9.2: The Solar Cycle

- Page ID

- 44099

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the sunspot cycle and, more generally, the solar cycle

- Explain how magnetism is the source of solar activity

Before the invention of the telescope, the Sun was thought to be an unchanging and perfect sphere. We now know that the Sun is in a perpetual state of change: its surface is a seething, bubbling cauldron of hot gas. Areas that are darker and cooler than the rest of the surface come and go. Vast plumes of gas erupt into the chromosphere and corona. Occasionally, there are even giant explosions on the Sun that send enormous streamers of charged particles and energy hurtling toward Earth. When they arrive, these can cause power outages and other serious effects on our planet.

Sunspots

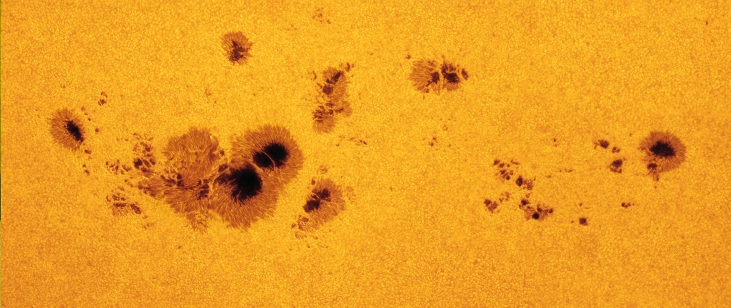

The first evidence that the Sun changes came from studies of sunspots, which are large, dark features seen on the surface of the Sun caused by increased magnetic activity. They look darker because the spots are typically at a temperature of about 3800 K, whereas the bright regions that surround them are at about 5800 K (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Occasionally, these spots are large enough to be visible to the unaided eye, and we have records going back over a thousand years from observers who noticed them when haze or mist reduced the Sun’s intensity. (We emphasize what your parents have surely told you: looking at the Sun for even a brief time can cause permanent eye damage. This is the one area of astronomy where we don’t encourage you to do your own observing without getting careful instructions or filters from your instructor.)

While we understand that sunspots look darker because they are cooler, they are nevertheless hotter than the surfaces of many stars. If they could be removed from the Sun, they would shine brightly. They appear dark only in contrast with the hotter, brighter photosphere around them.

Individual sunspots come and go, with lifetimes that range from a few hours to a few months. If a spot lasts and develops, it usually consists of two parts: an inner darker core, the umbra, and a surrounding less dark region, the penumbra. Many spots become much larger than Earth, and a few, like the largest one shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), have reached diameters over 140,000 kilometers. Frequently, spots occur in groups of 2 to 20 or more. The largest groups are very complex and may have over 100 spots. Like storms on Earth, sunspots are not fixed in position, but they drift slowly compared with the Sun’s rotation.

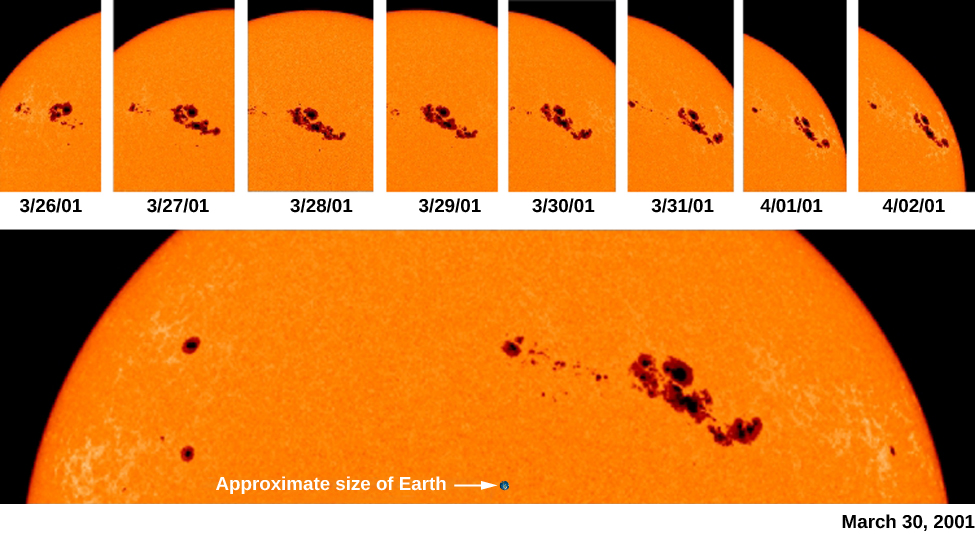

By recording the apparent motions of the sunspots as the turning Sun carried them across its disk (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), Galileo, in 1612, demonstrated that the Sun rotates on its axis with a rotation period of approximately 1 month. Our star turns in a west-to-east direction, like the orbital motions of the planets. The Sun, however, is a gas and does not have to rotate rigidly, the way a solid body like Earth does. Modern observations show that the speed of rotation of the Sun varies according to latitude, that is, it’s different as you go north or south of the Sun’s equator. The rotation period is about 25 days at the equator, 28 days at latitude 40°, and 36 days at latitude 80°. We call this behavior differential rotation.

The Sunspot Cycle

Between 1826 and 1850, Heinrich Schwabe, a German pharmacist and amateur astronomer, kept daily records of the number of sunspots. What he was really looking for was a planet inside the orbit of Mercury, which he hoped to find by observing its dark silhouette as it passed between the Sun and Earth. He failed to find the hoped-for planet, but his diligence paid off with an even-more important discovery: the sunspot cycle. He found that the number of sunspots varied systematically, in cycles about a decade long.

What Schwabe observed was that, although individual spots are short lived, the total number visible on the Sun at any one time was likely to be very much greater at certain times—the periods of sunspot maximum—than at other times—the periods of sunspot minimum. We now know that sunspot maxima occur at an average interval of 11 years, but the intervals between successive maxima have ranged from as short as 9 years to as long as 14 years. During sunspot maxima, more than 100 spots can often be seen at once. Even then, less than one-half of one percent of the Sun’s surface is covered by spots (Figure \(15.3.5\) in Section 15.3). During sunspot minima, sometimes no spots are visible. The Sun’s activity reached its most recent maximum in 2014.

Watch this brief video from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center that explains the sunspot cycle.

Magnetism and the Solar Cycle

Now that we have discussed the Sun’s activity cycle, you might be asking, “Why does the Sun change in such a regular way?” Astronomers now understand that it is the Sun’s changing magnetic field that drives solar activity.

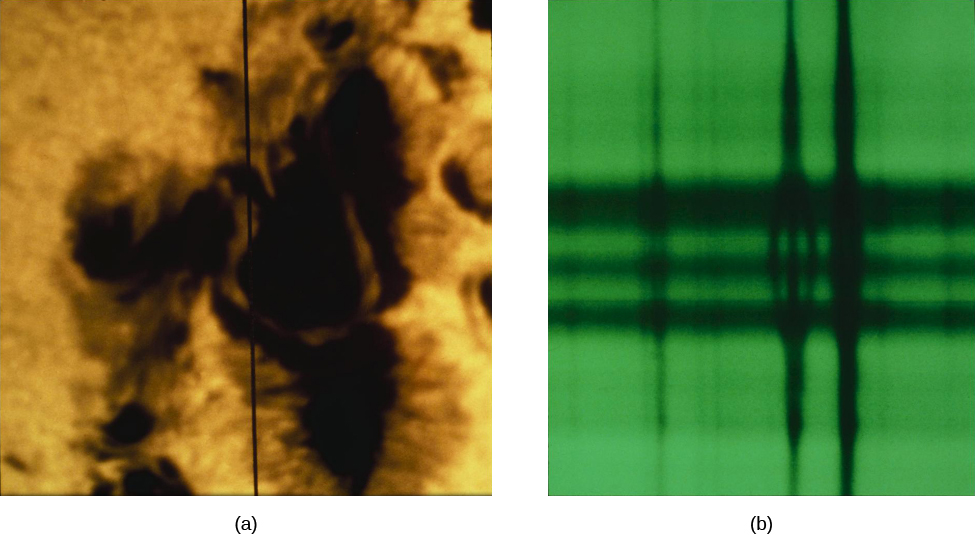

The solar magnetic field is measured using a property of atoms called the Zeeman effect. Recall from Radiation and Spectra that an atom has many energy levels and that spectral lines are formed when electrons shift from one level to another. If each energy level is precisely defined, then the difference between them is also quite precise. As an electron changes levels, the result is a sharp, narrow spectral line (either an absorption or emission line, depending on whether the electron’s energy increases or decreases in the transition).

In the presence of a strong magnetic field, however, each energy level is separated into several levels very close to one another. The separation of the levels is proportional to the strength of the field. As a result, spectral lines formed in the presence of a magnetic field are not single lines but a series of very closely spaced lines corresponding to the subdivisions of the atomic energy levels. This splitting of lines in the presence of a magnetic field is what we call the Zeeman effect (after the Dutch scientist who first discovered it in 1896).

Measurements of the Zeeman effect in the spectra of the light from sunspot regions show them to have strong magnetic fields (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Bear in mind that magnets always have a north pole and a south pole. Whenever sunspots are observed in pairs, or in groups containing two principal spots, one of the spots usually has the magnetic polarity of a north-seeking magnetic pole and the other has the opposite polarity. Moreover, during a given cycle, the leading spots of pairs (or leading principle spots of groups) in the Northern Hemisphere all tend to have the same polarity, whereas those in the Southern Hemisphere all tend to have the opposite polarity.

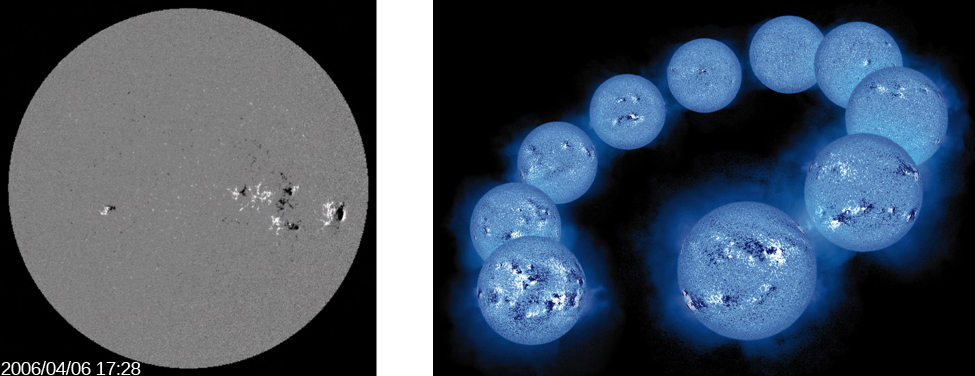

During the next sunspot cycle, however, the polarity of the leading spots is reversed in each hemisphere. For example, if during one cycle, the leading spots in the Northern Hemisphere all had the polarity of a north-seeking pole, then the leading spots in the Southern Hemisphere would have the polarity of a south-seeking pole. During the next cycle, the leading spots in the Northern Hemisphere would have south-seeking polarity, whereas those in the Southern Hemisphere would have north-seeking polarity. Therefore, strictly speaking, the sunspot cycle does not repeat itself in regard to magnetic polarity until two 11-year cycles have passed. A visual representation of the Sun’s magnetic fields, called a magnetogram, can be used to see the relationship between sunspots and the Sun’s magnetic field (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Why is the Sun such a strong and complicated magnet? Astronomers have found that it is the Sun’s dynamo that generates the magnetic field. A dynamo is a machine that converts kinetic energy (i.e., the energy of motion) into electricity. On Earth, dynamos are found in power plants where, for example, the energy from wind or flowing water is used to cause turbines to rotate. In the Sun, the source of kinetic energy is the churning of turbulent layers of ionized gas within the Sun’s interior that we mentioned earlier. These generate electric currents—moving electrons—which in turn generate magnetic fields.

Most solar researchers agree that the solar dynamo is located in the convection zone or in the interface layer between the convection zone and the radiative zone below it. As the magnetic fields from the Sun’s dynamo interact, they break, reconnect, and rise through the Sun’s surface.

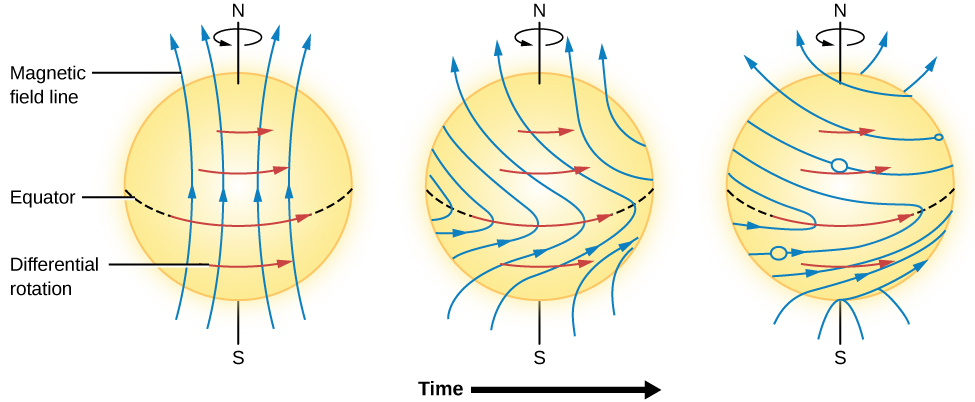

We should say that, although we have good observations that show us how the Sun changes during each solar cycle, it is still very difficult to build physical models of something as complicated as the Sun that can account satisfactorily for why it changes. Researchers have not yet developed a generally accepted model that describes in detail the physical processes that control the solar cycle. Calculations do show that differential rotation (the idea that the Sun rotates at different rates at different latitudes) and convection just below the solar surface can twist and distort the magnetic fields. This causes them to grow and then decay, regenerating with opposite polarity approximately every 11 years. The calculations also show that as the fields grow stronger near solar maximum, they flow from the interior of the Sun toward its surface in the form of loops. When a large loop emerges from the solar surface, it creates regions of sunspot activity (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

This idea of magnetic loops offers a natural explanation of why the leading and trailing sunspots in an active region have opposite polarity. The leading sunspot coincides with one end of the loop and the trailing spot with the other end. Magnetic fields also hold the key to explaining why sunspots are cooler and darker than the regions without strong magnetic fields. The forces produced by the magnetic field resist the motions of the bubbling columns of rising hot gases. Since these columns carry most of the heat from inside the Sun to the surface by means of convection, and strong magnetic fields inhibit this convection, the surface of the Sun is allowed to cool. As a result, these regions are seen as darker, cooler sunspots.

Beyond this general picture, researchers are still trying to determine why the magnetic fields are as large as they are, why the polarity of the field in each hemisphere flips from one cycle to the next, why the length of the solar cycle can vary from one cycle to the next, and why events like the Maunder Minimum occur.

In this video solar scientist Holly Gilbert discusses the Sun’s magnetic field.

Key Concepts and Summary

Sunspots are dark regions where the temperature is up to 2000 K cooler than the surrounding photosphere. Their motion across the Sun’s disk allows us to calculate how fast the Sun turns on its axis. The Sun rotates more rapidly at its equator, where the rotation period is about 25 days, than near the poles, where the period is slightly longer than 36 days. The number of visible sunspots varies according to a sunspot cycle that averages 11 years in length. Spots frequently occur in pairs. During a given 11-year cycle, all leading spots in the Northern Hemisphere have the same magnetic polarity, whereas all leading sports in the Southern Hemisphere have the opposite polarity. In the subsequent 11-year cycle, the polarity reverses. For this reason, the magnetic activity cycle of the Sun is understood to last for 22 years. This activity cycle is connected with the behavior of the Sun’s magnetic field, but the exact mechanism is not yet understood.

Glossary

- differential rotation

- the phenomenon that occurs when different parts of a rotating object rotate at different rates at different latitudes

- Maunder Minimum

- a period during the eighteenth century when the number of sunspots seen throughout the solar cycle was unusually low

- sunspot

- large, dark features seen on the surface of the Sun caused by increased magnetic activity

- sunspot cycle

- the semiregular 11-year period with which the frequency of sunspots fluctuates

Contributors and Attributions

Andrew Fraknoi (Foothill College), David Morrison (NASA Ames Research Center), Sidney C. Wolff (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) with many contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy).