5.9: Doppler Effect and Sonic Booms

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

- Define Doppler effect, Doppler shift, and sonic boom.

- Describe the sounds produced by objects moving faster than the speed of sound.

The characteristic sound of a motorcycle buzzing by is an example of the Doppler effect. The high-pitch scream shifts dramatically to a lower-pitch roar as the motorcycle passes by a stationary observer. The closer the motorcycle brushes by, the more abrupt the shift. The faster the motorcycle moves, the greater the shift. We also hear this characteristic shift in frequency for passing race cars, airplanes, and trains. It is so familiar that it is used to imply motion and children often mimic it in play.

The Doppler effect is an alteration in the observed frequency of a sound due to motion of either the source or the observer. Although less familiar, this effect is easily noticed for a stationary source and moving observer. For example, if you ride a train past a stationary warning bell, you will hear the bell’s frequency shift from high to low as you pass by. This change in frequency due to relative motion of source and observer is called a Doppler shift. The Doppler effect is named for the Austrian physicist and mathematician Christian Johann Doppler (1803–1853), who did experiments with both moving sources and moving observers. Doppler, for example, had musicians play on a moving open train car and also play standing next to the train tracks as a train passed by. Their music was observed both on and off the train, and changes in frequency were measured.

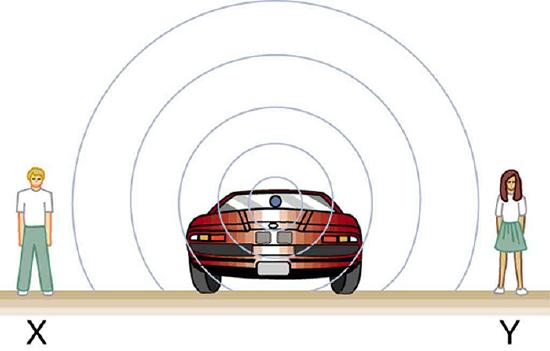

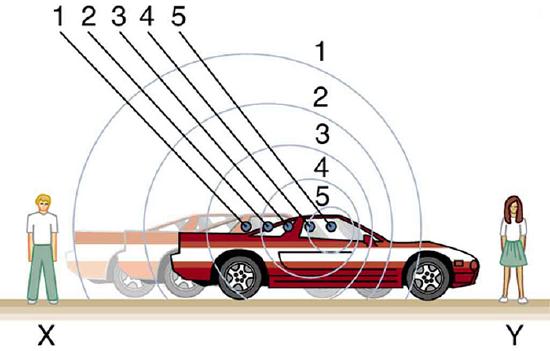

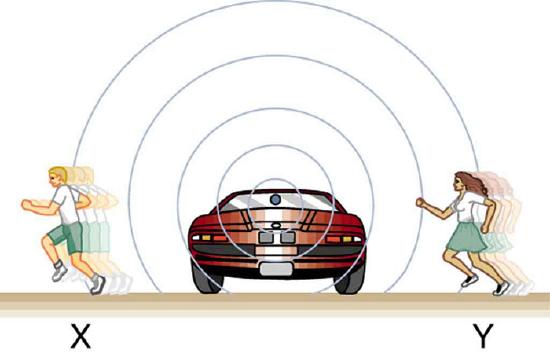

What causes the Doppler shift? Figure 5.9.1, Figure 5.9.2, and Figure 5.9.3 compare sound waves emitted by stationary and moving sources in a stationary air mass. Each disturbance spreads out spherically from the point where the sound was emitted. If the source is stationary, then all of the spheres representing the air compressions in the sound wave centered on the same point, and the stationary observers on either side see the same wavelength and frequency as emitted by the source, as in Figure 5.9.1. If the source is moving, as in Figure 5.9.2, then the situation is different. Each compression of the air moves out in a sphere from the point where it was emitted, but the point of emission moves. This moving emission point causes the air compressions to be closer together on one side and farther apart on the other. Thus, the wavelength is shorter in the direction the source is moving (on the right in Figure 5.9.2), and longer in the opposite direction (on the left in Figure 5.9.2). Finally, if the observers move, as in Figure 5.9.3, the frequency at which they receive the compressions changes. The observer moving toward the source receives them at a higher frequency, and the person moving away from the source receives them at a lower frequency.

We know that wavelength and frequency are related by vw=fλ, where vw is the fixed speed of sound. The sound moves in a medium and has the same speed vw in that medium whether the source is moving or not. Thus f multiplied by λ is a constant. Because the observer on the right in Figure 5.9.2 receives a shorter wavelength, the frequency she receives must be higher. Similarly, the observer on the left receives a longer wavelength, and hence he hears a lower frequency. The same thing happens in Figure 5.9.3. A higher frequency is received by the observer moving toward the source, and a lower frequency is received by an observer moving away from the source. In general, then, relative motion of source and observer toward one another increases the received frequency. Relative motion apart decreases frequency. The greater the relative speed is, the greater the effect.

THE DOPPLER EFFECT

The Doppler effect occurs not only for sound but for any wave when there is relative motion between the observer and the source. There are Doppler shifts in the frequency of sound, light, and water waves, for example. Doppler shifts can be used to determine velocity, such as when ultrasound is reflected from blood in a medical diagnostic. The recession of galaxies is determined by the observed frequency shift of light received from them measured against the frequency emitted by atoms in the laboratory. This implies much about the origins of the universe. Modern physics has been profoundly affected by observations of Doppler shifts.

Sonic Booms to Bow Wakes

What happens to the sound produced by a moving source, such as a jet airplane, that approaches or even exceeds the speed of sound? The answer to this question applies not only to sound but to all other waves as well.

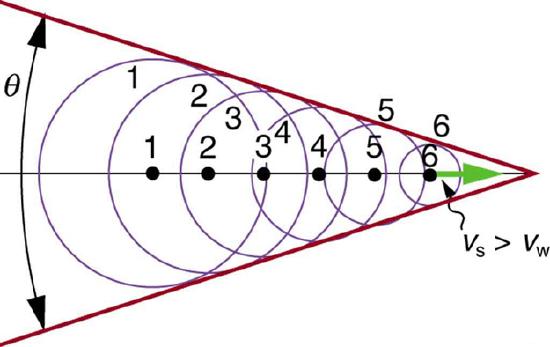

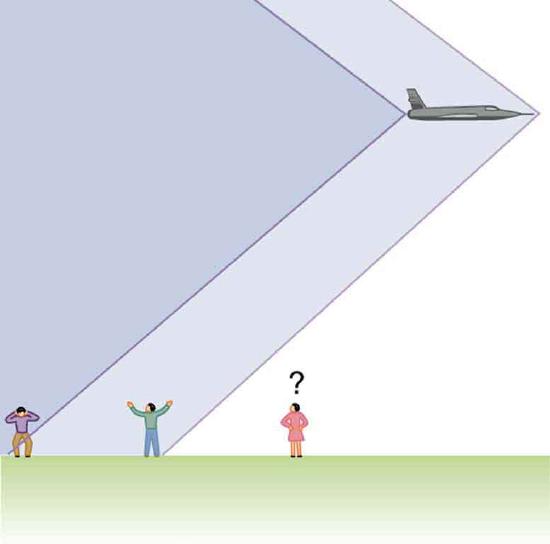

Suppose a jet airplane is coming nearly straight at you, emitting a sound of frequency fs. The greater the plane’s speed vs, the greater the Doppler shift and the greater the value observed for fobs . Now, as vs approaches the speed of sound, fobs approaches infinity. At the speed of sound, this result means that in front of the source, each successive wave is superimposed on the previous one because the source moves forward at the speed of sound. The observer gets them all at the same instant, and so the frequency is infinite. (Before airplanes exceeded the speed of sound, some people argued it would be impossible because such constructive superposition would produce pressures great enough to destroy the airplane.) If the source exceeds the speed of sound, no sound is received by the observer until the source has passed, so that the sounds from the approaching source are mixed with those from it when receding. This mixing appears messy, but something interesting happens—a sonic boom is created. (See Figure 5.9.4.)

