6.2: Centripetal Acceleration

- Page ID

- 1510

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Establish the expression for centripetal acceleration.

- Explain the centrifuge.

We know from kinematics that acceleration is a change in velocity, either in its magnitude or in its direction, or both. In uniform circular motion, the direction of the velocity changes constantly, so there is always an associated acceleration, even though the magnitude of the velocity might be constant. You experience this acceleration yourself when you turn a corner in your car. (If you hold the wheel steady during a turn and move at constant speed, you are in uniform circular motion.) What you notice is a sideways acceleration because you and the car are changing direction. The sharper the curve and the greater your speed, the more noticeable this acceleration will become. In this section we examine the direction and magnitude of that acceleration.

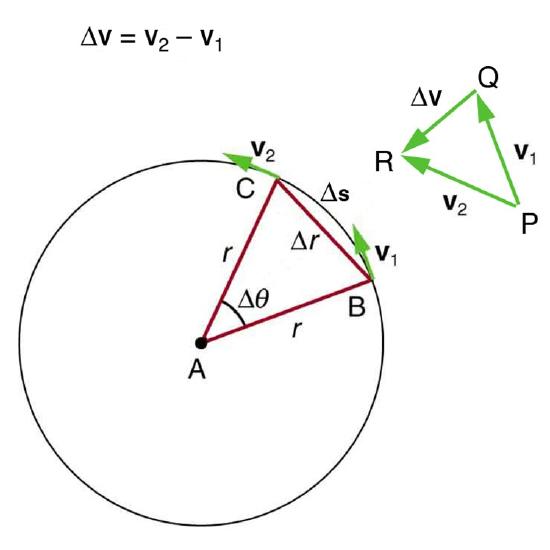

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows an object moving in a circular path at constant speed. The direction of the instantaneous velocity is shown at two points along the path. Acceleration is in the direction of the change in velocity, which points directly toward the center of rotation (the center of the circular path). This pointing is shown with the vector diagram in the figure. We call the acceleration of an object moving in uniform circular motion (resulting from a net external force) the centripetal acceleration \(a_c\); centripetal means “toward the center” or “center seeking.”

The direction of centripetal acceleration is toward the center of curvature, but what is its magnitude? Note that the triangle formed by the velocity vectors and the one formed by the radii \(r\) and \(\Delta s\) are similar. Both the triangles ABC and PQR are isosceles triangles (two equal sides). The two equal sides of the velocity vector triangle are the speeds \( v_1 =v_2 = v \) Using the properties of two similar triangles, we obtain

\[ \dfrac{\Delta v}{v} = \dfrac{\Delta s}{r}. \]

Acceleration is \(\Delta v/\Delta t \) and so we first solve this expression for \(\delta v \):

\[\delta v = \dfrac{v}{r} \Delta s. \]

Then we divide this by \(\Delta t \), yielding

\[\dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} = \dfrac{v}{r} \times \dfrac{\Delta s}{\Delta t}. \]

Finally, noting that \( \Delta v/\Delta t = a_c \) and that \(\delta s/\Delta t = v \) the linear or tangential speed, we see that the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration is

\[ a_c = \dfrac{v^2}{r}, \]

which is the acceleration of an object in a circle of radius \(r\) at a speed \(v\).

So, centripetal acceleration is greater at high speeds and in sharp curves (smaller radius), as you have noticed when driving a car. But it is a bit surprising that \(a_c\) is proportional to speed squared, implying, for example, that it is four times as hard to take a curve at 100 km/h than at 50 km/h. A sharp corner has a small radius, so that \(a_c\) is greater for tighter turns, as you have probably noticed.It is also useful to express \(a_c\) in terms of angular velocity. Substituting \( v = r\omega \) into the above expression, we find \( a_c = (r \omega^2)/r = r \omega^2 \). We can express the magnitude of centripetal acceleration using either of two equations:

\[ a_c = \dfrac{v^2}{r}; \, a_c = r \omega^2 \]

Recall that the direction of \(a_c\) is toward the center. You may use whichever expression is more convenient, as illustrated in examples below.

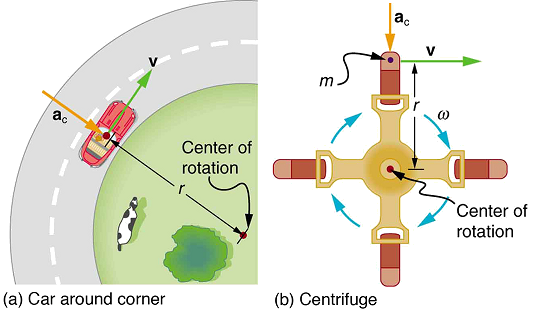

A centrifuge (Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\)) is a rotating device used to separate specimens of different densities. High centripetal acceleration significantly decreases the time it takes for separation to occur, and makes separation possible with small samples. Centrifuges are used in a variety of applications in science and medicine, including the separation of single cell suspensions such as bacteria, viruses, and blood cells from a liquid medium and the separation of macromolecules, such as DNA and protein, from a solution. Centrifuges are often rated in terms of their centripetal acceleration relative to acceleration due to gravity \((g)\) maximum centripetal acceleration of several hundred thousand \(g\) is possible in a vacuum. Human centrifuges, extremely large centrifuges, have been used to test the tolerance of astronauts to the effects of accelerations larger than that of Earth’s gravity.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Centripetal Acceleration vs. Gravity?

What is the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration of a car following a curve of radius 500 m at a speed of 25.0 m/s (about 90 km/h)? Compare the acceleration with that due to gravity for this fairly gentle curve taken at highway speed. See Figure \(\PageIndex{2a}\).

Strategy

Because \(v\) and \(r\) are given, the first expression in \( a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}: \, a_c = r \omega^2 \) is the most convenient to use.

Solution

Entering the given values of \( v = 25.0 \, m/s and r = 500 \, m \) into the first expression for \(a_c\) gives

\[a_c = \dfrac{v^2}{r} = \dfrac{(25.0 m/s)^2}{500 \, m} = 1.25 \, m/s^2. \nonumber \]

Discussion

To compare this with the acceleration due to gravity \( (g = 9.80 \, m/s^2) \), we take the ratio of \(a_c/g = (1.25 \, m/s^2)/(9.80 \, m/s^2) = 0.128. \) Thus, \(a_c = 0.128 g \) and is noticeable especially if you were not wearing a seat belt.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): How Big is the Centripetal Acceleration in an Ultracentrifuge?

Calculate the centripetal acceleration of a point 7.50 cm from the axis of an ultracentrifuge spinning at \(7.4 \times 10^7 \, rev/min.\) Determine the ratio of this acceleration to that due to gravity. See Figure Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\).

Strategy

The term rev/min stands for revolutions per minute. By converting this to radians per second, we obtain the angular velocity \(\omega\). Because \(r\) is given, we can use the second expression in the equation \(a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}; \, a_c = r\omega^2 \) to calculate the centripetal acceleration.

Solution

To convert \(7.40 \times 10^4 \, rev/min \) to radians per second, we use the facts that one revolution is \(2\pi \, rad\) and one minute is 60.0 s. Thus,

\[\omega = 7.40 \times 10^4 \dfrac{rev}{min} \times \dfrac{2 \pi \, rad}{1 \, rev} \times \dfrac{1 \, min}{60 \, sec} = 7745 \, rad/sec. \nonumber \]

Now the centripetal acceleration is given by the second expression in \( a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}; \, a_c = r\omega^2\) as

\[ a_c = r\omega^2. \nonumber\]

Converting 7.50 cm to meters and substituting known values gives

\[a_c = (0.0750 \, m)(7854 \, rad/sec)^2 = 4.50 \times 10^6 \, m/s^2. \nonumber\]

Note that the unitless radians are discarded in order to get the correct units for centripetal acceleration. Taking the ratio of \(a_c\) to \(g\) yields

\[\dfrac{a_c}{g} = \dfrac{4.63 \times 10^6}{9.80} = 4.59 \times 10^5. \nonumber\]

Discussion

This last result means that the centripetal acceleration is 472,000 times as strong as \(g\). It is no wonder that such high \(\omega\) centrifuges are called ultracentrifuges. The extremely large accelerations involved greatly decrease the time needed to cause the sedimentation of blood cells or other materials.

Of course, a net external force is needed to cause any acceleration, just as Newton proposed in his second law of motion. So a net external force is needed to cause a centripetal acceleration. In the section on Centripetal Force, we will consider the forces involved in circular motion.

PHET EXPLORATIONS: LADYBUG MOTION 2D

Learn about position, velocity and acceleration vectors. Move the ladybug by setting the position, velocity or acceleration, and see how the vectors change. Choose linear, circular or elliptical motion, and record and playback the motion to analyze the behavior.

Summary

- Centripetal acceleration \(a_c\) is the acceleration experienced while in uniform circular motion. It always points toward the center of rotation. It is perpendicular to the linear velocity \(v\) and has the magnitude \[a_c = \dfrac{v^2}{r}; \, a_c = r\omega^2. \nonumber \]

- The unit of centripetal acceleration is \(m/s^2.\)

Glossary

- centripetal acceleration

- the acceleration of an object moving in a circle, directed toward the center

- ultracentrifuge

- a centrifuge optimized for spinning a rotor at very high speeds