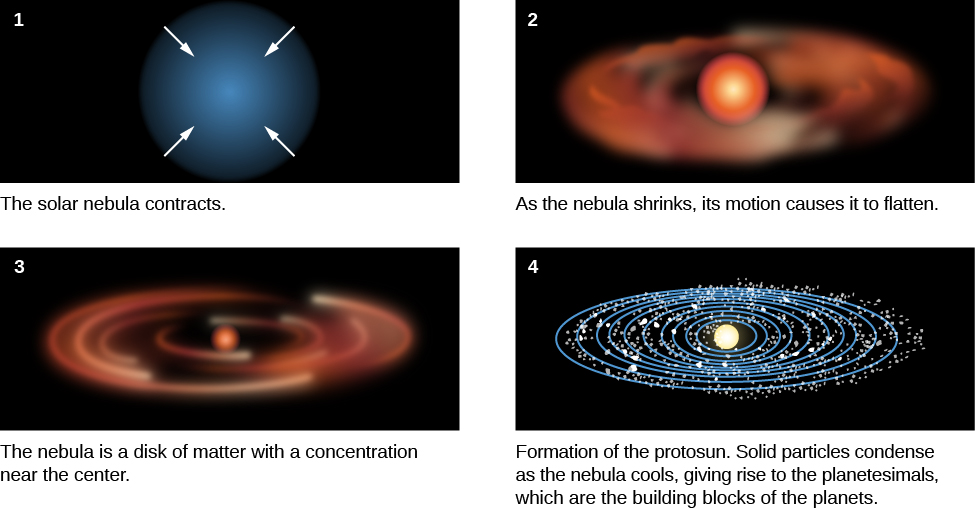

All the foregoing constraints are consistent with the general idea, introduced in Other Worlds: An Introduction to the Solar System, that the solar system formed 4.5 billion years ago out of a rotating cloud of vapor and dust—which we call the solar nebula—with an initial composition similar to that of the Sun today. As the solar nebula collapsed under its own gravity, material fell toward the center, where things became more and more concentrated and hot. Increasing temperatures in the shrinking nebula vaporized most of the solid material that was originally present.

At the same time, the collapsing nebula began to rotate faster through the conservation of angular momentum (see the Orbits and Gravity and Earth, Moon, and Sky chapters). Like a figure skater pulling her arms in to spin faster, the shrinking cloud spun more quickly as time went on. Now, think about how a round object spins. Close to the poles, the spin rate is slow, and it gets faster as you get closer to the equator. In the same way, near the poles of the nebula, where orbits were slow, the nebular material fell directly into the center. Faster moving material, on the other hand, collapsed into a flat disk revolving around the central object (Figure 14.3.1). The existence of this disk-shaped rotating nebula explains the primary motions in the solar system that we discussed in the previous section. And since they formed from a rotating disk, the planets all orbit the same way.

Picture the solar nebula at the end of the collapse phase, when it was at its hottest. With no more gravitational energy (from material falling in) to heat it, most of the nebula began to cool. The material in the center, however, where it was hottest and most crowded, formed a star that maintained high temperatures in its immediate neighborhood by producing its own energy. Turbulent motions and magnetic fields within the disk can drain away angular momentum, robbing the disk material of some of its spin. This allowed some material to continue to fall into the growing star, while the rest of the disk gradually stabilized.

The temperature within the disk decreased with increasing distance from the Sun, much as the planets’ temperatures vary with position today. As the disk cooled, the gases interacted chemically to produce compounds; eventually these compounds condensed into liquid droplets or solid grains. This is similar to the process by which raindrops on Earth condense from moist air as it rises over a mountain.

Let’s look in more detail at how material condensed at different places in the maturing disk (Figure 14.3.2). The first materials to form solid grains were the metals and various rock-forming silicates. As the temperature dropped, these were joined throughout much of the solar nebula by sulfur compounds and by carbon- and water-rich silicates, such as those now found abundantly among the asteroids. However, in the inner parts of the disk, the temperature never dropped low enough for such materials as ice or carbonaceous organic compounds to condense, so they were lacking on the innermost planets.

Far from the Sun, cooler temperatures allowed the oxygen to combine with hydrogen and condense in the form of water (H2O) ice. Beyond the orbit of Saturn, carbon and nitrogen combined with hydrogen to make ices such as methane (CH4) and ammonia (NH3). This sequence of events explains the basic chemical composition differences among various regions of the solar system.

Example 14.3.1: rotation of the solar nebula

We can use the concept of angular momentum to trace the evolution of the collapsing solar nebula. The angular momentum of an object is proportional to the square of its size (diameter) divided by its period of rotation (D2/P). If angular momentum is conserved, then any change in the size of a nebula must be compensated for by a proportional change in period, in order to keep D2/P constant. Suppose the solar nebula began with a diameter of 10,000 AU and a rotation period of 1 million years. What is its rotation period when it has shrunk to the size of Pluto’s orbit, which Appendix F tells us has a radius of about 40 AU?

Solution

We are given that the final diameter of the solar nebula is about 80 AU. Noting the initial state before the collapse and the final state at Pluto’s orbit, then

PfinalPinitial=(DfinalDinitial)2=(8010,000)2=(0.008)2=0.000064

With Pinitial equal to 1,000,000 years, Pfinal, the new rotation period, is 64 years. This is a lot shorter than the actual time Pluto takes to go around the Sun, but it gives you a sense of the kind of speeding up the conservation of angular momentum can produce. As we noted earlier, other mechanisms helped the material in the disk lose angular momentum before the planets fully formed.

Exercise 14.3.1

What would the rotation period of the nebula in our example be when it had shrunk to the size of Jupiter’s orbit?

- Answer

-

The period of the rotating nebula is inversely proportional to D2. As we have just seen, PfinalPinitial=(DfinalDinitial)2. Initially, we have Pinitial=106yrand\(Dinitial = 104 AU. Then, if Dfinal is in AU, Pfinal (in years) is given by Pfinal=0.01D2final. If Jupiter’s orbit has a radius of 5.2 AU, then the diameter is 10.4 AU. The period is then 1.08 years.

Formation of the Terrestrial Planets

The grains that condensed in the solar nebula rather quickly joined into larger and larger chunks, until most of the solid material was in the form of planetesimals, chunks a few kilometers to a few tens of kilometers in diameter. Some planetesimals still survive today as comets and asteroids. Others have left their imprint on the cratered surfaces of many of the worlds we studied in earlier chapters. A substantial step up in size is required, however, to go from planetesimal to planet.

Some planetesimals were large enough to attract their neighbors gravitationally and thus to grow by the process called accretion. While the intermediate steps are not well understood, ultimately several dozen centers of accretion seem to have grown in the inner solar system. Each of these attracted surrounding planetesimals until it had acquired a mass similar to that of Mercury or Mars. At this stage, we may think of these objects as protoplanets—“not quite ready for prime time” planets.

Each of these protoplanets continued to grow by the accretion of planetesimals. Every incoming planetesimal was accelerated by the gravity of the protoplanet, striking with enough energy to melt both the projectile and a part of the impact area. Soon the entire protoplanet was heated to above the melting temperature of rocks. The result was planetary differentiation, with heavier metals sinking toward the core and lighter silicates rising toward the surface. As they were heated, the inner protoplanets lost some of their more volatile constituents (the lighter gases), leaving more of the heavier elements and compounds behind.

Formation of the Giant Planets

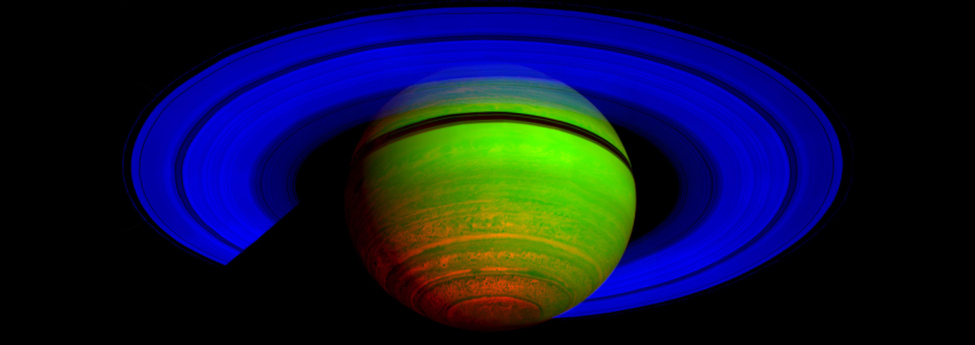

In the outer solar system, where the available raw materials included ices as well as rocks, the protoplanets grew to be much larger, with masses ten times greater than Earth. These protoplanets of the outer solar system were so large that they were able to attract and hold the surrounding gas. As the hydrogen and helium rapidly collapsed onto their cores, the giant planets were heated by the energy of contraction. But although these giant planets got hotter than their terrestrial siblings, they were far too small to raise their central temperatures and pressures to the point where nuclear reactions could begin (and it is such reactions that give us our definition of a star). After glowing dull red for a few thousand years, the giant planets gradually cooled to their present state (Figure 14.3.3).