There is constructive interference along the lines shown (a cone in three dimensions) from similar sound waves arriving there simultaneously. This superposition forms a disturbance called a sonic boom, a constructive interference of sound created by an object moving faster than sound. Inside the cone, the interference is mostly destructive, and so the sound intensity there is much less than on the shock wave. An aircraft creates two sonic booms, one from its nose and one from its tail. (See Figure 5.9.5.) During television coverage of space shuttle landings, two distinct booms could often be heard. These were separated by exactly the time it would take the shuttle to pass by a point. Observers on the ground often do not see the aircraft creating the sonic boom, because it has passed by before the shock wave reaches them, as seen in Figure 5.9.5. If the aircraft flies close by at low altitude, pressures in the sonic boom can be destructive and break windows as well as rattle nerves. Because of how destructive sonic booms can be, supersonic flights are banned over populated areas of the United States.

Sonic booms are one example of a broader phenomenon called bow wakes. A bow wake, such as the one in Figure 5.9.6, is created when the wave source moves faster than the wave propagation speed. Water waves spread out in circles from the point where created, and the bow wake is the familiar V-shaped wake trailing the source. A more exotic bow wake is created when a subatomic particle travels through a medium faster than the speed of light travels in that medium (the speed of light in vacuum is c=2.998×108 m/s, and this is the maximum speed anything can move, but in water, for example, speed of light slows to 0.75c, and other particles can move faster). If the particle creates light in its passage, that light spreads on a cone with an angle indicative of the speed of the particle, as illustrated in Figure 5.9.7. Such a bow wake is called Cherenkov radiation and is commonly observed in particle physics.

Doppler shifts and sonic booms are interesting sound phenomena that occur in all types of waves. They can be of considerable use. For example, the Doppler shift in ultrasound can be used to measure blood velocity, while police use the Doppler shift in radar (a microwave) to measure car velocities. In meteorology, the Doppler shift is used to track the motion of storm clouds; such “Doppler Radar” can give velocity and direction and rain or snow potential of imposing weather fronts. In astronomy, we can examine the light emitted from distant galaxies and determine their speed relative to ours. As galaxies move away from us, their light is shifted to a lower frequency, and so to a longer wavelength—the so-called red shift. Such information from galaxies far, far away has allowed us to estimate the age of the universe (from the Big Bang) as about 14 billion years.

Exercise 5.9.1

Why did scientist Christian Doppler observe musicians both on a moving train and also from a stationary point not on the train?

- Answer

-

Doppler needed to compare the perception of sound when the observer is stationary and the sound source moves, as well as when the sound source and the observer are both in motion.

Exercise 5.9.2

Describe a situation in your life when you might rely on the Doppler shift to help you either while driving a car or walking near traffic.

- Answer

-

If I am driving and I hear Doppler shift in an ambulance siren, I would be able to tell when it was getting closer and also if it has passed by. This would help me to know whether I needed to pull over and let the ambulance through

- The Doppler shift is change in observed frequency of a wave (for example, a sound wave) due to relative motion of the source and the observer, with approaching source and/or observer increasing the observed frequency and receding source and/or observer decreasing the observed frequency.

- A sonic boom is constructive interference of sound created by an object moving faster than sound.

- A shock wave is a type of bow wake created when any wave source moves faster than the wave propagation speed.

Glossary

- Doppler shift

- the change in wave frequency due to relative motion of source and observer

- sonic boom

- a constructive interference of sound created by an object moving faster than sound

- bow wake

- V-shaped disturbance created when the wave source moves faster than the wave propagation speed