22.1: Evolution from the Main Sequence to Red Giants

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the zero-age main sequence

- Describe what happens to main-sequence stars of various masses as they exhaust their hydrogen supply

One of the best ways to get a “snapshot” of a group of stars is by plotting their properties on an H–R diagram. We have already used the H–R diagram to follow the evolution of protostars up to the time they reach the main sequence. Now we’ll see what happens next.

Once a star has reached the main-sequence stage of its life, it derives its energy almost entirely from the conversion of hydrogen to helium via the process of nuclear fusion in its core (see The Sun: A Nuclear Powerhouse). Since hydrogen is the most abundant element in stars, this process can maintain the star’s equilibrium for a long time. Thus, all stars remain on the main sequence for most of their lives. Some astronomers like to call the main-sequence phase the star’s “prolonged adolescence” or “adulthood” (continuing our analogy to the stages in a human life).

The left-hand edge of the main-sequence band in the H–R diagram is called the zero-age main sequence (see Figure 18.4.1 in Section 18.4). We use the term zero-age to mark the time when a star stops contracting, settles onto the main sequence, and begins to fuse hydrogen in its core. The zero-age main sequence is a continuous line in the H–R diagram that shows where stars of different masses but similar chemical composition can be found when they begin to fuse hydrogen.

Since only 0.7% of the hydrogen used in fusion reactions is converted into energy, fusion does not change the total mass of the star appreciably during this long period. It does, however, change the chemical composition in its central regions where nuclear reactions occur: hydrogen is gradually depleted, and helium accumulates. This change of composition changes the luminosity, temperature, size, and interior structure of the star. When a star’s luminosity and temperature begin to change, the point that represents the star on the H–R diagram moves away from the zero-age main sequence.

Calculations show that the temperature and density in the inner region slowly increase as helium accumulates in the center of a star. As the temperature gets hotter, each proton acquires more energy of motion on average; this means it is more likely to interact with other protons, and as a result, the rate of fusion also increases. For the proton-proton cycle described in The Sun: A Nuclear Powerhouse, the rate of fusion goes up roughly as the temperature to the fourth power.

If the rate of fusion goes up, the rate at which energy is being generated also increases, and the luminosity of the star gradually rises. Initially, however, these changes are small, and stars remain within the main-sequence band on the H–R diagram for most of their lifetimes.

Example 22.1.1: Star Temperature and Rate of Fusion

If a star’s temperature were to double, by what factor would its rate of fusion increase?

Solution

Since the rate of fusion (like temperature) goes up to the fourth power, it would increase by a factor of 24, or 16 times.

Exercise 22.1.1

If the rate of fusion of a star increased 256 times, by what factor would the temperature increase?

- Answer

-

The temperature would increase by a factor of 2560.25 (that is, the 4th root of 256), or 4 times.

Lifetimes on the Main Sequence

How many years a star remains in the main-sequence band depends on its mass. You might think that a more massive star, having more fuel, would last longer, but it’s not that simple. The lifetime of a star in a particular stage of evolution depends on how much nuclear fuel it has and on how quickly it uses up that fuel. (In the same way, how long people can keep spending money depends not only on how much money they have but also on how quickly they spend it. This is why many lottery winners who go on spending sprees quickly wind up poor again.) In the case of stars, more massive ones use up their fuel much more quickly than stars of low mass.

The reason massive stars are such spendthrifts is that, as we saw above, the rate of fusion depends very strongly on the star’s core temperature. And what determines how hot a star’s central regions get? It is the mass of the star—the weight of the overlying layers determines how high the pressure in the core must be: higher mass requires higher pressure to balance it. Higher pressure, in turn, is produced by higher temperature. The higher the temperature in the central regions, the faster the star races through its storehouse of central hydrogen. Although massive stars have more fuel, they burn it so prodigiously that their lifetimes are much shorter than those of their low-mass counterparts. You can also understand now why the most massive main-sequence stars are also the most luminous. Like new rock stars with their first platinum album, they spend their resources at an astounding rate.

The main-sequence lifetimes of stars of different masses are listed in Table 22.1.1. This table shows that the most massive stars spend only a few million years on the main sequence. A star of 1 solar mass remains there for roughly 10 billion years, while a star of about 0.4 solar mass has a main-sequence lifetime of some 200 billion years, which is longer than the current age of the universe. (Bear in mind, however, that every star spends most of its total lifetime on the main sequence. Stars devote an average of 90% of their lives to peacefully fusing hydrogen into helium.)

| Spectral Type | Surface Temperature (K) | Mass (Mass of Sun = 1) | Lifetime on Main Sequence (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O5 | 54,000 | 40 | 1 million |

| B0 | 29,200 | 16 | 10 million |

| A0 | 9600 | 3.3 | 500 million |

| F0 | 7350 | 1.7 | 2.7 billion |

| G0 | 6050 | 1.1 | 9 billion |

| K0 | 5240 | 0.8 | 14 billion |

| M0 | 3750 | 0.4 | 200 billion |

These results are not merely of academic interest. Human beings developed on a planet around a G-type star. This means that the Sun’s stable main-sequence lifetime is so long that it afforded life on Earth plenty of time to evolve. When searching for intelligent life like our own on planets around other stars, it would be a pretty big waste of time to search around O- or B-type stars. These stars remain stable for such a short time that the development of creatures complicated enough to take astronomy courses is very unlikely.

From Main-Sequence Star to Red Giant

Eventually, all the hydrogen in a star’s core, where it is hot enough for fusion reactions, is used up. The core then contains only helium, “contaminated” by whatever small percentage of heavier elements the star had to begin with. The helium in the core can be thought of as the accumulated “ash” from the nuclear “burning” of hydrogen during the main-sequence stage.

Energy can no longer be generated by hydrogen fusion in the stellar core because the hydrogen is all gone and, as we will see, the fusion of helium requires much higher temperatures. Since the central temperature is not yet high enough to fuse helium, there is no nuclear energy source to supply heat to the central region of the star. The long period of stability now ends, gravity again takes over, and the core begins to contract. Once more, the star’s energy is partially supplied by gravitational energy, in the way described by Kelvin and Helmholtz (see Sources of Sunshine: Thermal and Gravitational Energy). As the star’s core shrinks, the energy of the inward-falling material is converted to heat.

The heat generated in this way, like all heat, flows outward to where it is a bit cooler. In the process, the heat raises the temperature of a layer of hydrogen that spent the whole long main-sequence time just outside the core. Like an understudy waiting in the wings of a hit Broadway show for a chance at fame and glory, this hydrogen was almost (but not quite) hot enough to undergo fusion and take part in the main action that sustains the star. Now, the additional heat produced by the shrinking core puts this hydrogen “over the limit,” and a shell of hydrogen nuclei just outside the core becomes hot enough for hydrogen fusion to begin.

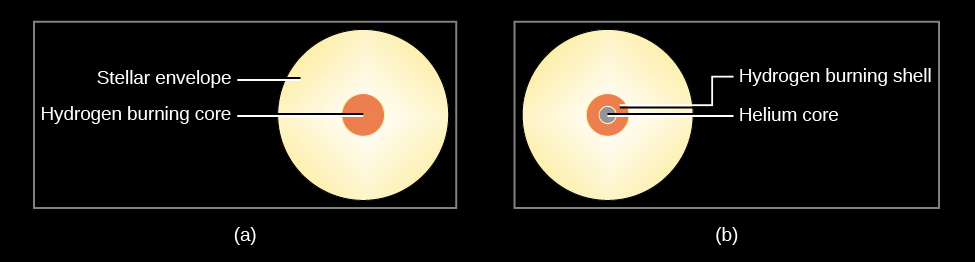

New energy produced by fusion of this hydrogen now pours outward from this shell and begins to heat up layers of the star farther out, causing them to expand. Meanwhile, the helium core continues to contract, producing more heat right around it. This leads to more fusion in the shell of fresh hydrogen outside the core (Figure 22.1.1). The additional fusion produces still more energy, which also flows out into the upper layer of the star.

