4.2: Angular Velocity and Eulerian Angles

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

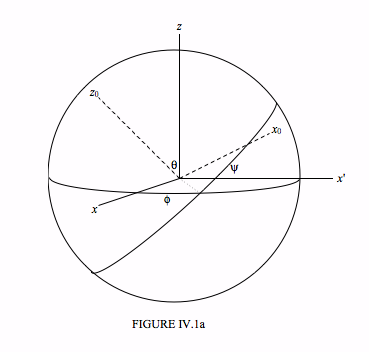

Let Oxyz be a set of space-fixed axis, and let Ox0y0z0 be the body-fixed principal axes of a rigid body.

The orientation of the body-fixed principal axes Ox0y0z0 with respect to the space-fixed axes Oxyz can be described by the three Euler angles: θ, ϕ, and ψ. These are illustrated in Figure IV.1a. Those who are not familiar with Euler angles or who would like a reminder can refer to their detailed description in Chapter 3 of my notes on Celestial Mechanics.

We are going to examine the motion of a body that is rotating about a non-principal axis. If the body is freely rotating in space with no external torques acting upon it, its angular momentum L will be constant in magnitude and direction. The angular velocity vector ω, however, will not be constant, but will wander with respect to both the space-fixed and body-fixed axes, and we shall be examining this motion. I am going to call the instantaneous components of ω relative to the body-fixed axes ω1,ω2,ω3, and its magnitude ω. As the body tumbles over and over, its Euler angles will be changing continuously. We are going to establish a geometrical relation between the instantaneous rates of change of the Euler angles and the instantaneous components of ω. That is, we are going to find how ω1,ω2 and ω3 are related to ˙θ,˙ϕ and ˙ψ.

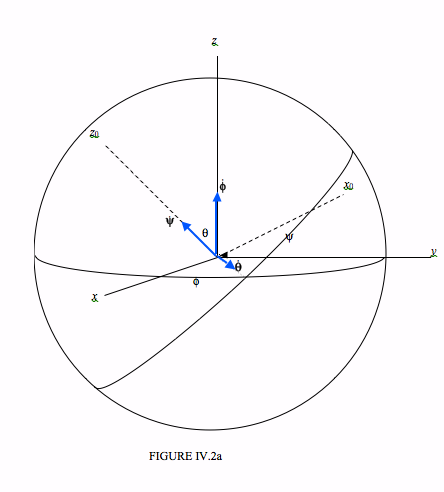

I have indicated, in Figure VI.2a, the angular velocities ˙θ,˙ϕ and ˙ψ as vectors in what I hope will be agreed are the appropriate directions.

It should be clear that ω1 is equal to the x0-component of ˙ϕ plus the x0-component of ˙θ and that ω2 is equal to the y0-component of ˙ϕ plus the y0-component of ˙θ and that ω3 is equal to the z0-component of ˙ϕ plus ˙ψ

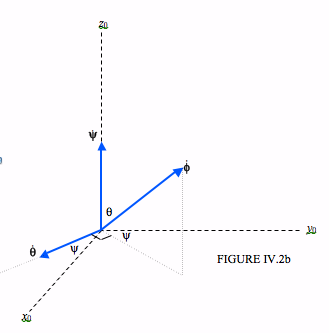

Let us look at Figure IV.2b

We see that the x0 and y0 components of ˙θ are ˙θcosψ and −˙θsinψ respectively. The x0, y0 and z0 components of ˙ϕ are, respectively:

- ˙ϕsinθsinψ,

- ˙ϕsinθsinψ, and

- ˙ϕcosθ.

Hence we arrive at

ω2=˙ϕsinθcosψ−˙θsinψ.