9.9: Angular Momentum

- Page ID

- 68835

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe the vector nature of angular momentum

- Find the total angular momentum and torque about a designated origin of a system of particles

- Calculate the angular momentum of a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis

- Calculate the torque on a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis

- Use conservation of angular momentum in the analysis of objects that change their rotation rate

Why does Earth keep on spinning? What started it spinning to begin with? Why doesn’t Earth’s gravitational attraction not bring the Moon crashing in toward Earth? And how does an ice skater manage to spin faster and faster simply by pulling her arms in? Why does she not have to exert a torque to spin faster?

The answer to these questions is that just as the total linear motion (momentum) in the universe is conserved, so is the total rotational motion conserved. We call the total rotational motion angular momentum, the rotational counterpart to linear momentum. In this chapter, we first define and then explore angular momentum from a variety of viewpoints. First, however, we investigate the angular momentum of a single particle. This allows us to develop angular momentum for a system of particles and for a rigid body.

Angular Momentum of a Single Particle

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows a particle at a position \(\vec{r}\) with linear momentum \(\vec{p}\) = m\(\vec{v}\) with respect to the origin. Even if the particle is not rotating about the origin, we can still define an angular momentum in terms of the position vector and the linear momentum.

The angular momentum \(\vec{l}\) of a particle is defined as the cross-product of \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{p}\), and is perpendicular to the plane containing \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{p}\):

\[\vec{l} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p} \ldotp \label{11.5}\]

The intent of choosing the direction of the angular momentum to be perpendicular to the plane containing \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{p}\) is similar to choosing the direction of torque to be perpendicular to the plane of \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{F}\), as discussed in Fixed-Axis Rotation. The magnitude of the angular momentum is found from the definition of the cross-product,

\[l = rp \sin \theta,\]

where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{p}\). The units of angular momentum are kg • m2/s. As with the definition of torque, we can define a lever arm \(r_\perp\) that is the perpendicular distance from the momentum vector \(\vec{p}\) to the origin, \(r_\perp = r \sin \theta\). With this definition, the magnitude of the angular momentum becomes

\[l = r_{\perp} p = r_{\perp} mv \ldotp\]

We see that if the direction of \(\vec{p}\) is such that it passes through the origin, then \(\theta\) = 0, and the angular momentum is zero because the lever arm is zero. In this respect, the magnitude of the angular momentum depends on the choice of origin. If we take the time derivative of the angular momentum, we arrive at an expression for the torque on the particle:

\[ \begin{align*} \frac{d \vec{l}}{dt} &= \frac{d \vec{r}}{dt} \times \vec{p} + \vec{r} \times \frac{d \vec{p}}{dt} \\[4pt] &= \vec{v} \times m \vec{v} + \vec{r} \times \frac{d \vec{p}}{dt} \\[4pt] &= \vec{r} \times \frac{d \vec{p}}{dt} \ldotp \end{align*}\]

Here we have used the definition of \(\vec{p}\) and the fact that a vector crossed into itself is zero. From Newton’s second law \(\frac{d \vec{p}}{dt} = \sum \vec{F}\), the net force acting on the particle, and the definition of the net torque, we can write

\[\frac{d \vec{l}}{dt} = \sum \vec{\tau} \ldotp \label{11.6}\]

Note the similarity with the linear result of Newton’s second law, \(\frac{d \vec{p}}{dt} = \sum \vec{F}\). The following problem-solving strategy can serve as a guideline for calculating the angular momentum of a particle.

- Choose a coordinate system about which the angular momentum is to be calculated.

- Write down the radius vector to the point particle in unit vector notation.

- Write the linear momentum vector of the particle in unit vector notation.

- Take the cross product \(\vec{l} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}\) and use the right-hand rule to establish the direction of the angular momentum vector.

- See if there is a time dependence in the expression of the angular momentum vector. If there is, then a torque exists about the origin, and use \(\frac{d \vec{l}}{dt} = \sum \vec{\tau}\) to calculate the torque. If there is no time dependence in the expression for the angular momentum, then the net torque is zero.

A meteor enters Earth’s atmosphere (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) and is observed by someone on the ground before it burns up in the atmosphere. The vector \(\vec{r}\) = 25 km \(\hat{i}\) + 25 km \(\hat{j}\) gives the position of the meteor with respect to the observer. At the instant the observer sees the meteor, it has linear momentum \(\vec{p}\) = (15.0 kg)(-2.0 km/s \(\hat{j}\)), and it is accelerating at a constant 2.0 m/s2 (\(- \hat{j}\)) along its path, which for our purposes can be taken as a straight line.

- What is the angular momentum of the meteor about the origin, which is at the location of the observer?

- What is the torque on the meteor about the origin?

- Strategy

-

We resolve the acceleration into x- and y-components and use the kinematic equations to express the velocity as a function of acceleration and time. We insert these expressions into the linear momentum and then calculate the angular momentum using the cross-product. Since the position and momentum vectors are in the xy-plane, we expect the angular momentum vector to be along the z-axis. To find the torque, we take the time derivative of the angular momentum.

- Solution

-

The meteor is entering Earth’s atmosphere at an angle of 90.0° below the horizontal, so the components of the acceleration in the x- and y-directions are

\[a_{x} = 0,\; a_{y} = -2.0\; m/s^{2} \ldotp \nonumber\]

We write the velocities using the kinematic equations.

\[v_{x} = 0,\; v_{y} = (-2.0 \times 10^{3}\; m/s) - (2.0\; m/s^{2})t \ldotp \nonumber\]

- The angular momentum is \[\begin{split} \vec{l} & = \vec{r} \times \vec{p} = (25.0\; km\; \hat{i} + 25.0\; km\; \hat{j}) \times (15.0\; kg)(0 \hat{i} + v_{y} \hat{j}) \\ & = 15.0\; kg [ 25.0\; km (v_{y}) \hat{k}] \\ & = 15.0\; kg \{ (2.50 \times 10^{4}\; m)[(-2.0 \times 10^{3}\; m/s) - (2.0\; m/s^{2})t] \hat{k} \} \ldotp \end{split} \nonumber\] At t = 0, the angular momentum of the meteor about the origin is \[\vec{l}_{0} = 15.0\; kg [ (2.50 \times 10^{4}\; m)(-2.0 \times 10^{3}\; m/s) \hat{k}] = 7.50 \times 10^{8}\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s (- \hat{k}) \ldotp \nonumber\] This is the instant that the observer sees the meteor.

- To find the torque, we take the time derivative of the angular momentum. Taking the time derivative of \(\vec{l}\) as a function of time, which is the second equation immediately above, we have \[\frac{d \vec{l}}{dt} = (-15.0\; kg)(2.50 \times 10^{4}\; m)(2.0\; m/s^{2}) \hat{k} \ldotp \nonumber\] Then, since \(\frac{d \vec{l}}{dt} = \sum \vec{\tau}\), we have \[\sum \vec{\tau} = -7.5 \times 10^{5}\; N\; \cdotp m\; \hat{k} \ldotp \nonumber\] The units of torque are given as newton-meters, not to be confused with joules. As a check, we note that the lever arm is the x-component of the vector \(\vec{r}\) in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) since it is perpendicular to the force acting on the meteor, which is along its path. By Newton’s second law, this force is \(\vec{F} = ma (- \hat{j}) = (15.0\; kg)(2.0\; m/s^{2})(- \hat{j}) = 30.0\; kg\; \cdotp m/s^{2} (- \hat{j}) \ldotp\) The lever arm is \(\vec{r}_{\perp} = 2.5 \times 10^{4}\; m\; \hat{i} \ldotp\) Thus, the torque is \(\begin{split} \sum \vec{\tau} = \vec{r}_{\perp} \times \vec{F} & = (2.5 \times 10^{4}\; m\; \hat{i}) \times (-30.0\; kg\; \cdotp m/s^{2}\; \hat{j}), \\ & = 7.5 \times 10^{5}\; N\; \cdotp m (- \hat{k}) \ldotp \end{split}\)

- Significance

-

Since the meteor is accelerating downward toward Earth, its radius and velocity vector are changing. Therefore, since \(\vec{l} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}\), the angular momentum is changing as a function of time. The torque on the meteor about the origin, however, is constant, because the lever arm \(\vec{r}_{\perp}\) and the force on the meteor are constants. This example is important in that it illustrates that the angular momentum depends on the choice of origin about which it is calculated. The methods used in this example are also important in developing angular momentum for a system of particles and for a rigid body.

A proton spiraling around a magnetic field executes circular motion in the plane of the paper, as shown below. The circular path has a radius of 0.4 m and the proton has velocity 4.0 x 106 m/s. What is the angular momentum of the proton about the origin?

Angular Momentum of a System of Particles

The angular momentum of a system of particles is important in many scientific disciplines, one being astronomy. Consider a spiral galaxy, a rotating island of stars like our own Milky Way. The individual stars can be treated as point particles, each of which has its own angular momentum. The vector sum of the individual angular momenta give the total angular momentum of the galaxy. In this section, we develop the tools with which we can calculate the total angular momentum of a system of particles.

In the preceding section, we introduced the angular momentum of a single particle about a designated origin. The expression for this angular momentum is \(\vec{l} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}\), where the vector \(\vec{r}\) is from the origin to the particle, and \(\vec{p}\) is the particle’s linear momentum. If we have a system of N particles, each with position vector from the origin given by \(\vec{r}_{i}\) and each having momentum \(\vec{p}_{i}\), then the total angular momentum of the system of particles about the origin is the vector sum of the individual angular momenta about the origin. That is,

\[\vec{L} = \vec{l}_{1} + \vec{l}_{2} + \cdots + \vec{l}_{N} \ldotp \label{11.7}\]

Similarly, if particle i is subject to a net torque \(\vec{\tau_{i}}\) about the origin, then we can find the net torque about the origin due to the system of particles by differentiating Equation 11.7:

\[\frac{d \vec{L}}{dt} = \sum_{i} \frac{d \vec{l}_{i}}{dt} = \sum_{i} \tau_{i} \ldotp\]

The sum of the individual torques produces a net external torque on the system, which we designate \(\sum \vec{\tau}\). Thus,

\[\frac{d \vec{L}}{dt} = \sum_{i} \tau_{i} \ldotp \label{11.8}\]

Equation \ref{11.8} states that the rate of change of the total angular momentum of a system is equal to the net external torque acting on the system when both quantities are measured with respect to a given origin. Equation \ref{11.8} can be applied to any system that has net angular momentum, including rigid bodies, as discussed in the next section.

Referring to Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\):

- Determine the total angular momentum due to the three particles about the origin.

- What is the rate of change of the angular momentum?

- Strategy

-

Write down the position and momentum vectors for the three particles. Calculate the individual angular momenta and add them as vectors to find the total angular momentum. Then do the same for the torques.

- Solution

-

- Particle 1: \(\vec{r}_{1} = -2.0\; m\; \hat{i} + 1.0\; m\; \hat{j},\; \vec{p}_{1} = (2.0 \; kg)(4.0\; m/s\; \hat{j}) = 8.0\; kg\; \cdotp m/s \; \hat{j},\) \(\vec{l}_{1} = \vec{r}_{1} \times \vec{p}_{1} = -16.0\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s\; \hat{k} \ldotp\) Particle 2: \(\vec{r}_{2} = 4.0\; m \; \hat{i} + 1.0\; m\; \hat{j},\; \vec{p}_{2} = (4.0\; kg)(5.0\; m/s\; \hat{i}) = 20.0\; kg\; \cdotp m/s\; \hat{i},\) \(\vec{l}_{2} = \vec{r}_{2} \times \vec{p}_{2} = -20.0\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s\; \hat{k} \ldotp\) Particle 3: \(\vec{r}_{3} = 2.0\; m\; \hat{i} - 2.0\; m\; \hat{j},\; \vec{p}_{3} = (1.0\; kg)(3.0\; m/s\; \hat{i}) = 3.0\; kg\; \cdotp m/s\; \hat{j},\) \(\vec{l}_{3} = \vec{r}_{3} \times \vec{p}_{3} = 6.0\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s\; \hat{k} \ldotp\) We add the individual angular momenta to find the total about the origin: \(\vec{l}_{T} = \vec{l}_{1} + \vec{l}_{2} + \vec{l}_{3} = -30\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s\; \hat{k} \ldotp\)

- The individual forces and lever arms are \(\begin{split} \vec{r}_{1 \perp} & = 1.0\; m\; \hat{j}, \; \vec{F}_{1} = -6.0\; N\; \hat{i},\; \vec{\tau}_{1} = 6.0\; N\; \cdotp m\; \hat{k} \\ \vec{r}_{2 \perp} & = 4.0\; m\; \hat{i}, \; \vec{F}_{2} = 10.0\; N\; \hat{i},\; \vec{\tau}_{2} = 40.0\; N\; \cdotp m\; \hat{k} \\ \vec{r}_{3 \perp} & = 2.0\; m\; \hat{j}, \; \vec{F}_{3} = -8.0\; N\; \hat{j},\; \vec{\tau}_{3} = -16.0\; N\; \cdotp m\; \hat{k} \ldotp \end{split}\) Therefore: \(\sum_{i} \vec{\tau}_{i} = \vec{\tau}_{1} + \vec{\tau}_{2} + \vec{\tau}_{3} = 30\; N\; \cdotp m\; \hat{k} \ldotp\)

- Significance

-

This example illustrates the superposition principle for angular momentum and torque of a system of particles. Care must be taken when evaluating the radius vectors \(\vec{r}_{i}\) of the particles to calculate the angular momenta, and the lever arms, \(\vec{r}_{i \perp}\) to calculate the torques, as they are completely different quantities.