Most stars actually generate more energy each second when they are fusing hydrogen in the shell surrounding the helium core than they did when hydrogen fusion was confined to the central part of the star; thus, they increase in luminosity. With all the new energy pouring outward, the outer layers of the star begin to expand, and the star eventually grows and grows until it reaches enormous proportions (22.1.2).

When you take the lid off a pot of boiling water, the steam can expand and it cools down. In the same way, the expansion of a star’s outer layers causes the temperature at the surface to decrease. As it cools, the star’s overall color becomes redder. (We saw in Radiation and Spectra that a red color corresponds to cooler temperature.)

So the star becomes simultaneously more luminous and cooler. On the H–R diagram, the star therefore leaves the main-sequence band and moves upward (brighter) and to the right (cooler surface temperature). Over time, massive stars become red supergiants, and lower-mass stars like the Sun become red giants. (We first discussed such giant stars in The Stars: A Celestial Census; here we see how such “swollen” stars originate.) You might also say that these stars have “split personalities”: their cores are contracting while their outer layers are expanding. (Note that red giant stars do not actually look deep red; their colors are more like orange or orange-red.)

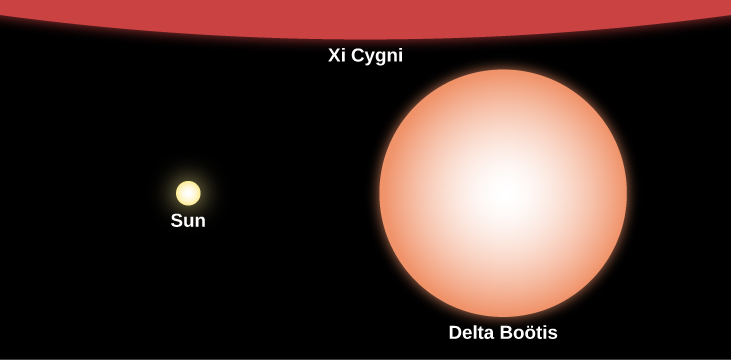

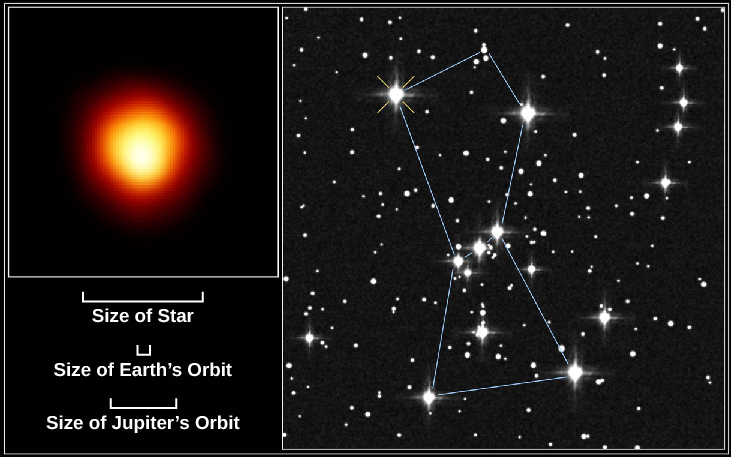

Just how different are these red giants and supergiants from a main-sequence star? Table 22.1.2 compares the Sun with the red supergiant Betelgeuse, which is visible above Orion’s belt as the bright red star that marks the hunter’s armpit. Relative to the Sun, this supergiant has a much larger radius, a much lower average density, a cooler surface, and a much hotter core.

| Property | Sun | Betelgeuse |

|---|---|---|

| Mass (2 × 1033 g) | 1 | 16 |

| Radius (km) | 700,000 | 500,000,000 |

| Surface temperature (K) | 5,800 | 3,600 |

| Core temperature (K) | 15,000,000 | 160,000,000 |

| Luminosity (4 × 1026 W) | 1 | 46,000 |

| Average density (g/cm3) | 1.4 | 1.3 × 10–7 |

| Age (millions of years) | 4,500 | 10 |

Red giants can become so large that if we were to replace the Sun with one of them, its outer atmosphere would extend to the orbit of Mars or even beyond (Figure 22.1.3). This is the next stage in the life of a star as it moves (to continue our analogy to human lives) from its long period of “youth” and “adulthood” to “old age.” (After all, many human beings today also see their outer layers expand a bit as they get older.) By considering the relative ages of the Sun and Betelgeuse, we can also see that the idea that “bigger stars die faster” is indeed true here. Betelgeuse is a mere 10 million years old, which is relatively young compared with our Sun’s 4.5 billion years, but it is already nearing its death throes as a red supergiant.

