4.5: Alpha Decay

- Page ID

- 15747

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Many types of heavy atomic nucleus spontaneously decay to produce daughter nucleii via the emission of \(\alpha\)-particles (i.e., helium nucleii) of some characteristic energy. This process is know as \(\alpha\)-decay. Let us investigate the \(\alpha\)-decay of a particular type of atomic nucleus of radius \(R\), charge-number \(Z\), and mass-number \(A\). Such a nucleus thus decays to produce a daughter nucleus of charge-number \(Z_1=Z-2\) and mass-number \(A_1=A-4\), and an \(\alpha\)-particle of charge-number \(Z_2=2\) and mass-number \(A_2=4\). Let the characteristic energy of the \(\alpha\)-particle be \(E\). Incidentally, nuclear radii are found to satisfy the empirical formula \[R = 1.5\times 10^{-15}\,A^{1/3}\,{\rm m}=2.0\times 10^{-15}\,Z_1^{\,1/3}\,{\rm m}\] for \(Z\gg 1\).

In 1928, George Gamow proposed a very successful theory of \(\alpha\)-decay, according to which the \(\alpha\)-particle moves freely inside the nucleus, and is emitted after tunneling through the potential barrier between itself and the daughter nucleus . In other words, the \(\alpha\)-particle, whose energy is \(E\), is trapped in a potential well of radius \(R\) by the potential barrier \[V(r) = \frac{Z_1\,Z_2\,e^{\,2}}{4\pi\,\epsilon_0\,r}\] for \(r>R\).

Making use of the WKB approximation (and neglecting the fact that \(r\) is a radial, rather than a Cartesian, coordinate), the probability of the \(\alpha\)-particle tunneling through the barrier is \[|T|^{\,2} = \exp\left(-\frac{2\sqrt{2\,m}}{\hbar}\int_{r_1}^{r_2} \sqrt{V(r)-E}\,dr\right),\] where \(r_1=R\) and \(r_2 = Z_1\,Z_2\,e^{\,2}/(4\pi\,\epsilon_0\,E)\). Here, \(m=4\,m_p\) is the \(\alpha\)-particle mass. The previous expression reduces to \[|T|^{\,2} = \exp\left(-2\sqrt{2}\,\beta \int_{1}^{E_c/E}\left[\frac{1}{y}-\frac{E}{E_c}\right]^{1/2} dy\right),\] where \[\beta = \left(\frac{Z_1\,Z_2\,e^{\,2}\,m\,R}{4\pi\,\epsilon_0\,\hbar^{\,2}}\right)^{1/2} = 0.74\,Z_1^{\,2/3}\] is a dimensionless constant, and \[E_c = \frac{Z_1\,Z_2\,e^{\,2}}{4\pi\,\epsilon_0\,R} = 1.44\,Z_1^{\,2/3}\,\,{\rm MeV}\] is the characteristic energy the \(\alpha\)-particle would need in order to escape from the nucleus without tunneling. Of course, \(E\ll E_c\). It is easily demonstrated that \[\int_1^{1/\epsilon}\left(\frac{1}{y} - \epsilon\right)^{1/2} dy \simeq \frac{\pi}{2\sqrt{\epsilon}}-2\] when \(\epsilon\ll 1\). Hence. \[|T|^{\,2} \simeq \exp\left(-2\sqrt{2}\,\beta\left[\frac{\pi}{2}\sqrt{\frac{E_c}{E}}-2\right]\right).\]

Now, the \(\alpha\)-particle moves inside the nucleus with the characteristic velocity \(v= \sqrt{2\,E/m}\). It follows that the particle bounces backward and forward within the nucleus at the frequency \(\nu\simeq v/R\), giving \[\nu\simeq 2\times 10^{28}\,\,{\rm yr}^{-1}\] for a 1 MeV \(\alpha\)-particle trapped inside a typical heavy nucleus of radius \(10^{-14}\) m. Thus, the \(\alpha\)-particle effectively attempts to tunnel through the potential barrier \(\nu\) times a second. If each of these attempts has a probability \(|T|^{\,2}\) of succeeding then the probability of decay per unit time is \(\nu\,|T|^{\,2}\). Hence, if there are \(N(t)\gg 1\) undecayed nuclii at time \(t\) then there are only \(N+dN\) at time \(t+dt\), where \[dN = - N\,\nu\,|T|^{\,2}\,dt.\] This expression can be integrated to give \[N(t) = N(0)\,\exp(-\nu\,|T|^{\,2}\,t).\] Now, the half-life, \(\tau\), is defined as the time which must elapse in order for half of the nuclii originally present to decay. It follows from the previous formula that \[\tau = \frac{\ln 2}{\nu\,|T|^{\,2}}.\] Note that the half-life is independent of \(N(0)\).