The collapse of gas from the nebula onto the cores of the giant planets explains how these objects acquired nearly the same hydrogen-rich composition as the Sun. The process was most efficient for Jupiter and Saturn; hence, their compositions are most nearly “cosmic.” Much less gas was captured by Uranus and Neptune, which is why these two planets have compositions dominated by the icy and rocky building blocks that made up their large cores rather than by hydrogen and helium. The initial formation period ended when much of the available raw material was used up and the solar wind (the flow of atomic particles) from the young Sun blew away the remaining supply of lighter gases.

Further Evolution of the System

All the processes we have just described, from the collapse of the solar nebula to the formation of protoplanets, took place within a few million years. However, the story of the formation of the solar system was not complete at this stage; there were many planetesimals and other debris that did not initially accumulate to form the planets. What was their fate?

The comets visible to us today are merely the tip of the cosmic iceberg (if you’ll pardon the pun). Most comets are believed to be in the Oort cloud, far from the region of the planets. Additional comets and icy dwarf planets are in the Kuiper belt, which stretches beyond the orbit of Neptune. These icy pieces probably formed near the present orbits of Uranus and Neptune but were ejected from their initial orbits by the gravitational influence of the giant planets.

In the inner parts of the system, remnant planetesimals and perhaps several dozen protoplanets continued to whiz about. Over the vast span of time we are discussing, collisions among these objects were inevitable. Giant impacts at this stage probably stripped Mercury of part of its mantle and crust, reversed the rotation of Venus, and broke off part of Earth to create the Moon (all events we discussed in other chapters).

Smaller-scale impacts also added mass to the inner protoplanets. Because the gravity of the giant planets could “stir up” the orbits of the planetesimals, the material impacting on the inner protoplanets could have come from almost anywhere within the solar system. In contrast to the previous stage of accretion, therefore, this new material did not represent just a narrow range of compositions.

As a result, much of the debris striking the inner planets was ice-rich material that had condensed in the outer part of the solar nebula. As this comet-like bombardment progressed, Earth accumulated the water and various organic compounds that would later be critical to the formation of life. Mars and Venus probably also acquired abundant water and organic materials from the same source, as Mercury and the Moon are still doing to form their icy polar caps.

Gradually, as the planets swept up or ejected the remaining debris, most of the planetesimals disappeared. In two regions, however, stable orbits are possible where leftover planetesimals could avoid impacting the planets or being ejected from the system. These regions are the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and the Kuiper belt beyond Neptune. The planetesimals (and their fragments) that survive in these special locations are what we now call asteroids, comets, and trans-neptunian objects.

Astronomers used to think that the solar system that emerged from this early evolution was similar to what we see today. Detailed recent studies of the orbits of the planets and asteroids, however, suggest that there were more violent events soon afterward, perhaps involving substantial changes in the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. These two giant planets control, through their gravity, the distribution of asteroids. Working backward from our present solar system, it appears that orbital changes took place during the first few hundred million years. One consequence may have been scattering of asteroids into the inner solar system, causing the period of “heavy bombardment” recorded in the oldest lunar craters.

Key Concepts and Summary

A viable theory of solar system formation must take into account motion constraints, chemical constraints, and age constraints. Meteorites, comets, and asteroids are survivors of the solar nebula out of which the solar system formed. This nebula was the result of the collapse of an interstellar cloud of gas and dust, which contracted (conserving its angular momentum) to form our star, the Sun, surrounded by a thin, spinning disk of dust and vapor. Condensation in the disk led to the formation of planetesimals, which became the building blocks of the planets. Accretion of infalling materials heated the planets, leading to their differentiation. The giant planets were also able to attract and hold gas from the solar nebula. After a few million years of violent impacts, most of the debris was swept up or ejected, leaving only the asteroids and cometary remnants surviving to the present.

Glossary

- accretion

- the gradual accumulation of mass, as by a planet forming from colliding particles in the solar nebula