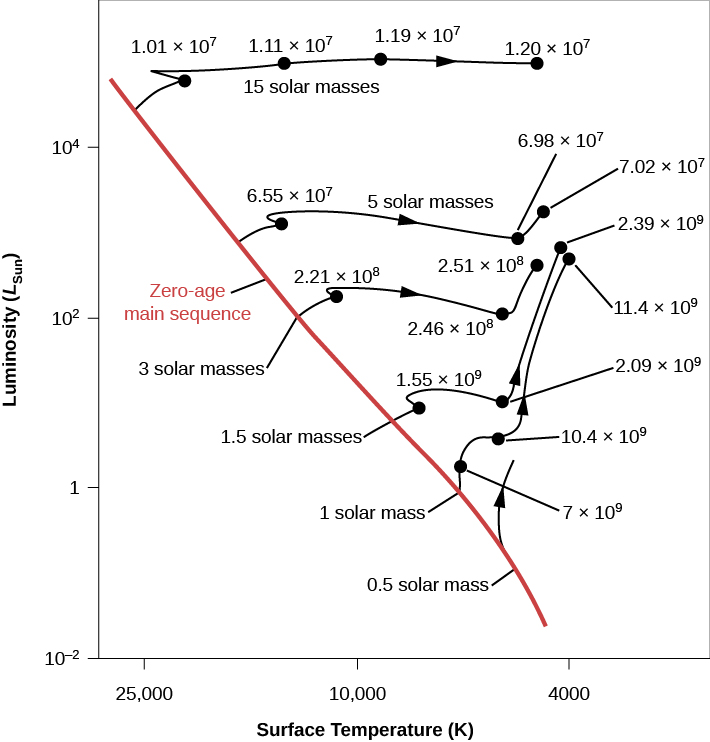

Models for Evolution to the Giant Stage

As we discussed earlier, astronomers can construct computer models of stars with different masses and compositions to see how stars change throughout their lives. 22.1.4, which is based on theoretical calculations by University of Illinois astronomer Icko Iben, shows an H–R diagram with several tracks of evolution from the main sequence to the giant stage. Tracks are shown for stars with different masses (from 0.5 to 15 times the mass of our Sun) and with chemical compositions similar to that of the Sun. The red line is the initial or zero-age main sequence. The numbers along the tracks indicate the time, in years, required for each star to reach those points in their evolution after leaving the main sequence. Once again, you can see that the more massive a star is, the more quickly it goes through each stage in its life.

Note that the most massive star in this diagram has a mass similar to that of Betelgeuse, and so its evolutionary track shows approximately the history of Betelgeuse. The track for a 1-solar-mass star shows that the Sun is still in the main-sequence phase of evolution, since it is only about 4.5 billion years old. It will be billions of years before the Sun begins its own “climb” away from the main sequence—the expansion of its outer layers that will make it a red giant.

Key Concepts and Summary

When stars first begin to fuse hydrogen to helium, they lie on the zero-age main sequence. The amount of time a star spends in the main-sequence stage depends on its mass. More massive stars complete each stage of evolution more quickly than lower-mass stars. The fusion of hydrogen to form helium changes the interior composition of a star, which in turn results in changes in its temperature, luminosity, and radius. Eventually, as stars age, they evolve away from the main sequence to become red giants or supergiants. The core of a red giant is contracting, but the outer layers are expanding as a result of hydrogen fusion in a shell outside the core. The star gets larger, redder, and more luminous as it expands and cools.

Glossary

- zero-age main sequence

- a line denoting the main sequence on the H–R diagram for a system of stars that have completed their contraction from interstellar matter and are now deriving all their energy from nuclear reactions, but whose chemical composition has not yet been altered substantially by nuclear reactions