15.4: Carnot’s Perfect Heat Engine- The Second Law of Thermodynamics Restated

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify a Carnot cycle.

- Calculate maximum theoretical efficiency of a nuclear reactor.

- Explain how dissipative processes affect the ideal Carnot engine.

We know from the second law of thermodynamics that a heat engine cannot be 100% efficient, since there must always be some heat transfer Qc to the environment, which is often called waste heat. How efficient, then, can a heat engine be? This question was answered at a theoretical level in 1824 by a young French engineer, Sadi Carnot (1796–1832), in his study of the then-emerging heat engine technology crucial to the Industrial Revolution. He devised a theoretical cycle, now called the Carnot cycle, which is the most efficient cyclical process possible. The second law of thermodynamics can be restated in terms of the Carnot cycle, and so what Carnot actually discovered was this fundamental law. Any heat engine employing the Carnot cycle is called a Carnot engine.

What is crucial to the Carnot cycle—and, in fact, defines it—is that only reversible processes are used. Irreversible processes involve dissipative factors, such as friction and turbulence. This increases heat transfer Qc to the environment and reduces the efficiency of the engine. Obviously, then, reversible processes are superior.

Carnot Engine

Stated in terms of reversible processes, the second law of thermodynamics has a third form:

A Carnot engine operating between two given temperatures has the greatest possible efficiency of any heat engine operating between these two temperatures. Furthermore, all engines employing only reversible processes have this same maximum efficiency when operating between the same given temperatures.

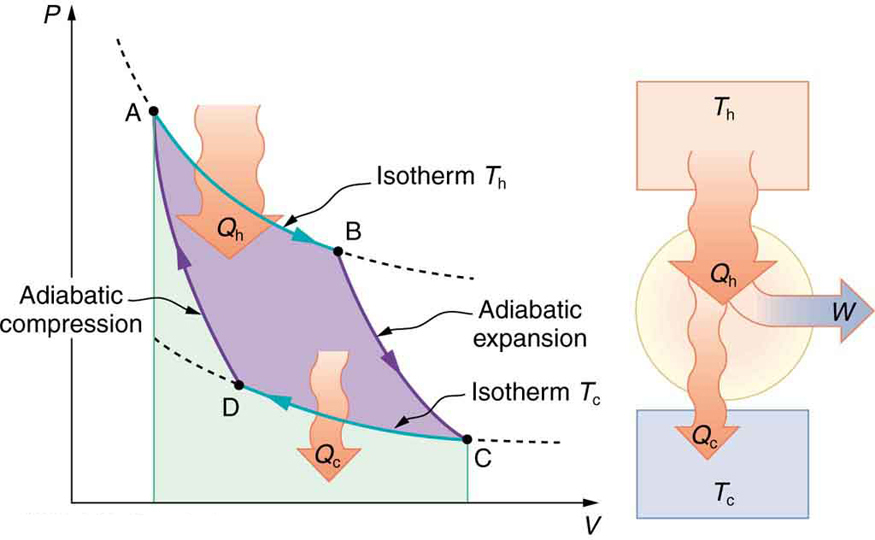

Figure 15.4.2 shows the PV diagram for a Carnot cycle. The cycle comprises two isothermal and two adiabatic processes. Recall that both isothermal and adiabatic processes are, in principle, reversible.

Carnot also determined the efficiency of a perfect heat engine—that is, a Carnot engine. It is always true that the efficiency of a cyclical heat engine is given by: Eff=Qh−QcQh=1−QcQh.

Carnot’s interesting result implies that 100% efficiency would be possible only if Tc=0 - that is, only if the cold reservoir were at absolute zero, a practical and theoretical impossibility. But the physical implication is this—the only way to have all heat transfer go into doing work is to remove all thermal energy, and this requires a cold reservoir at absolute zero.

It is also apparent that the greatest efficiencies are obtained when the ratio Tc/Th is as small as possible. Just as discussed for the Otto cycle in the previous section, this means that efficiency is greatest for the highest possible temperature of the hot reservoir and lowest possible temperature of the cold reservoir. (This setup increases the area inside the closed loop on the PV diagram; also, it seems reasonable that the greater the temperature difference, the easier it is to divert the heat transfer to work.) The actual reservoir temperatures of a heat engine are usually related to the type of heat source and the temperature of the environment into which heat transfer occurs. Consider the following example.

