7.5: Pressure Due to the Weight of Fluid

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

- Define pressure in terms of weight.

- Explain the variation of pressure with depth in a fluid.

- Calculate density given pressure and altitude.

If your ears have ever popped on a plane flight or ached during a deep dive in a swimming pool, you have experienced the effect of depth on pressure in a fluid. At the Earth’s surface, the air pressure exerted on you is a result of the weight of air above you. This pressure is reduced as you climb up in altitude and the weight of air above you decreases. Under water, the pressure exerted on you increases with increasing depth. In this case, the pressure being exerted upon you is a result of both the weight of water above you and that of the atmosphere above you. You may notice an air pressure change on an elevator ride that transports you many stories, but you need only dive a meter or so below the surface of a pool to feel a pressure increase. The difference is that water is much denser than air, about 775 times as dense.

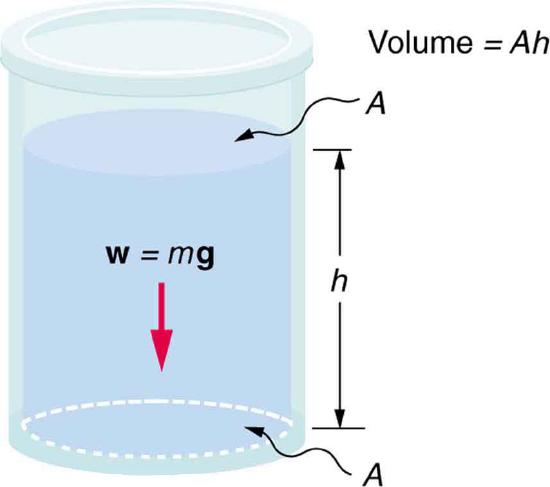

Consider the container in Figure 7.5.1. Its bottom supports the weight of the fluid in it. Let us calculate the pressure exerted on the bottom by the weight of the fluid. That pressure is the weight of the fluid mg divided by the area A supporting it (the area of the bottom of the container):

P=mgA.

We can find the mass of the fluid from its volume and density:

m=ρV.

The volume of the fluid V is related to the dimensions of the container. It is

V=Ah,

where A is the cross-sectional area and h is the depth. Combining the last two equations gives

m=ρAh.

If we enter this into the expression for pressure, we obtain

P=(ρAh)gA.

The area cancels, and rearranging the variables yields

P=ρgh.

This value is the pressure due to the weight of a fluid. The equation has general validity beyond the special conditions under which it is derived here. Even if the container were not there, the surrounding fluid would still exert this pressure, keeping the fluid static. Thus the equation P=ρgh represents the pressure due to the weight of any fluid of average density ρ at any depth h below its surface. For liquids, which are nearly incompressible, this equation holds to great depths.

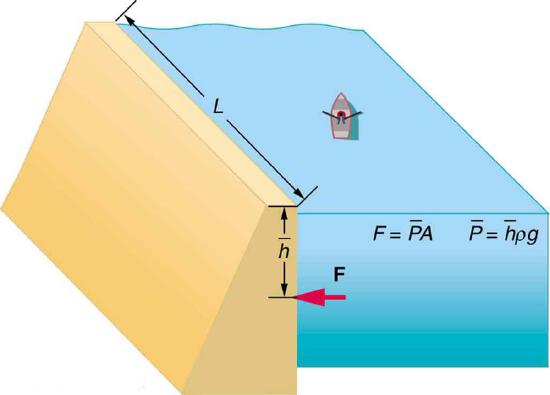

Example 7.5.1: Calculating the Average Pressure and Force Exerted: What Force Must a Dam Withstand?

In Example 8.2.1, we calculated the mass of water in a large reservoir. We will now consider the pressure and force acting on the dam retaining water. (See Figure 7.5.2.) The dam is 500 m wide, and the water is 80.0 m deep at the dam. (a) What is the average pressure on the dam due to the water? (b) Calculate the force exerted against the dam and compare it with the weight of water in the dam (previously found to be 1.96×1013 N).

Strategy for (a)

The average pressure ¯P due to the weight of the water is the pressure at the average depth ˉh of 40.0 m, since pressure increases linearly with depth.

Solution for (a)

The average pressure due to the weight of a fluid is

¯P=ρgˉh.

Entering the density of water from Table 8.2.1 and taking ˉh to be the average depth of 40.0 m, we obtain

¯P=(103kgm3)(9.80ms2)(40.0 m)=3.92×105Nm2=392kPa.

Strategy for (b)

The force exerted on the dam by the water is the average pressure times the area of contact:

F=¯PA

Solution for (b)

We have already found the value for ¯P. The area of the dam is A=80.0 m×500 m=4.00×104 m2, so that

F=(3.92×105 N/m2)(4.00×104 m2)=1.57×1010 N.

Discussion

Although this force seems large, it is small compared with the 1.96×1013 N weight of the water in the reservoir—in fact, it is only 0.0800% of the weight. Note that the pressure found in part (a) is completely independent of the width and length of the lake—it depends only on its average depth at the dam. Thus the force depends only on the water’s average depth and the dimensions of the dam, not on the horizontal extent of the reservoir. In the diagram, the thickness of the dam increases with depth to balance the increasing force due to the increasing pressure.

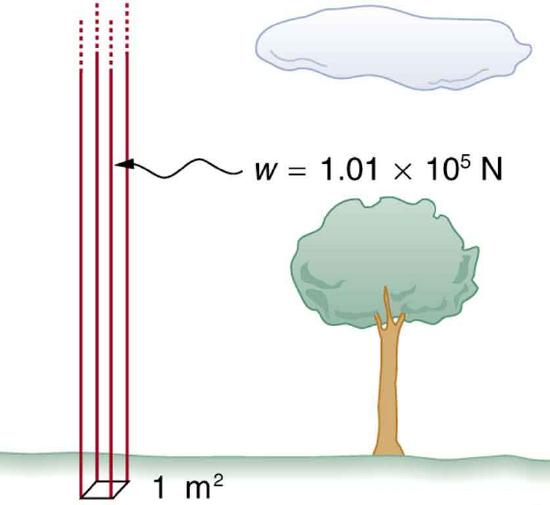

Atmospheric pressure is another example of pressure due to the weight of a fluid, in this case due to the weight of air above a given height. The atmospheric pressure at the Earth’s surface varies a little due to the large-scale flow of the atmosphere induced by the Earth’s rotation (this creates weather “highs” and “lows”). However, the average pressure at sea level is given by the standard atmospheric pressure Patm, measured to be

1 atmosphere (atm)=Patm=1.01×105 N/m2=101 kPa

This relationship means that, on average, at sea level, a column of air above 1.00 m2 of the Earth’s surface has a weight of 1.01×105 N, equivalent to 1 atm. (See Figure 7.5.3.)

Example 7.5.2: Calculating Depth Below the Surface of Water: What Depth of Water Creates the Same Pressure as the Entire Atmosphere?

Calculate the depth below the surface of water at which the pressure due to the weight of the water equals 1.00 atm.

Strategy

We begin by solving the equation P=ρgh for depth h:

h=Pρg.

Then we take P to be 1.00 atm and ρ to be the density of the water that creates the pressure.

Solution

Entering the known values into the expression for h gives

h=1.01×105 N/m2(1.00×103 kg/m3)(9.80 m/s2)=10.3 m.

Discussion

Just 10.3 m of water creates the same pressure as 120 km of air (height of uppermost layers of atmosphere). Since water is nearly incompressible, we can neglect any change in its density over this depth.

What do you suppose is the total pressure at a depth of 10.3 m in a swimming pool? Does the atmospheric pressure on the water’s surface affect the pressure below? The answer is yes. This seems only logical, since both the water’s weight and the atmosphere’s weight must be supported. So the total pressure at a depth of 10.3 m is 2 atm—half from the water above and half from the air above.

Section Summary

- Pressure is the weight of the fluid mg divided by the area A supporting it (the area of the bottom of the container):

P=mgA.

- Pressure due to the weight of a liquid is given by

P=ρgh,

where P is the pressure, ρ is the density of the liquid, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and h is the height of the liquid.

Glossary

- pressure due to the weight of fluid

- pressure at a depth below a fluid surface due to its weight; given by P=ρgh