Angular Momentum of a Rigid Body

We have investigated the angular momentum of a single particle, which we generalized to a system of particles. Now we can use the principles discussed in the previous section to develop the concept of the angular momentum of a rigid body. Celestial objects such as planets have angular momentum due to their spin and orbits around stars. In engineering, anything that rotates about an axis carries angular momentum, such as flywheels, propellers, and rotating parts in engines. Knowledge of the angular momenta of these objects is crucial to the design of the system in which they are a part.

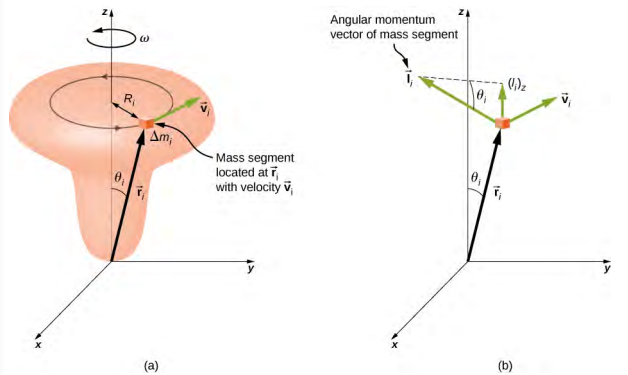

To develop the angular momentum of a rigid body, we model a rigid body as being made up of small mass segments, \(\Delta\)mi. In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), a rigid body is constrained to rotate about the z-axis with angular velocity \(\omega\). All mass segments that make up the rigid body undergo circular motion about the z-axis with the same angular velocity. Part (a) of the figure shows mass segment \(\Delta\)mi with position vector \(\vec{r}_{i}\) from the origin and radius Ri to the z-axis. The magnitude of its tangential velocity is vi = Ri\(\omega\). Because the vectors \(\vec{v}_{i}\) and \(\vec{r}_{i}\) are perpendicular to each other, the magnitude of the angular momentum of this mass segment is

\[l_{i} = r_{i} (\Delta mv_{i}) \sin 90^{o} \ldotp\]

Using the right-hand rule, the angular momentum vector points in the direction shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4b}\). The sum of the angular momenta of all the mass segments contains components both along and perpendicular to the axis of rotation. Every mass segment has a perpendicular component of the angular momentum that will be cancelled by the perpendicular component of an identical mass segment on the opposite side of the rigid body. Thus, the component along the axis of rotation is the only component that gives a nonzero value when summed over all the mass segments. From part (b), the component of \(\vec{l}_{i}\) along the axis of rotation is

\[\begin{split} (l_{i})_{z} & = l_{i} \sin \theta_{i} = (r_{i} \Delta m_{i} v_{i}) \sin \theta_{i}, \\ & = (r_{i} \sin \theta_{i})(\Delta m_{i} v_{i}) = R_{i} \Delta m_{i} v_{i} \ldotp \end{split}\]

The net angular momentum of the rigid body along the axis of rotation is

\[L = \sum_{i} (\vec{l}_{i})_{z} = \sum_{i} R_{i} \Delta m_{i} v_{i} = \sum_{i} R_{i} \Delta m_{i} (R_{i} \omega) = \omega \sum_{i} \Delta m_{i} (R_{i})^{2} \ldotp\]

The summation \(\sum_{i} \Delta\)(Ri)2 is simply the moment of inertia I of the rigid body about the axis of rotation. For a thin hoop rotating about an axis perpendicular to the plane of the hoop, all of the Ri’s are equal to R so the summation reduces to R2\(\sum_{i} \Delta\)mi = mR2, which is the moment of inertia for a thin hoop found in Figure 10.20. Thus, the magnitude of the angular momentum along the axis of rotation of a rigid body rotating with angular velocity \(\omega\) about the axis is

\[L = I \omega \ldotp \label{11.9}\]

This equation is analogous to the magnitude of the linear momentum p = mv. The direction of the angular momentum vector is directed along the axis of rotation given by the right-hand rule.

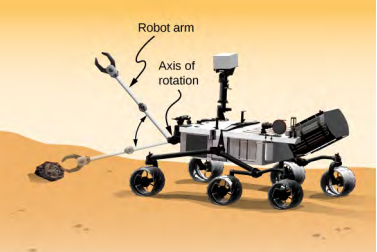

A robot arm on a Mars rover like Curiosity shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) is 1.0 m long and has forceps at the free end to pick up rocks. The mass of the arm is 2.0 kg and the mass of the forceps is 1.0 kg (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). The robot arm and forceps move from rest to \(\omega\) = 0.1\(\pi\) rad/s in 0.1 s. It rotates down and picks up a Mars rock that has mass 1.5 kg. The axis of rotation is the point where the robot arm connects to the rover.

- What is the angular momentum of the robot arm by itself about the axis of rotation after 0.1 s when the arm has stopped accelerating?

- What is the angular momentum of the robot arm when it has the Mars rock in its forceps and is rotating upwards?

- When the arm does not have a rock in the forceps, what is the torque about the point where the arm connects to the rover when it is accelerating from rest to its final angular velocity?

- Strategy

-

We use Equation \ref{11.9} to find angular momentum in the various configurations. When the arm is rotating downward, the right-hand rule gives the angular momentum vector directed out of the page, which we will call the positive z-direction. When the arm is rotating upward, the right-hand rule gives the direction of the angular momentum vector into the page or in the negative z-direction. The moment of inertia is the sum of the individual moments of inertia. The arm can be approximated with a solid rod, and the forceps and Mars rock can be approximated as point masses located at a distance of 1 m from the origin. For part (c), we use Newton’s second law of motion for rotation to find the torque on the robot arm.

- Solution

-

- Writing down the individual moments of inertia, we have

- Robot arm: \[I_{R} = \frac{1}{3} m_{R} r^{2} = \frac{1}{3} (2.00\; kg)(1.00\; m)^{2} = \frac{2}{3}\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2} \ldotp\]

- Forceps: \[I_{F} = m_{F} r^{2} = (1.0\; kg)(1.0\; m)^{2} = 1.0\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2} \ldotp\]

- Mars rock: \[I_{MR} = m_{MR} r^{2} = (1.5\; kg)(1.0\; m)^{2} = 1.5\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2} \ldotp\]

Therefore, without the Mars rock, the total moment of inertia is

\[I_{Total} = I_{R} + I_{F} = 1.67\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}\]

and the magnitude of the angular momentum is

\[L = I \omega = (1.67\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2})(0.1 \pi\; rad/s) = 0.17 \pi\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s \ldotp\]

The angular momentum vector is directed out of the page in the \(\hat{k}\) direction since the robot arm is rotating counterclockwise.

- We must include the Mars rock in the calculation of the moment of inertia, so we have \[I_{Total} = I_{R} + I_{F} + I_{MR} = 3.17\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}\] and \[L = I \omega = (3.17\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2})(0.1 \pi\; rad/s) = 0.32 \pi\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2}/s \ldotp\] Now the angular momentum vector is directed into the page in the \(- \hat{k}\) direction, by the right-hand rule, since the robot arm is now rotating clockwise.

- We find the torque when the arm does not have the rock by taking the derivative of the angular momentum using Equation \ref{11.8} \(\frac{d \vec{L}}{dt} = \sum \vec{\tau}\). But since L = I\(\omega\), and understanding that the direction of the angular momentum and torque vectors are along the axis of rotation, we can suppress the vector notation and find \[\frac{dL}{dt} = \frac{d (I \omega)}{dt} = I \frac{d \omega}{dt} = I \alpha = \sum \tau,\] which is Newton’s second law for rotation. Since \(\alpha = \frac{0.1 \pi\; rad/s}{0.1\; s} = \pi\; rad/s^{2}\), we can calculate the net torque: \[\sum \tau = I \alpha = (1.67\; kg\; \cdotp m^{2})(\pi\; rad/s^{2}) = 1.67 \pi\; N\; \cdotp m \ldotp\]

- Significance

-

The angular momentum in (a) is less than that of (b) due to the fact that the moment of inertia in (b) is greater than (a), while the angular velocity is the same.