24.2: Physical Pendulum

- Page ID

- 25583

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

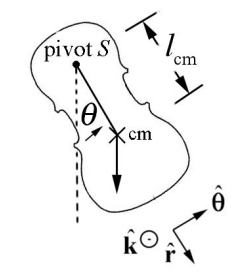

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A physical pendulum consists of a rigid body that undergoes fixed axis rotation about a fixed point \(S\) (Figure 24.2).

The gravitational force acts at the center of mass of the physical pendulum. Denote the distance of the center of mass to the pivot point \(S\) by \(l_{\mathrm{cm}}\). The torque analysis is nearly identical to the simple pendulum. The torque about the pivot point \(S\) is given by

\[\vec{\tau}_{S}=\overrightarrow{\mathbf{r}}_{S, \mathrm{cm}} \times m \overrightarrow{\mathrm{g}}=l_{\mathrm{cm}} \hat{\mathbf{r}} \times m g(\cos \theta \hat{\mathbf{r}}-\sin \theta \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}})=-l_{\mathrm{cm}} m g \sin \theta \hat{\mathbf{k}} \nonumber \]

Following the same steps that led from Equation (24.1.1) to Equation (24.1.4), the rotational equation for the physical pendulum is

\[-m g l_{\mathrm{cm}} \sin \theta=I_{S} \frac{d^{2} \theta}{d t^{2}} \nonumber \]

where \(I_{s}\) the moment of inertia about the pivot point \(S\). As with the simple pendulum, for small angles \(\sin \theta \approx \theta\), Equation (24.2.2) reduces to the simple harmonic oscillator equation

\[\frac{d^{2} \theta}{d t^{2}} \simeq-\frac{m g l_{\mathrm{cm}}}{I_{S}} \theta \nonumber \]

The equation for the angle \(\theta(t)\) is given by

\[\theta(t)=A \cos \left(\omega_{0} t\right)+B \sin \left(\omega_{0} t\right) \nonumber \]

where the angular frequency is given by

\[\omega_{0} \simeq \sqrt{\frac{m g l_{\mathrm{cm}}}{I_{S}}} \quad(\text { physical pendulum }) \nonumber \]

and the period is

\[T=\frac{2 \pi}{\omega_{0}} \simeq 2 \pi \sqrt{\frac{I_{S}}{m g l_{\mathrm{cm}}}} \quad(\text { physical pendulum }) \nonumber \]

Substitute the parallel axis theorem, \(I_{S}=m l_{\mathrm{cm}}^{2}+I_{\mathrm{cm}}\) into Equation (24.2.6) with the result that

\[T \simeq 2 \pi \sqrt{\frac{l_{\mathrm{cm}}}{g}+\frac{I_{\mathrm{cm}}}{m g l_{\mathrm{cm}}}} \quad(\text { physical pendulum }) \nonumber \]

Thus, if the object is “small” in the sense that \(I_{\mathrm{cm}}<<m l_{\mathrm{c}}^{2}\), the expressions for the physical pendulum reduce to those for the simple pendulum. The z -component of the angular velocity is given by

\[\omega_{z}(t)=\frac{d \theta}{d t}(t)=-\omega_{0} A \sin \left(\omega_{0} t\right)+\omega_{0} B \cos \left(\omega_{0} t\right) \nonumber \]

The coefficients A and B can be determined form the initial conditions by setting t = 0 in Equations (24.2.4) and (24.2.8) resulting in the conditions that

\[\begin{array}{l}

A=\theta(t=0) \equiv \theta_{0} \\

B=\frac{\omega_{z}(t=0)}{\omega_{0}} \equiv \frac{\omega_{z, 0}}{\omega_{0}}

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Therefore the equations for the angle \(\theta(t) \text { and } \omega_{z}(t)=\frac{d \theta}{d t}(t)\) are given by

\[\begin{array}{c}

\theta(t)=\theta_{0} \cos \left(\omega_{0} t\right)+\frac{\omega_{z, 0}}{\omega_{0}} \sin \left(\omega_{0} t\right) \\

\omega_{z}(t)=\frac{d \theta}{d t}(t)=-\omega_{0} \theta_{0} \sin \left(\omega_{0} t\right)+\omega_{z, 0} \cos \left(\omega_{0} t\right)

\end{array} \nonumber \]