Finally, making use of the previous results, we obtain \[\label{e5.64} \log_{10}[\tau ({\rm yr})] = -C_1 - C_2\,Z_1^{\,2/3} + C_3\,\frac{Z_1}{\sqrt{E({\rm MeV})}},\] where \[\begin{aligned} C_1 &= 28.5,\\[0.5ex] C_2 &= 1.83,\\[0.5ex] C_3 &= 1.73.\end{aligned}\]

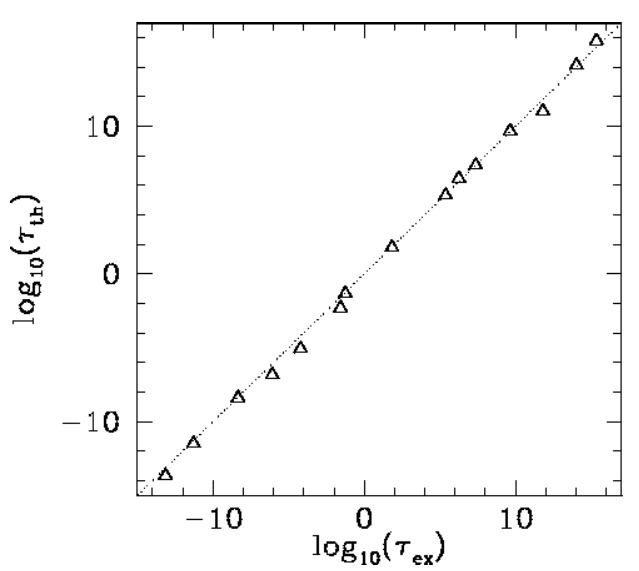

Figure 15: The experimentally determined half-life, \(\begin{equation}\tau_{\mathrm{e} x}\end{equation}\) of various atomic nucleii which decay via ![]() emission versus the best-fit theoretical half-life \(\begin{equation}\log _{10}\left(\tau_{t h}\right)=-28.9-1.60 Z_{1}^{2 / 3}+1.61 Z_{1} / \sqrt{E}\end{equation}\). Both half-lives are measured in years. Here, \(\begin{equation}Z_{1}=Z-2\end{equation}\). Both half-lives are measured in years. Here, \(\begin{equation}Z_{1}=Z-2, \text { where } Z\end{equation}\) is the charge number of the nucleus, and

emission versus the best-fit theoretical half-life \(\begin{equation}\log _{10}\left(\tau_{t h}\right)=-28.9-1.60 Z_{1}^{2 / 3}+1.61 Z_{1} / \sqrt{E}\end{equation}\). Both half-lives are measured in years. Here, \(\begin{equation}Z_{1}=Z-2\end{equation}\). Both half-lives are measured in years. Here, \(\begin{equation}Z_{1}=Z-2, \text { where } Z\end{equation}\) is the charge number of the nucleus, and ![]() the characteristic energy of the emitted

the characteristic energy of the emitted ![]() -particle in MeV. In order of increasing half-life, the points correspond to the following nucleii: Rn 215, Po 214, Po 216, Po 197, Fm 250, Ac 225, U 230, U 232, U 234, Gd 150, U 236, U 238, Pt 190, Gd 152, Nd 144. Data obtained from IAEA Nuclear Data Centre.

-particle in MeV. In order of increasing half-life, the points correspond to the following nucleii: Rn 215, Po 214, Po 216, Po 197, Fm 250, Ac 225, U 230, U 232, U 234, Gd 150, U 236, U 238, Pt 190, Gd 152, Nd 144. Data obtained from IAEA Nuclear Data Centre.

Equation ([e5.64]) is known as the Geiger-Nuttall formula, because it was discovered empirically by H. Geiger and J.M. Nuttall in 1911 .

The half-life, \(\tau\), the daughter charge-number, \(Z_1=Z-2\), and the \(\alpha\)-particle energy, \(E\), for atomic nucleii which undergo \(\alpha\)-decay are indeed found to satisfy a relationship of the form ([e5.64]). The best fit to the data (see Figure [fal]) is obtained using \[\begin{aligned} C_1 &= 28.9,\\[0.5ex] C_2 &= 1.60,\\[0.5ex] C_3 &= 1.61.\end{aligned}\] Note that these values are remarkably similar to those calculated previously.

Contributors and Attributions

Richard Fitzpatrick (Professor of Physics, The University of Texas at Austin)

\( \newcommand {\ltapp} {\stackrel {_{\normalsize<}}{_{\normalsize \sim}}}\) \(\newcommand {\gtapp} {\stackrel {_{\normalsize>}}{_{\normalsize \sim}}}\) \(\newcommand {\btau}{\mbox{\boldmath$\tau$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bmu}{\mbox{\boldmath$\mu$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bsigma}{\mbox{\boldmath$\sigma$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bOmega}{\mbox{\boldmath$\Omega$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bomega}{\mbox{\boldmath$\omega$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bepsilon}{\mbox{\boldmath$\epsilon$}}\)