1.5: The Sky Above

- Page ID

- 44009

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the main features of the celestial sphere

- Explain the system astronomers use to describe the sky

- Describe how motions of the stars appear to us on Earth

- Describe how motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets appear to us on Earth

- Understand the modern meaning of the term constellation

Our senses suggest to us that Earth is the center of the universe—the hub around which the heavens turn. This geocentric (Earth-centered) view was what almost everyone believed until the European Renaissance. After all, it is simple, logical, and seemingly self-evident. Furthermore, the geocentric perspective reinforced those philosophical and religious systems that taught the unique role of human beings as the central focus of the cosmos. However, the geocentric view happens to be wrong. One of the great themes of our intellectual history is the overthrow of the geocentric perspective. Let us, therefore, take a look at the steps by which we reevaluated the place of our world in the cosmic order.

The Celestial Sphere

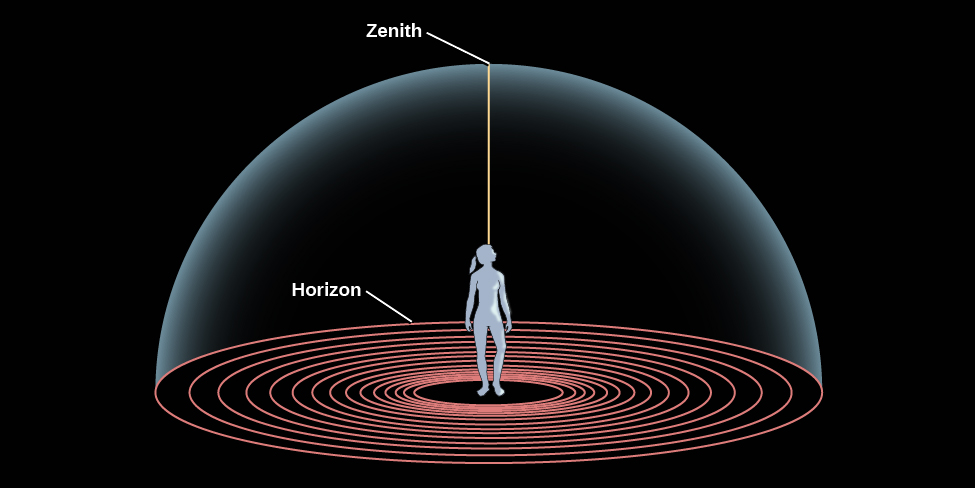

If you go on a camping trip or live far from city lights, your view of the sky on a clear night is pretty much identical to that seen by people all over the world before the invention of the telescope. Gazing up, you get the impression that the sky is a great hollow dome with you at the center (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), and all the stars are an equal distance from you on the surface of the dome. The top of that dome, the point directly above your head, is called the zenith, and where the dome meets Earth is called the horizon. From the sea or a flat prairie, it is easy to see the horizon as a circle around you, but from most places where people live today, the horizon is at least partially hidden by mountains, trees, buildings, or smog.

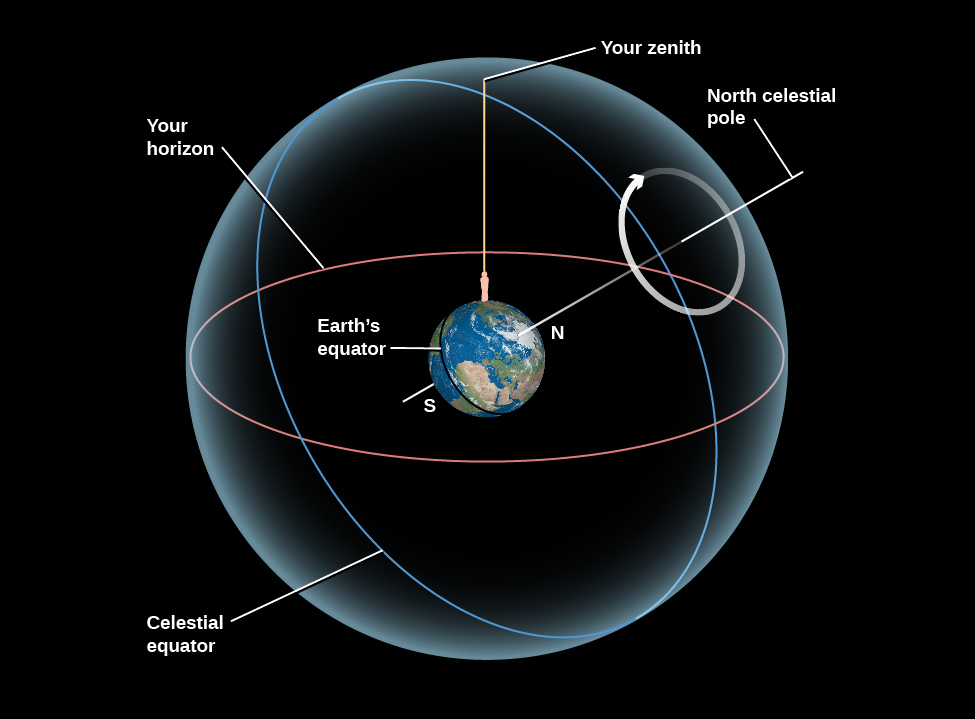

If you lie back in an open field and observe the night sky for hours, as ancient shepherds and travelers regularly did, you will see stars rising on the eastern horizon (just as the Sun and Moon do), moving across the dome of the sky in the course of the night, and setting on the western horizon. Watching the sky turn like this night after night, you might eventually get the idea that the dome of the sky is really part of a great sphere that is turning around you, bringing different stars into view as it turns. The early Greeks regarded the sky as just such a celestial sphere (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Some thought of it as an actual sphere of transparent crystalline material, with the stars embedded in it like tiny jewels.

Today, we know that it is not the celestial sphere that turns as night and day proceed, but rather the planet on which we live. We can put an imaginary stick through Earth’s North and South Poles, representing our planet’s axis. It is because Earth turns on this axis every 24 hours that we see the Sun, Moon, and stars rise and set with clockwork regularity. Today, we know that these celestial objects are not really on a dome, but at greatly varying distances from us in space. Nevertheless, it is sometimes still convenient to talk about the celestial dome or sphere to help us keep track of objects in the sky. There is even a special theater, called a planetarium, in which we project a simulation of the stars and planets onto a white dome.

As the celestial sphere rotates, the objects on it maintain their positions with respect to one another. A grouping of stars such as the Big Dipper has the same shape during the course of the night, although it turns with the sky. During a single night, even objects we know to have significant motions of their own, such as the nearby planets, seem fixed relative to the stars. Only meteors—brief “shooting stars” that flash into view for just a few seconds—move appreciably with respect to other objects on the celestial sphere. (This is because they are not stars at all. Rather, they are small pieces of cosmic dust, burning up as they hit Earth’s atmosphere.) We can use the fact that the entire celestial sphere seems to turn together to help us set up systems for keeping track of what things are visible in the sky and where they happen to be at a given time.

Celestial Poles and Celestial Equator

To help orient us in the turning sky, astronomers use a system that extends Earth’s axis points into the sky. Imagine a line going through Earth, connecting the North and South Poles. This is Earth’s axis, and Earth rotates about this line. If we extend this imaginary line outward from Earth, the points where this line intersects the celestial sphere are called the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole. As Earth rotates about its axis, the sky appears to turn in the opposite direction around those celestial poles (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). We also (in our imagination) throw Earth’s equator onto the sky and call this the celestial equator. It lies halfway between the celestial poles, just as Earth’s equator lies halfway between our planet’s poles.

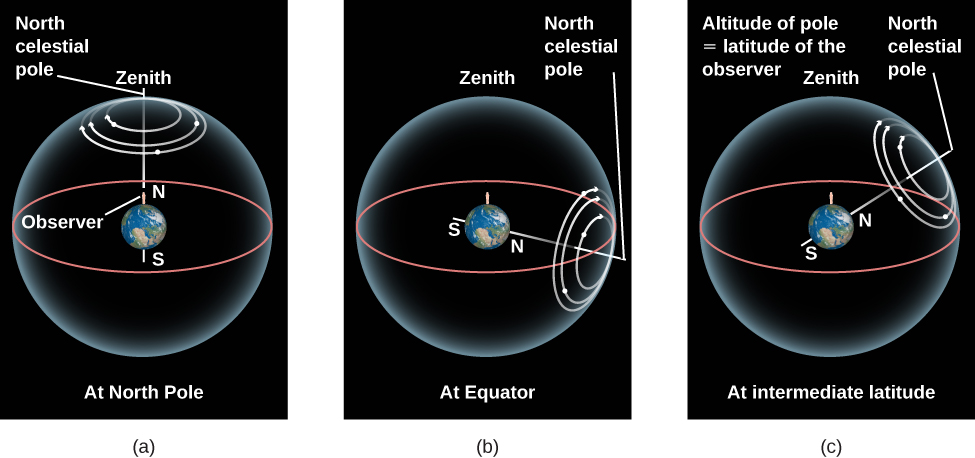

Now let’s imagine how riding on different parts of our spinning Earth affects our view of the sky. The apparent motion of the celestial sphere depends on your latitude (position north or south of the equator). First of all, notice that Earth’s axis is pointing at the celestial poles, so these two points in the sky do not appear to turn.

If you stood at the North Pole of Earth, for example, you would see the north celestial pole overhead, at your zenith. The celestial equator, 90° from the celestial poles, would lie along your horizon. As you watched the stars during the course of the night, they would all circle around the celestial pole, with none rising or setting. Only that half of the sky north of the celestial equator is ever visible to an observer at the North Pole. Similarly, an observer at the South Pole would see only the southern half of the sky.

If you were at Earth’s equator, on the other hand, you see the celestial equator (which, after all, is just an “extension” of Earth’s equator) pass overhead through your zenith. The celestial poles, being 90° from the celestial equator, must then be at the north and south points on your horizon. As the sky turns, all stars rise and set; they move straight up from the east side of the horizon and set straight down on the west side. During a 24-hour period, all stars are above the horizon exactly half the time. (Of course, during some of those hours, the Sun is too bright for us to see them.)

What would an observer in the latitudes of the United States or Europe see? Remember, we are neither at Earth’s pole nor at the equator, but in between them. For those in the continental United States and Europe, the north celestial pole is neither overhead nor on the horizon, but in between. It appears above the northern horizon at an angular height, or altitude, equal to the observer’s latitude. In San Francisco, for example, where the latitude is 38° N, the north celestial pole is 38° above the northern horizon.

For an observer at 38° N latitude, the south celestial pole is 38° below the southern horizon and, thus, never visible. As Earth turns, the whole sky seems to pivot about the north celestial pole. For this observer, stars within 38° of the North Pole can never set. They are always above the horizon, day and night. This part of the sky is called the north circumpolar zone. For observers in the continental United States, the Big Dipper, Little Dipper, and Cassiopeia are examples of star groups in the north circumpolar zone. On the other hand, stars within 38° of the south celestial pole never rise. That part of the sky is the south circumpolar zone. To most U.S. observers, the Southern Cross is in that zone. (Don’t worry if you are not familiar with the star groups just mentioned; we will introduce them more formally later on.)

The Rotating Sky Lab created by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln provides an interactive demonstration that introduces the horizon coordinate system, the apparent rotation of the sky, and allows for exploration of the relationship between the horizon and celestial equatorial coordinate systems.

At this particular time in Earth’s history, there happens to be a star very close to the north celestial pole. It is called Polaris, the pole star, and has the distinction of being the star that moves the least amount as the northern sky turns each day. Because it moved so little while the other stars moved much more, it played a special role in the mythology of several Native American tribes, for example (some called it the “fastener of the sky”).

WHAT’S YOUR ANGLE?

Astronomers measure how far apart objects appear in the sky by using angles. By definition, there are 360° in a circle, so a circle stretching completely around the celestial sphere contains 360°. The half-sphere or dome of the sky then contains 180° from horizon to opposite horizon. Thus, if two stars are 18° apart, their separation spans about 1/10 of the dome of the sky. To give you a sense of how big a degree is, the full Moon is about half a degree across. This is about the width of your smallest finger (pinkie) seen at arm’s length.