Example 15.4.1: Maximum Theoretical Efficiency for a Nuclear Reactor

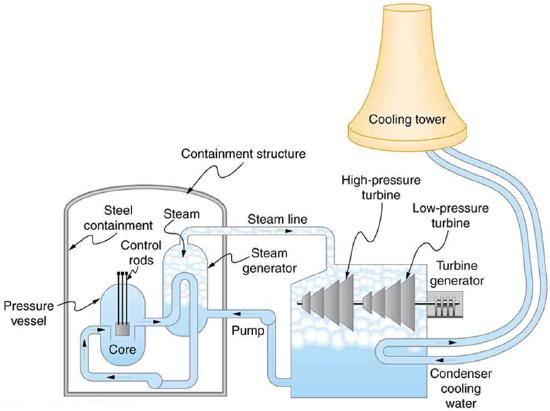

A nuclear power reactor has pressurized water at 300oC. (Higher temperatures are theoretically possible but practically not, due to limitations with materials used in the reactor.) Heat transfer from this water is a complex process (see Figure 15.4.3). Steam, produced in the steam generator, is used to drive the turbine-generators. Eventually the steam is condensed to water at 27oC and then heated again to start the cycle over. Calculate the maximum theoretical efficiency for a heat engine operating between these two temperatures.

Strategy

Since temperatures are given for the hot and cold reservoirs of this heat engine, Effc=1−TcTh can be used to calculate the Carnot (maximum theoretical) efficiency. Those temperatures must first be converted to kelvins.

Solution

The hot and cold reservoir temperatures are given as 300oC and 27oC, respectively. In kelvins, then, Th=573K and Tc=300K, so that the maximum efficiency is Effc=1−TcTh.

Discussion

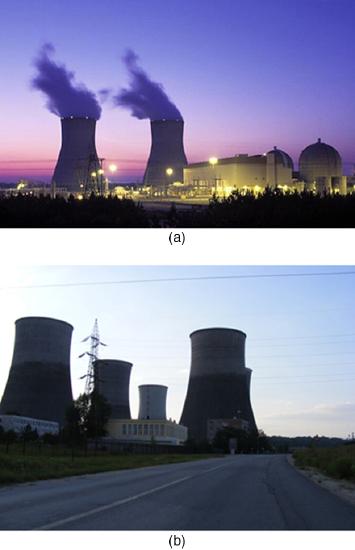

A typical nuclear power station’s actual efficiency is about 35%, a little better than 0.7 times the maximum possible value, a tribute to superior engineering. Electrical power stations fired by coal, oil, and natural gas have greater actual efficiencies (about 42%), because their boilers can reach higher temperatures and pressures. The cold reservoir temperature in any of these power stations is limited by the local environment. Figure 15.4.4 shows (a) the exterior of a nuclear power station and (b) the exterior of a coal-fired power station. Both have cooling towers into which water from the condenser enters the tower near the top and is sprayed downward, cooled by evaporation.

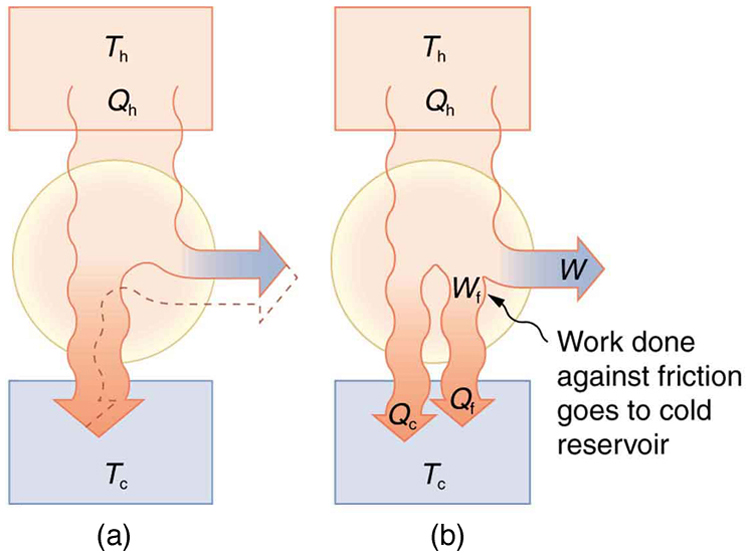

Since all real processes are irreversible, the actual efficiency of a heat engine can never be as great as that of a Carnot engine, as illustrated in Figure 15.4.5(a). Even with the best heat engine possible, there are always dissipative processes in peripheral equipment, such as electrical transformers or car transmissions. These further reduce the overall efficiency by converting some of the engine’s work output back into heat transfer, as shown in Figure 15.4.5(b).

Summary

- The Carnot cycle is a theoretical cycle that is the most efficient cyclical process possible. Any engine using the Carnot cycle, which uses only reversible processes (adiabatic and isothermal), is known as a Carnot engine.

- Any engine that uses the Carnot cycle enjoys the maximum theoretical efficiency.

- While Carnot engines are ideal engines, in reality, no engine achieves Carnot’s theoretical maximum efficiency, since dissipative processes, such as friction, play a role. Carnot cycles without heat loss may be possible at absolute zero, but this has never been seen in nature.

Glossary

- Carnot cycle

- a cyclical process that uses only reversible processes, the adiabatic and isothermal processes

- Carnot engine

- a heat engine that uses a Carnot cycle

- Carnot efficiency

- the maximum theoretical efficiency for a heat engine