1.2: Physical Quantities and Units

- Page ID

- 1478

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Perform unit conversions both in the SI and English units.

- Explain the most common prefixes in the SI units and be able to write them in scientific notation.

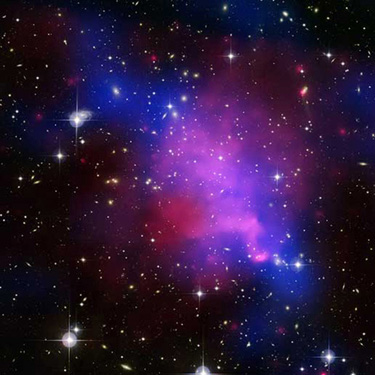

The range of objects and phenomena studied in physics is immense. From the incredibly short lifetime of a nucleus to the age of the Earth, from the tiny sizes of sub-nuclear particles to the vast distance to the edges of the known universe, from the force exerted by a jumping flea to the force between Earth and the Sun, there are enough factors of \(10\) to challenge the imagination of even the most experienced scientist. Giving numerical values for physical quantities and equations for physical principles allows us to understand nature much more deeply than does qualitative description alone. To comprehend these vast ranges, we must also have accepted units in which to express them. And we shall find that (even in the potentially mundane discussion of meters, kilograms, and seconds) a profound simplicity of nature appears—all physical quantities can be expressed as combinations of only four fundamental physical quantities: length, mass, time, and electric current.

We define a physical quantity either by specifying how it is measured or by stating how it is calculated from other measurements. For example, we define distance and time by specifying methods for measuring them, whereas we define average speed by stating that it is calculated as distance traveled divided by time of travel.

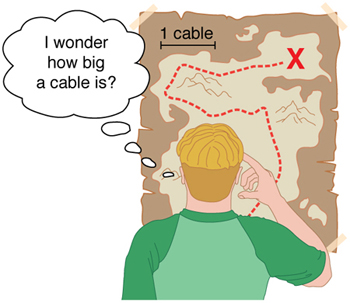

Measurements of physical quantities are expressed in terms of units, which are standardized values. For example, the length of a race, which is a physical quantity, can be expressed in units of meters (for sprinters) or kilometers (for distance runners). Without standardized units, it would be extremely difficult for scientists to express and compare measured values in a meaningful way (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

There are two major systems of units used in the world: SI units (also known as the metric system) and English units (also known as the customary or imperial system). English units were historically used in nations once ruled by the British Empire and are still widely used in the United States. Virtually every other country in the world now uses SI units as the standard; the metric system is also the standard system agreed upon by scientists and mathematicians. The acronym “SI” is derived from the French Système International.

SI Units: Fundamental and Derived Units

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) gives the fundamental SI units that are used throughout this textbook. This text uses non-SI units in a few applications where they are in very common use, such as the measurement of blood pressure in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Whenever non-SI units are discussed, they will be tied to SI units through conversions.

| Length | Mass | Time | Electric Current |

|---|---|---|---|

| meter (m) | kilogram (kg) | second (s) | ampere (A) |

It is an intriguing fact that some physical quantities are more fundamental than others and that the most fundamental physical quantities can be defined only in terms of the procedure used to measure them. The units in which they are measured are thus called fundamental units. In this textbook, the fundamental physical quantities are taken to be length, mass, time, and electric current. (Note that electric current will not be introduced until much later in this text.) All other physical quantities, such as force and electric charge, can be expressed as algebraic combinations of length, mass, time, and current (for example, speed is length divided by time); these units are called derived units.

Units of Time, Length, and Mass: The Second, Meter, and Kilogram

The Second

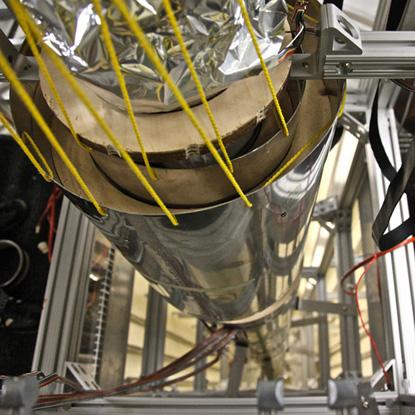

The SI unit for time, the second (abbreviated s), has a long history. For many years it was defined as 1/86,400 of a mean solar day. More recently, a new standard was adopted to gain greater accuracy and to define the second in terms of a non-varying, or constant, physical phenomenon (because the solar day is getting longer due to very gradual slowing of the Earth’s rotation). Cesium atoms can be made to vibrate in a very steady way, and these vibrations can be readily observed and counted. In 1967, the second was redefined as the time required for 9,192,631,770 of these vibrations (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Accuracy in the fundamental units is essential, because all measurements are ultimately expressed in terms of fundamental units and can be no more accurate than are the fundamental units themselves.

