13.3: Hydrogen Molecule Ion

- Last updated

-

Apr 1, 2025

-

Save as PDF

-

The hydrogen molecule ion consists of an electron orbiting about two protons, and is the simplest imaginable molecule. Let us investigate whether or not this molecule possesses a bound state: that is, whether or not it possesses a ground-state whose energy is less than that of a hydrogen atom and a free proton. According to the variation principle, we can deduce that the H+2 ion has a bound state if we can find any trial wavefunction for which the total Hamiltonian of the system has an expectation value less than that of a hydrogen atom and a free proton.

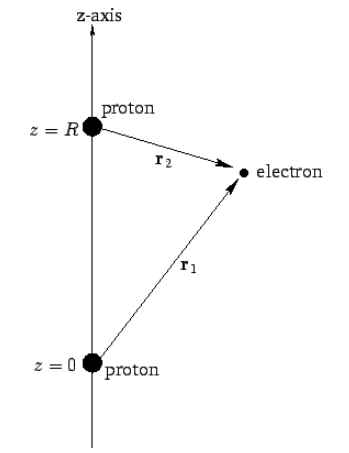

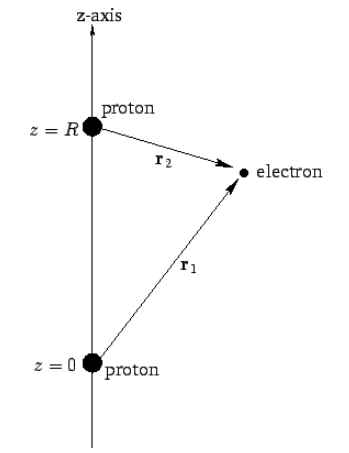

Figure 26: The hydrogen molecule ion.

Suppose that the two protons are separated by a distance R. In fact, let them lie on the z-axis, with the first at the origin, and the second at z=R. See Figure [fh2p]. In the following, we shall treat the protons as essentially stationary. This is reasonable because the electron moves far more rapidly than the protons. Incidentally, the neglect of nuclear motion when calculating the electronic energy of the molecule is known as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

Let us try ψ(r)±=A[ψ0(r1)±ψ0(r2)]

as our trial wavefunction, where ψ0(r)=1√πa3/20e−r/a0

is a normalized hydrogen ground-state wavefunction centered on the origin, and r1,2 are the position vectors of the electron with respect to each of the protons. See Figure [fh2p]. Obviously, this is a very simplistic wavefunction, because it is just a linear combination of hydrogen ground-state wavefunctions centered on each proton . Note, however, that the wavefunction respects the obvious symmetries in the problem.

Our first task is to normalize our trial wavefunction. We require that ∫|ψ±|2d3r=1.

Hence, from Equation ([e14.57]), A=I−1/2, where I=∫[|ψ0(r1)|2+|ψ0(r2)|2±2ψ0(r1)ψ(r2)]d3r.

It follows that I=2(1±J),

with J=∫ψ0(r1)ψ0(r2)d3r.

Let us employ the standard spherical coordinates ( r, θ, ϕ). Now, it is easily seen that r1=r and r2=(r2+R2−2rRcosθ)1/2. Hence, J=2∫∞0∫π0exp[−x−(x2+X2−2xXcosθ)1/2]x2dxsinθdθ,

where X=R/a0. Here, we have already performed the trivial ϕ integral. Let y=(x2+X2−2xXcosθ)1/2. It follows that d(y2)=2ydy=2xXsinθdθ, giving ∫π0e(x2+X2−2xXcosθ)1/2sinθdθ=1xX∫x+X|x−X|e−yydy=−1xX[e−(x+X)(1+x+X)−e−|x−X|(1+|x−X|)].

Thus, J=−2Xe−X∫X0[e−2x(1+X+x)−(1+X−x)]xdx=−2X∫∞Xe−2x[e−X(1+X+x)−eX(1−X+x)]xdx,

which evaluates to J=e−X(1+X+X33).

Now, the Hamiltonian of the electron is written H=−ℏ22me∇2−e24πϵ0(1r1+1r2).

Note, however, that (−ℏ22me∇2−e24πϵ0r1,2)ψ0(r1,2)=E0ψ0(r1,2),

because ψ0(r1,2) are hydrogen ground-state wavefunctions. It follows that Hψ±=A[−ℏ22me∇2−e24πϵ0(1r1+1r2)][ψ0(r1)±ψ0(r2)]=E0ψ−A(e24πϵ0)[ψ0(r1)r2±ψ0(r2)r1].

Hence, ⟨H⟩=E0+4A2(D±E)E0,

where D=⟨ψ0(r1)|a0r2|ψ0(r1)⟩,E=⟨ψ0(r1)|a0r1|ψ0(r2)⟩.

Now, D=2∫∞0∫π0e−2x(x2+X2−2xXcosθ)1/2x2dxsinθdθ,

which reduces to D=4X∫X0e−2xx2dx+4∫∞Xe−2xxdx,

giving

D=1X(1−[1+X]e−2X).

Furthermore, E=2∫∞0∫π0exp[−x−(x2+X2−2xXcosθ)1/2]xdxsinθdθ,

which reduces to E=−2Xe−X∫X0[e−2x(1+X+x)−(1+X−x)]dx=−2X∫∞Xe−2x[e−X(1+X+x)−eX(1−X+x)]dx,

yielding

E=(1+X)e−X.

Our expression for the expectation value of the electron Hamiltonian is ⟨H⟩=[1+2(D±E)(1±J)]E0,

where J, D, and E are specified as functions of X=R/a0 in Equations ([e14.66]), ([e14.75]), and ([e14.78]), respectively. In order to obtain the total energy of the molecule, we must add to this the potential energy of the two protons. Thus, Etotal=⟨H⟩+e24πϵ0R=⟨H⟩−2XE0,

because E0=−e2/(8πϵ0a0). Hence, we can write

Etotal=−F±(R/a0)E0,

where E0 is the hydrogen ground-state energy, and F±(X)=−1+2X[(1+X)e−2X±(1−2X2/3)e−X1±(1+X+X2/3)e−X].

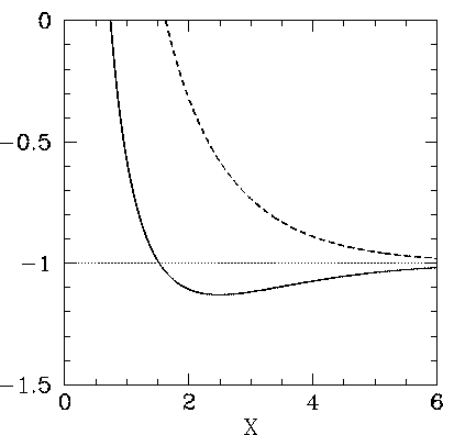

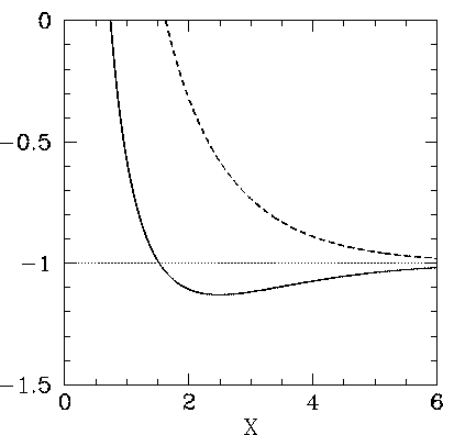

The functions F+(X) and F−(X) are both plotted in Figure [fh2pa]. Recall that in order for the H+2 ion to be in a bound state it must have a lower energy than a hydrogen atom and a free proton: that is, Etotal<E0. It follows from Equation ([e14.81]) that a bound state corresponds to F±<−1. Clearly, the even trial wavefunction ψ+ possesses a bound state, whereas the odd trial wavefunction ψ− does not. [See Equation ([e14.57]).] This is hardly surprising, because the even wavefunction maximizes the electron probability density between the two protons, thereby reducing their mutual electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, the odd wavefunction does exactly the opposite. The binding energy of the H+2 ion is defined as the difference between its energy and that of a hydrogen atom and a free proton: that is, Ebind=Etotal−E0=−(F++1)E0.

According to the variational principle, the binding energy is less than or equal to the minimum binding energy that can be inferred from Figure [fh2pa]. This minimum occurs when X≃2.5 and F+≃−1.13. Thus, our estimates for the separation between the two protons, and the binding energy, for the H+2 ion are R=2.5a0=1.33×10−10m and Ebind=0.13E0=−1.77 eV, respectively. The experimentally determined values are R=1.06×10−10 m, and Ebind=−2.8 eV, respectively . Clearly, our estimates are not particularly accurate. However, our calculation does establish, beyond any doubt, the existence of a bound state of the H+2 ion, which is all that we set out to achieve.

Figure 27: The functions F+(X) (solid curve) and F−(X) (dashed curve).

Contributors and Attributions