Rising and Setting of the Sun

We described the movement of stars in the night sky, but what about during the daytime? The stars continue to circle during the day, but the brilliance of the Sun makes them difficult to see. (The Moon can often be seen in the daylight, however.) On any given day, we can think of the Sun as being located at some position on the hypothetical celestial sphere. When the Sun rises—that is, when the rotation of Earth carries the Sun above the horizon—sunlight is scattered by the molecules of our atmosphere, filling our sky with light and hiding the stars above the horizon.

For thousands of years, astronomers have been aware that the Sun does more than just rise and set. It changes position gradually on the celestial sphere, moving each day about 1° to the east relative to the stars. Very reasonably, the ancients thought this meant the Sun was slowly moving around Earth, taking a period of time we call 1 year to make a full circle. Today, of course, we know it is Earth that is going around the Sun, but the effect is the same: the Sun’s position in our sky changes day to day. We have a similar experience when we walk around a campfire at night; we see the flames appear in front of each person seated about the fire in turn.

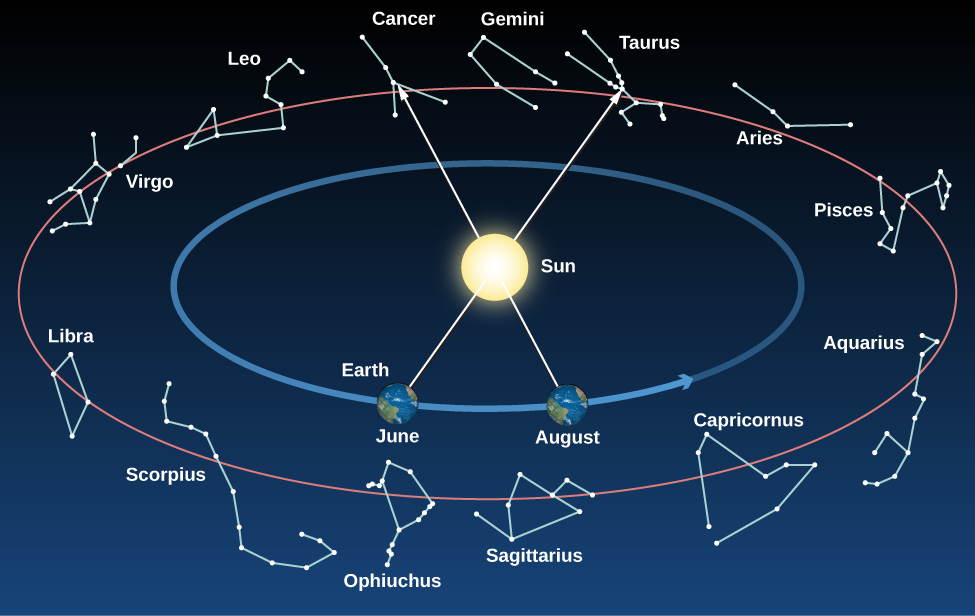

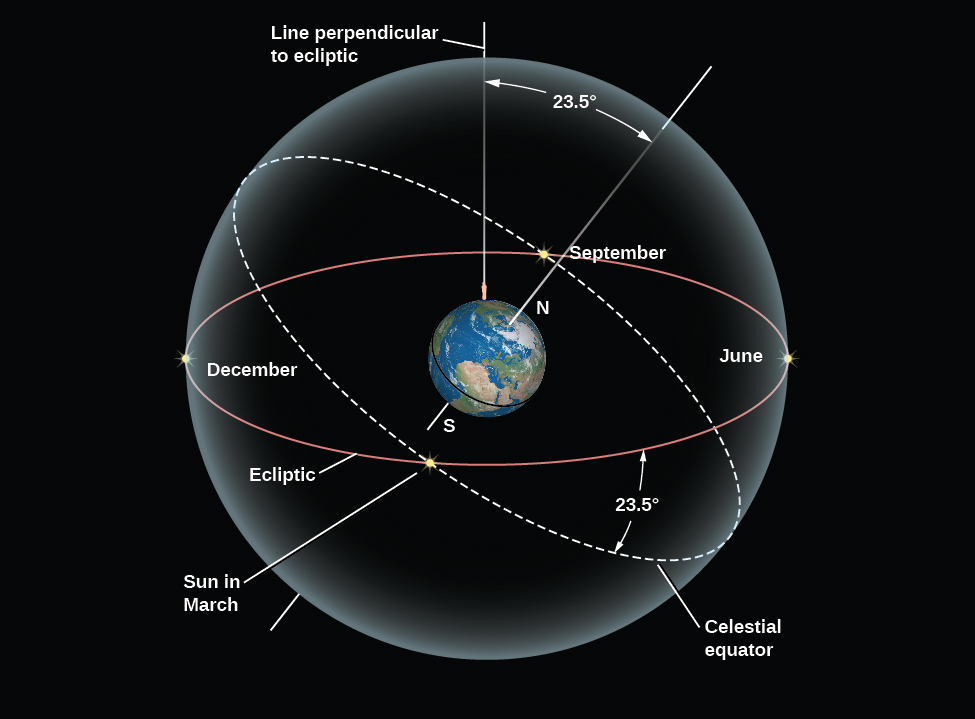

The path the Sun appears to take around the celestial sphere each year is called the ecliptic (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Because of its motion on the ecliptic, the Sun rises about 4 minutes later each day with respect to the stars. Earth must make just a bit more than one complete rotation (with respect to the stars) to bring the Sun up again.

As the months go by and we look at the Sun from different places in our orbit, we see it projected against different places in our orbit, and thus against different stars in the background (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) and Table \(\PageIndex{1}\))—or we would, at least, if we could see the stars in the daytime. In practice, we must deduce which stars lie behind and beyond the Sun by observing the stars visible in the opposite direction at night. After a year, when Earth has completed one trip around the Sun, the Sun will appear to have completed one circuit of the sky along the ecliptic.

| Constellation on the Ecliptic | Dates When the Sun Crosses It |

|---|---|

| Capricornus | January 21–February 16 |

| Aquarius | February 16–March 11 |

| Pisces | March 11–April 18 |

| Aries | April 18–May 13 |

| Taurus | May 13–June 22 |

| Gemini | June 22–July 21 |

| Cancer | July 21–August 10 |

| Leo | August 10–September 16 |

| Virgo | September 16–October 31 |

| Libra | October 31–November 23 |

| Scorpius | November 23–November 29 |

| Ophiuchus | November 29–December 18 |

| Sagittarius | December 18–January 21 |

The ecliptic does not lie along the celestial equator but is inclined to it at an angle of about 23.5°. In other words, the Sun’s annual path in the sky is not linked with Earth’s equator. This is because our planet’s axis of rotation is tilted by about 23.5° from a vertical line sticking out of the plane of the ecliptic (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Being tilted from “straight up” is not at all unusual among celestial bodies; Uranus and Pluto are actually tilted so much that they orbit the Sun “on their side.”

The inclination of the ecliptic is the reason the Sun moves north and south in the sky as the seasons change. In Earth, Moon, and Sky, we discuss the progression of the seasons in more detail.

Fixed and Wandering Stars

The Sun is not the only object that moves among the fixed stars. The Moon and each of the planets that are visible to the unaided eye—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus (although just barely)—also change their positions slowly from day to day. During a single day, the Moon and planets all rise and set as Earth turns, just as the Sun and stars do. But like the Sun, they have independent motions among the stars, superimposed on the daily rotation of the celestial sphere. Noticing these motions, the Greeks of 2000 years ago distinguished between what they called the fixed stars—those that maintain fixed patterns among themselves through many generations—and the wandering stars, or planets. The word “planet,” in fact, means “wanderer” in ancient Greek.

