26.2: Precession of a Symmetrical Top

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

A more interesting case is the free rotation (zero external torque) of a symmetrical top, meaning I1=I2≠I3.

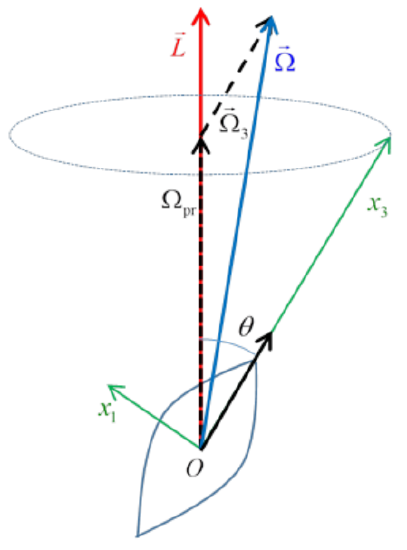

We can take any pair of orthogonal axes, perpendicular to the body’s symmetry axis, as the x1,x2 axes. We’ll choose x2 following Landau, as perpendicular to the plane containing →L and the momentary position of the x3 axis, so in the diagram here x2 is perpendicularly out from the paper/screen, towards the viewer.

This means the angular momentum component L2=0 and therefore Ω2=0. Hence →Ω is in the same plane as →L,x3, and so the velocity →v=→Ω×→r of every point on the axis of the top is perpendicular to this plane (into the paper/screen). The axis of the top Ox3 must be rotating uniformly about the direction of →L.

The spin rate of the top around its own axis is

Ω3=L3/I3=(L/I3)cosθ

The angular velocity vector →Ω can be written as a sum of two components, one along the body’s axis Ox3 and one parallel to the angular momentum →L (these components are shown dashed in the figure)

→Ω=→Ωprecession +→Ω3

The component along the body’s axis Ox3 does not contribute to the precession, which all comes from the component along the (fixed in space) angular momentum vector.

The speed of precession follows from

Ωprecession sinθ=Ω1

and

Ω1=L1/I1=(L/I1)sinθ

so

Ωprecession =L/I1

Note also the ratio of precession rate to spin around axis is

Ωprecession /Ω3=(I3/I1)secθ

This means the precession rate and the spin are very comparable, except when θ is near π/2, when the precession becomes much faster. Remember this is the body’s precession with no external torque, and is clearly completely different—much faster precession—than the familiar case of a fast spinning top under gravity.