The Meter

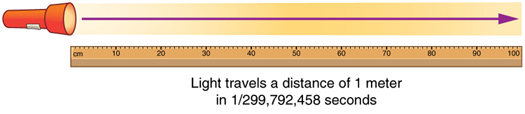

The SI unit for length is the meter (abbreviated m); its definition has also changed over time to become more accurate and precise. The meter was first defined in 1791 as 1/10,000,000 of the distance from the equator to the North Pole. This measurement was improved in 1889 by redefining the meter to be the distance between two engraved lines on a platinum-iridium bar now kept near Paris. By 1960, it had become possible to define the meter even more accurately in terms of the wavelength of light, so it was again redefined as 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of orange light emitted by krypton atoms. In 1983, the meter was given its present definition (partly for greater accuracy) as the distance light travels in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 of a second (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). This change defines the speed of light to be exactly 299,792,458 meters per second. The length of the meter will change if the speed of light is someday measured with greater accuracy.

The Kilogram

The SI unit for mass is the kilogram (abbreviated kg); it is defined to be the mass of a platinum-iridium cylinder kept with the old meter standard at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures near Paris. Exact replicas of the standard kilogram are also kept at the United States’ National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, located in Gaithersburg, Maryland outside of Washington D.C., and at other locations around the world. The determination of all other masses can be ultimately traced to a comparison with the standard mass.

Electric current and its accompanying unit, the ampere, will be introduced in Introduction to Electric Current, Resistance, and Ohm's Law when electricity and magnetism are covered. The initial modules in this textbook are concerned with mechanics, fluids, heat, and waves. In these subjects all pertinent physical quantities can be expressed in terms of the fundamental units of length, mass, and time.

Metric Prefixes

SI units are part of the metric system. The metric system is convenient for scientific and engineering calculations because the units are categorized by factors of 10. Table 2 gives metric prefixes and symbols used to denote various factors of 10.

Metric systems have the advantage that conversions of units involve only powers of 10. There are 100 centimeters in a meter, 1000 meters in a kilometer, and so on. In nonmetric systems, such as the system of U.S. customary units, the relationships are not as simple—there are 12 inches in a foot, 5280 feet in a mile, and so on. Another advantage of the metric system is that the same unit can be used over extremely large ranges of values simply by using an appropriate metric prefix. For example, distances in meters are suitable in construction, while distances in kilometers are appropriate for air travel, and the tiny measure of nanometers are convenient in optical design. With the metric system there is no need to invent new units for particular applications.

The term order of magnitude refers to the scale of a value expressed in the metric system. Each power of 1 0 in the metric system represents a different order of magnitude. For example, 101, 102, 103 , and so forth are all different orders of magnitude. All quantities that can be expressed as a product of a specific power of 10 are said to be of the same order of magnitude. For example, the number 800 can be written as 8×102 , and the number 450 can be written as 4.5×102. Thus, the numbers 800 and 450 are of the same order of magnitude: 102. Order of magnitude can be thought of as a ballpark estimate for the scale of a value. The diameter of an atom is on the order of 10-9 m, while the diameter of the Sun is on the order of 109 m.

THE QUEST FOR MICROSCOPIC STANDARDS FOR BASIC UNITS

The fundamental units described in this chapter are those that produce the greatest accuracy and precision in measurement. There is a sense among physicists that, because there is an underlying microscopic substructure to matter, it would be most satisfying to base our standards of measurement on microscopic objects and fundamental physical phenomena such as the speed of light. A microscopic standard has been accomplished for the standard of time, which is based on the oscillations of the cesium atom.

The standard for length was once based on the wavelength of light (a small-scale length) emitted by a certain type of atom, but it has been supplanted by the more precise measurement of the speed of light. If it becomes possible to measure the mass of atoms or a particular arrangement of atoms such as a silicon sphere to greater precision than the kilogram standard, it may become possible to base mass measurements on the small scale. There are also possibilities that electrical phenomena on the small scale may someday allow us to base a unit of charge on the charge of electrons and protons, but at present current and charge are related to large-scale currents and forces between wires.

| Prefix | Symbol | Value | Examples (some are Approximate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| exa | E | \(10^18\) | exameter Em \(10^{18}m\) | distance light travels in a century |

| peta | P | \(10^15\) | petasecond Ps \(10^{15} s\) | 30 million years |

| tera | T | \(10^12\) | terawatt TW \(10^{12} W\) | powerful laser output |

| giga | G | \(10^9\) | gigahertz GHz \(10^9 Hz\) | a microwave frequency |

| mega | M | \(10^6\) | megacurie MCi \(10^{6 }Ci\) | high radioactivity |

| kilo | k | \(10^3\) | kilometer km \(10^3 m\) | about 6/10 mile |

| hecto | h | \(10^2\) | hectoliter hL \(10^2 L\) | 26 gallons |

| deka | da | \(10^1\) | dekagram dag \(10^g\) | teaspoon of butter |

| — | — | \(10^0 (=1)\) | ||

| deci | d | \(10^{−1}\) | deciliter dL \(10^{−1} L\) | less than half a soda |

| centi | c | \(10^{−2}\) | centimeter cm \(10^{−2} m\) | fingertip thickness |

| milli | m | \(10^{−3}\) | millimeter mm \(10^{−3} m\) | flea at its shoulders |

| micro | µ | \(10^{−6}\) | micrometer µm \(10^{−6} m\) | detail in microscope |

| nano | n | \(10^{−9}\) | nanogram ng \(10^{−9} g\) | small speck of dust |

| pico | p | \(10^{−12}\) | picofarad pF \(10^{−12} F\) | small capacitor in radio |

| femto | f | \(10^{−15}\) | femtometer fm \(10^{−15} m\) | size of a proton |

| atto | a | \(10^{−18}\) | attosecond as \(10^{−18} s\) | time light crosses an atom |

Known Ranges of Length, Mass, and Time

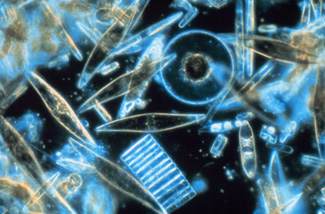

The vastness of the universe and the breadth over which physics applies are illustrated by the wide range of examples of known lengths, masses, and times in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\). Examination of this table will give you some feeling for the range of possible topics and numerical values (Figures \(\PageIndex{5}\) and \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

Unit Conversion and Dimensional Analysis

It is often necessary to convert from one type of unit to another. For example, if you are reading a European cookbook, some quantities may be expressed in units of liters and you need to convert them to cups. Or, perhaps you are reading walking directions from one location to another and you are interested in how many miles you will be walking. In this case, you will need to convert units of feet to miles. Let us consider a simple example of how to convert units.

Let us say that we want to convert 80 meters (\(m\)) to kilometers (\(km\)).

- The first thing to do is to list the units that you have and the units that you want to convert to. In this case, we have units in meters and we want to convert to kilometers.

- Next, we need to determine a conversion factor relating meters to kilometers. A conversion factor is a ratio expressing how many of one unit are equal to another unit. For example, there are 12 inches in 1 foot, 100 centimeters in 1 meter, 60 seconds in 1 minute, and so on. In this case, we know that there are 1,000 meters in 1 kilometer.

- Now we can set up our unit conversion. We will write the units that we have and then multiply them by the conversion factor so that the units cancel out, as shown: \[80\,\cancel{m} \times \dfrac{1\,km}{1000\,\cancel{m}} =0.08\, km\] Note that the unwanted \(m\) unit cancels, leaving only the desired km unit. You can use this method to convert between any types of unit.

Click Appendix C for a more complete list of conversion factors.

| lengths in meters | Masses in kilograms (more precise values in parentheses) | Times in seconds (more precise values in parentheses) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10−18 | Present experimental limit to smallest observable detail |

10−30

|

Mass of an electron (9.11×10−31 kg) |

10−23

|

Time for light to cross a proton |

|

10−15

|

Diameter of a proton |

10−27

|

Mass of a hydrogen atom (1.67×10−27 kg) |

10−22

|

Mean life of an extremely unstable nucleus |

|

10−14

|

Diameter of a uranium nucleus |

10−15

|

Mass of a bacterium |

10−15

|

Time for one oscillation of visible light |

|

10−10

|

Diameter of a hydrogen atom |

10−5

|

Mass of a mosquito |

10−13 |

Time for one vibration of an atom in a solid |

|

10−8

|

Thickness of membranes in cells of living organisms |

10−2

|

Mass of a hummingbird |

10−8

|

Time for one oscillation of an FM radio wave |

|

10−6

|

Wavelength of visible light |

1

|

Mass of a liter of water (about a quart) |

10−3

|

Duration of a nerve impulse |

|

10−3

|

Size of a grain of sand |

102

|

Mass of a person |

1

|

Time for one heartbeat |

|

1

|

Height of a 4-year-old child |

103

|

Mass of a car |

105

|

One day (8.64×104s) |

|

102

|

Length of a football field |

108

|

Mass of a large ship |

107

|

One year (y) (3.16×107s) |

|

104

|

Greatest ocean depth |

1012

|

Mass of a large iceberg |

109

|

About half the life expectancy of a human |

|

107

|

Diameter of the Earth |

1015

|

Mass of the nucleus of a comet |

1011

|

Recorded history |

|

1011

|

Distance from the Earth to the Sun |

1023

|

Mass of the Moon (7.35×1022 kg) |

1017

|

Age of the Earth |

|

1016

|

Distance traveled by light in 1 year (a light year) |

1025

|

Mass of the Earth (5.97×1024 kg) |

1018

|

Age of the universe |

|

1021 |

Diameter of the Milky Way galaxy |

1030

|

Mass of the Sun (1.99×1030 kg) | ||

|

1022

|

Distance from the Earth to the nearest large galaxy (Andromeda) |

1042

|

Mass of the Milky Way galaxy (current upper limit) | ||

|

1026

|

Distance from the Earth to the edges of the known universe |

1053

|

Mass of the known universe (current upper limit) | ||

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Unit Conversions: A Short Drive Home

Suppose that you drive the 10.0 km from your university to home in 20.0 min. Calculate your average speed (a) in kilometers per hour (km/h) and (b) in meters per second (m/s). (Note: Average speed is distance traveled divided by time of travel.)

Strategy

First we calculate the average speed using the given units. Then we can get the average speed into the desired units by picking the correct conversion factor and multiplying by it. The correct conversion factor is the one that cancels the unwanted unit and leaves the desired unit in its place.

Solution for (a)

(1) Calculate average speed. Average speed is distance traveled divided by time of travel. (Take this definition as a given for now—average speed and other motion concepts will be covered in a later module.) In equation form,

\[\text{average speed} =\dfrac{distance}{time}. \nonumber\]

(2) Substitute the given values for distance and time.

\[ \begin{align*} \text{average speed} &=\dfrac{10.0\, km}{20.0\, min} \\[5pt] &=0.500 \dfrac{km}{ min}.\end{align*} \]

(3) Convert km/min to km/h: multiply by the conversion factor that will cancel minutes and leave hours. That conversion factor is 60 min/hr. Thus,

\[\begin{align*} \text{average speed} &=0.500 \dfrac{km}{ min}×\dfrac{60\, min}{1 \,h} \\[5pt] &=30.0 \dfrac{km}{ h} \end{align*} \]

Discussion for (a)

To check your answer, consider the following:

(1) Be sure that you have properly cancelled the units in the unit conversion. If you have written the unit conversion factor upside down, the units will not cancel properly in the equation. If you accidentally get the ratio upside down, then the units will not cancel; rather, they will give you the wrong units as follows:

\[\dfrac{km}{min}×\dfrac{1\, hr}{60\, min}=\dfrac{1}{60} \dfrac{km⋅hr}{ min^2}, \nonumber\]

which are obviously not the desired units of km/h.

(2) Check that the units of the final answer are the desired units. The problem asked us to solve for average speed in units of km/h and we have indeed obtained these units.

(3) Check the significant figures. Because each of the values given in the problem has three significant figures, the answer should also have three significant figures. The answer 30.0 km/hr does indeed have three significant figures, so this is appropriate. Note that the significant figures in the conversion factor are not relevant because an hour is defined to be 60 minutes, so the precision of the conversion factor is perfect.

(4) Next, check whether the answer is reasonable. Let us consider some information from the problem—if you travel 10 km in a third of an hour (20 min), you would travel three times that far in an hour. The answer does seem reasonable.

Solution for (b)

There are several ways to convert the average speed into meters per second.

(1) Start with the answer to (a) and convert km/h to m/s. Two conversion factors are needed—one to convert hours to seconds, and another to convert kilometers to meters.

(2) Multiplying by these yields

\[\begin{align*} \text{Average speed} &=30.0\dfrac{\bcancel{km}}{\cancel{h}}×\dfrac{1\,\cancel{h}}{3,600 \,s}×\dfrac{1,000\,m}{1\, \bcancel{km}} \\[5pt] &=8.33 \,m/s \end{align*}\]

Discussion for (b)

If we had started with 0.500 km/min, we would have needed different conversion factors, but the answer would have been the same: 8.33 m/s.

You may have noted that the answers in the worked example just covered were given to three digits. Why? When do you need to be concerned about the number of digits in something you calculate? Why not write down all the digits your calculator produces? The module Accuracy, Precision, and Significant Figures will help you answer these questions.

NONSTANDARD UNITS

While there are numerous types of units that we are all familiar with, there are others that are much more obscure. For example, a firkin is a unit of volume that was once used to measure beer. One firkin equals about 34 liters. To learn more about nonstandard units, use a dictionary or encyclopedia to research different “weights and measures.” Take note of any unusual units, such as a barleycorn, that are not listed in the text. Think about how the unit is defined and state its relationship to SI units.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Some hummingbirds beat their wings more than 50 times per second. A scientist is measuring the time it takes for a hummingbird to beat its wings once. Which fundamental unit should the scientist use to describe the measurement? Which factor of 10 is the scientist likely to use to describe the motion precisely? Identify the metric prefix that corresponds to this factor of 10.

- Answer

-

The scientist will measure the time between each movement using the fundamental unit of seconds. Because the wings beat so fast, the scientist will probably need to measure in milliseconds, or 10−3 seconds. (50 beats per second corresponds to 20 milliseconds per beat.)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

One cubic centimeter is equal to one milliliter. What does this tell you about the different units in the SI metric system?

- Answer

-

The fundamental unit of length (meter) is probably used to create the derived unit of volume (liter). The measure of a milliliter is dependent on the measure of a centimeter.

Summary

- Physical quantities are a characteristic or property of an object that can be measured or calculated from other measurements.

- Units are standards for expressing and comparing the measurement of physical quantities. All units can be expressed as combinations of four fundamental units.

- The four fundamental units we will use in this text are the meter (for length), the kilogram (for mass), the second (for time), and the ampere (for electric current). These units are part of the metric system, which uses powers of 10 to relate quantities over the vast ranges encountered in nature.

- The four fundamental units are abbreviated as follows: meter, m; kilogram, kg; second, s; and ampere, A. The metric system also uses a standard set of prefixes to denote each order of magnitude greater than or lesser than the fundamental unit itself.

- Unit conversions involve changing a value expressed in one type of unit to another type of unit. This is done by using conversion factors, which are ratios relating equal quantities of different units.

Glossary

- physical quantity

- a characteristic or property of an object that can be measured or calculated from other measurements

- units

- a standard used for expressing and comparing measurements

- SI units

- the international system of units that scientists in most countries have agreed to use; includes units such as meters, liters, and grams

- English units

- system of measurement used in the United States; includes units of measurement such as feet, gallons, and pounds

- fundamental units

- units that can only be expressed relative to the procedure used to measure them

- derived units

- units that can be calculated using algebraic combinations of the fundamental units

- second

- the SI unit for time, abbreviated (s)

- meter

- the SI unit for length, abbreviated (m)

- kilogram

- the SI unit for mass, abbreviated (kg)

- metric system

- a system in which values can be calculated in factors of 10

- order of magnitude

- refers to the size of a quantity as it relates to a power of 10

- conversion factor

- a ratio expressing how many of one unit are equal to another unit