Today, we do not regard the Sun and Moon as planets, but the ancients applied the term to all seven of the moving objects in the sky. Much of ancient astronomy was devoted to observing and predicting the motions of these celestial wanderers. They even dedicated a unit of time, the week, to the seven objects that move on their own; that’s why there are 7 days in a week. The Moon, being Earth’s nearest celestial neighbor, has the fastest apparent motion; it completes a trip around the sky in about 1 month (or moonth). To do this, the Moon moves about 12°, or 24 times its own apparent width on the sky, each day.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Angles in the Sky

A circle consists of 360 degrees (°). When we measure the angle in the sky that something moves, we can use this formula:

\[\text{speed}=\dfrac{\text{distance}}{\text{time}} \nonumber\]

This is true whether the motion is measured in kilometers per hour or degrees per hour; we just need to use consistent units.

As an example, let’s say you notice the bright star Sirius due south from your observing location in the Northern Hemisphere. You note the time, and then later, you note the time that Sirius sets below the horizon. You find that Sirius has traveled an angular distance of about 75° in 5 h. About how many hours will it take for Sirius to return to its original location?

- Answer

-

The speed of Sirius is

\[\dfrac{75°}{5\,h}=\dfrac{15°}{1\,h} \nonumber\]

If we want to know the time required for Sirius to return to its original location, we need to wait until it goes around a full circle, or 360°. Rearranging the formula for speed we were originally given, we find:

\[\text{time}=\dfrac{\text{distance}}{\text{speed}} = \dfrac{360°}{15°/h}=24\,h \nonumber\]

The actual time is a few minutes shorter than this (sidereal day).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The Moon moves in the sky relative to the background stars (in addition to moving with the stars as a result of Earth’s rotation.) Go outside at night and note the position of the Moon relative to nearby stars. Repeat the observation a few hours later. How far has the Moon moved? (For reference, the diameter of the Moon is about 0.5°.) Based on your estimate of its motion, how long will it take for the Moon to return to the position relative to the stars in which you first observed it?

- Answer

-

The speed of the moon is 0.5°/1 h. To move a full 360°, the moon needs 720 h: 0.5°1h=360°720h.0.5°1h=360°720h.

Dividing 720 h by the conversion factor of 24 h/day reveals the lunar cycle is about 30 days.

The individual paths of the Moon and planets in the sky all lie close to the ecliptic, although not exactly on it. This is because the paths of the planets about the Sun, and of the Moon about Earth, are all in nearly the same plane, as if they were circles on a huge sheet of paper. The planets, the Sun, and the Moon are thus always found in the sky within a narrow 18-degree-wide belt, centered on the ecliptic, called the zodiac (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). (The root of the term “zodiac” is the same as that of the word “zoo” and means a collection of animals; many of the patterns of stars within the zodiac belt reminded the ancients of animals, such as a fish or a goat.)

How the planets appear to move in the sky as the months pass is a combination of their actual motions plus the motion of Earth about the Sun; consequently, their paths are somewhat complex. As we will see, this complexity has fascinated and challenged astronomers for centuries.

Constellations

The backdrop for the motions of the “wanderers” in the sky is the canopy of stars. If there were no clouds in the sky and we were on a flat plain with nothing to obstruct our view, we could see about 3000 stars with the unaided eye. To find their way around such a multitude, the ancients found groupings of stars that made some familiar geometric pattern or (more rarely) resembled something they knew. Each civilization found its own patterns in the stars, much like a modern Rorschach test in which you are asked to discern patterns or pictures in a set of inkblots. The ancient Chinese, Egyptians, and Greeks, among others, found their own groupings—or constellations—of stars. These were helpful in navigating among the stars and in passing their star lore on to their children.

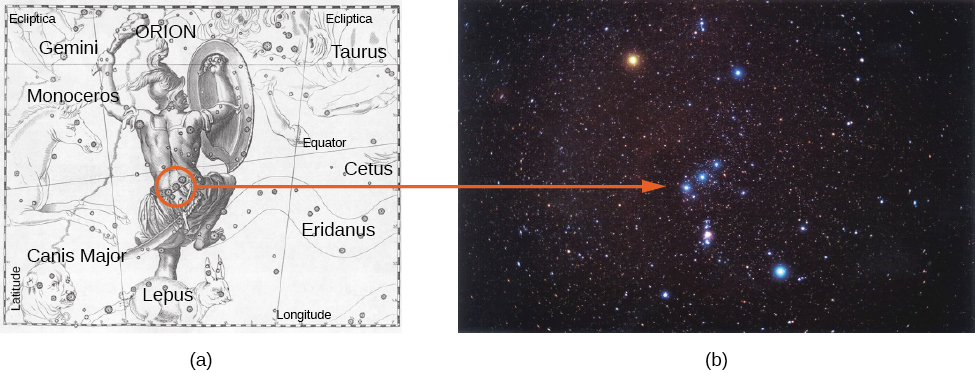

You may be familiar with some of the old star patterns we still use today, such as the Big Dipper, Little Dipper, and Orion the hunter, with his distinctive belt of three stars (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). However, many of the stars we see are not part of a distinctive star pattern at all, and a telescope reveals millions of stars too faint for the eye to see. Therefore, during the early decades of the 20th century, astronomers from many countries decided to establish a more formal system for organizing the sky.

Today, we use the term constellation to mean one of 88 sectors into which we divide the sky, much as the United States is divided into 50 states. The modern boundaries between the constellations are imaginary lines in the sky running north–south and east–west, so that each point in the sky falls in a specific constellation, although, like the states, not all constellations are the same size. All the constellations are listed in Appendix L. Whenever possible, we have named each modern constellation after the Latin translations of one of the ancient Greek star patterns that lies within it. Thus, the modern constellation of Orion is a kind of box on the sky, which includes, among many other objects, the stars that made up the ancient picture of the hunter. Some people use the term asterism to denote an especially noticeable star pattern within a constellation (or sometimes spanning parts of several constellations). For example, the Big Dipper is an asterism within the constellation of Ursa Major, the Big Bear.

Students are sometimes puzzled because the constellations seldom resemble the people or animals for which they were named. In all likelihood, the Greeks themselves did not name groupings of stars because they looked like actual people or subjects (any more than the outline of Washington state resembles George Washington). Rather, they named sections of the sky in honor of the characters in their mythology and then fit the star configurations to the animals and people as best they could.

This website about objects in the sky allows users to construct a detailed sky map showing the location and information about the Sun, Moon, planets, stars, constellations, and even satellites orbiting Earth. Begin by setting your observing location using the option in the menu in the upper right corner of the screen.

The direct evidence of our senses supports a geocentric perspective, with the celestial sphere pivoting on the celestial poles and rotating about a stationary Earth. We see only half of this sphere at one time, limited by the horizon; the point directly overhead is our zenith. The Sun’s annual path on the celestial sphere is the ecliptic—a line that runs through the center of the zodiac, which is the 18-degree-wide strip of the sky within which we always find the Moon and planets. The celestial sphere is organized into 88 constellations, or sectors.

Glossary

- celestial equator

- a great circle on the celestial sphere 90° from the celestial poles; where the celestial sphere intersects the plane of Earth’s equator

- celestial poles

- points about which the celestial sphere appears to rotate; intersections of the celestial sphere with Earth’s polar axis

- celestial sphere

- the apparent sphere of the sky; a sphere of large radius centered on the observer; directions of objects in the sky can be denoted by their position on the celestial sphere

- circumpolar zone

- those portions of the celestial sphere near the celestial poles that are either always above or always below the horizon

- ecliptic

- the apparent annual path of the Sun on the celestial sphere

- geocentric

- centered on Earth

- horizon (astronomical)

- a great circle on the celestial sphere 90° from the zenith; more popularly, the circle around us where the dome of the sky meets Earth

- planet

- today, any of the larger objects revolving about the Sun or any similar objects that orbit other stars; in ancient times, any object that moved regularly among the fixed stars

- zodiac

- a belt around the sky about 18° wide centered on the ecliptic zenith the point on the celestial sphere opposite the direction of gravity; point directly above the observer year the period of revolution of Earth around the Sun

Contributors and Attributions

Andrew Fraknoi (Foothill College), David Morrison (NASA Ames Research Center), Sidney C. Wolff (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) with many contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy).