10.9: Fundamental Units of Distance

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the importance of defining a standard distance unit

- Explain how the meter was originally defined and how it has changed over time

- Discuss how radar is used to measure distances to the other members of the solar system

The first measures of distances were based on human dimensions—the inch as the distance between knuckles on the finger, or the yard as the span from the extended index finger to the nose of the British king. Later, the requirements of commerce led to some standardization of such units, but each nation tended to set up its own definitions. It was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that any real efforts were made to establish a uniform, international set of standards.

The Metric System

One of the enduring legacies of the era of the French emperor Napoleon is the establishment of the metric system of units, officially adopted in France in 1799 and now used in most countries around the world. The fundamental metric unit of length is the meter, originally defined as one ten-millionth of the distance along Earth’s surface from the equator to the pole. French astronomers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were pioneers in determining the dimensions of Earth, so it was logical to use their information as the foundation of the new system.

Practical problems exist with a definition expressed in terms of the size of Earth, since anyone wishing to determine the distance from one place to another can hardly be expected to go out and re-measure the planet. Therefore, an intermediate standard meter consisting of a bar of platinum-iridium metal was set up in Paris. In 1889, by international agreement, this bar was defined to be exactly one meter in length, and precise copies of the original meter bar were made to serve as standards for other nations.

Other units of length are derived from the meter. Thus, 1 kilometer (km) equals 1000 meters, 1 centimeter (cm) equals 1/100 meter, and so on. Even the old British and American units, such as the inch and the mile, are now defined in terms of the metric system.

Modern Redefinitions of the Meter

In 1960, the official definition of the meter was changed again. As a result of improved technology for generating spectral lines of precisely known wavelengths (see the chapter on Radiation and Spectra), the meter was redefined to equal 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of a particular atomic transition in the element krypton-86. The advantage of this redefinition is that anyone with a suitably equipped laboratory can reproduce a standard meter, without reference to any particular metal bar.

In 1983, the meter was defined once more, this time in terms of the velocity of light. Light in a vacuum can travel a distance of one meter in 1/299,792,458.6 second. Today, therefore, light travel time provides our basic unit of length. Put another way, a distance of one light-second (the amount of space light covers in one second) is defined to be 299,792,458.6 meters. That’s almost 300 million meters that light covers in just one second; light really is very fast! We could just as well use the light-second as the fundamental unit of length, but for practical reasons (and to respect tradition), we have defined the meter as a small fraction of the light-second.

Distance within the Solar System

The work of Copernicus and Kepler established the relative distances of the planets—that is, how far from the Sun one planet is compared to another (see Observing the Sky: The Birth of Astronomy and Orbits and Gravity). But their work could not establish the absolute distances (in light-seconds or meters or other standard units of length). This is like knowing the height of all the students in your class only as compared to the height of your astronomy instructor, but not in inches or centimeters. Somebody’s height has to be measured directly.

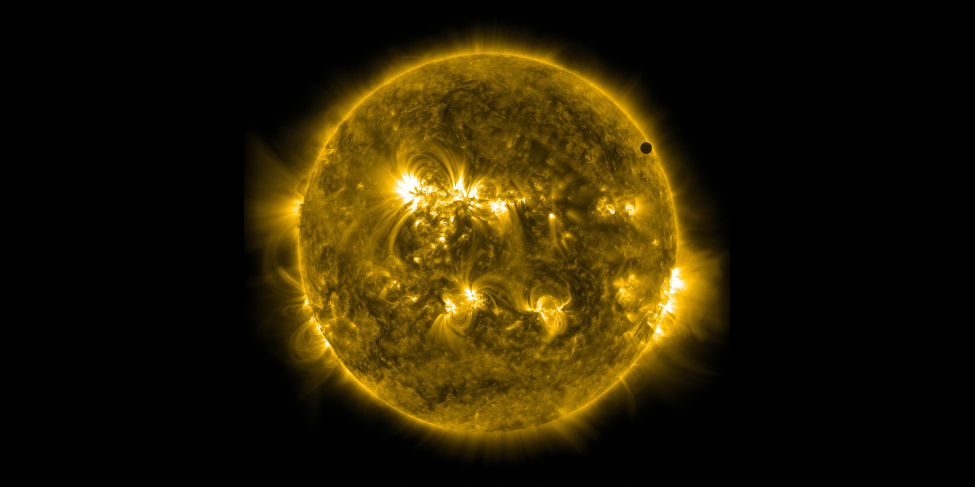

Similarly, to establish absolute distances, astronomers had to measure one distance in the solar system directly. Generally, the closer to us the object is, the easier such a measurement would be. Estimates of the distance to Venus were made as Venus crossed the face of the Sun in 1761 and 1769, and an international campaign was organized to estimate the distance to the asteroid Eros in the early 1930s, when its orbit brought it close to Earth. More recently, Venus crossed (or transited) the surface of the Sun in 2004 and 2012, and allowed us to make a modern distance estimate, although, as we will see below, by then it wasn’t needed (Figure 10.9.1).

The key to our modern determination of solar system dimensions is radar, a type of radio wave that can bounce off solid objects (Figure 10.9.2). As discussed in several earlier chapters, by timing how long a radar beam (traveling at the speed of light) takes to reach another world and return, we can measure the distance involved very accurately. In 1961, radar signals were bounced off Venus for the first time, providing a direct measurement of the distance from Earth to Venus in terms of light-seconds (from the roundtrip travel time of the radar signal).

Subsequently, radar has been used to determine the distances to Mercury, Mars, the satellites of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, and several asteroids. Note, by the way, that it is not possible to use radar to measure the distance to the Sun directly because the Sun does not reflect radar very efficiently. But we can measure the distance to many other solar system objects and use Kepler’s laws to give us the distance to the Sun.

From the various (related) solar system distances, astronomers selected the average distance from Earth to the Sun as our standard “measuring stick” within the solar system. When Earth and the Sun are closest, they are about 147.1 million kilometers apart; when Earth and the Sun are farthest, they are about 152.1 million kilometers apart. The average of these two distances is called the astronomical unit (AU). We then express all the other distances in the solar system in terms of the AU. Years of painstaking analyses of radar measurements have led to a determination of the length of the AU to a precision of about one part in a billion. The length of 1 AU can be expressed in light travel time as 499.004854 light-seconds, or about 8.3 light-minutes. If we use the definition of the meter given previously, this is equivalent to 1 AU = 149,597,870,700 meters.

These distances are, of course, given here to a much higher level of precision than is normally needed. In this text, we are usually content to express numbers to a couple of significant places and leave it at that. For our purposes, it will be sufficient to round off these numbers:

speed of light: c=3×108 m/s =3×105 km/s length of light-second: ls=3×108 m =3×105 km astronomical unit: AU=1.50×1011 m =1.50×108 km =500 light-seconds

We now know the absolute distance scale within our own solar system with fantastic accuracy. This is the first link in the chain of cosmic distances.

The distances between the celestial bodies in our solar system are sometimes difficult to grasp or put into perspective. This interactive website provides a “map” that shows the distances by using a scale at the bottom of the screen and allows you to scroll (using your arrow keys) through screens of “empty space” to get to the next planet—all while your current distance from the Sun is visible on the scale.

Key Concepts and Summary

Early measurements of length were based on human dimensions, but today, we use worldwide standards that specify lengths in units such as the meter. Distances within the solar system are now determined by timing how long it takes radar signals to travel from Earth to the surface of a planet or other body and then return.

Contributors and Attributions

Andrew Fraknoi (Foothill College), David Morrison (NASA Ames Research Center), Sidney C. Wolff (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) with many contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy).