13.15: Observations of Distant Galaxies

- Page ID

- 44174

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how astronomers use light to learn about distant galaxies long ago

- Discuss the evidence showing that the first stars formed when the universe was less than 10% of its current age

- Describe the major differences observed between galaxies seen in the distant, early universe and galaxies seen in the nearby universe today

Let’s begin by exploring some techniques astronomers use to study how galaxies are born and change over cosmic time. Suppose you wanted to understand how adult humans got to be the way they are. If you were very dedicated and patient, you could actually observe a sample of babies from birth, following them through childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood, and making basic measurements such as their heights, weights, and the proportional sizes of different parts of their bodies to understand how they change over time.

Unfortunately, we have no such possibility for understanding how galaxies grow and change over time: in a human lifetime—or even over the entire history of human civilization—individual galaxies change hardly at all. We need other tools than just patiently observing single galaxies in order to study and understand those long, slow changes.

We do, however, have one remarkable asset in studying galactic evolution. As we have seen, the universe itself is a kind of time machine that permits us to observe remote galaxies as they were long ago. For the closest galaxies, like the Andromeda galaxy, the time the light takes to reach us is on the order of a few hundred thousand to a few million years. Typically not much changes over times that short—individual stars in the galaxy may be born or die, but the overall structure and appearance of the galaxy will remain the same. But we have observed galaxies so far away that we are seeing them as they were when the light left them more than 10 billion years ago.

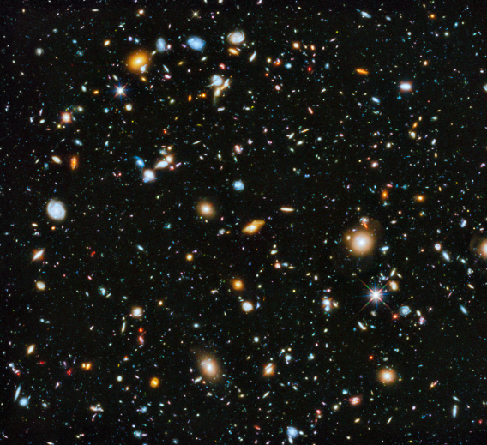

By observing more distant objects, we look further back toward a time when both galaxies and the universe were young (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). This is a bit like getting letters in the mail from several distant friends: the farther the friend was when she mailed the letter to you, the longer the letter must have been in transit, and so the older the news is when it arrives in your mailbox; you are learning something about her life at an earlier time than when you read the letter.

If we can’t directly detect the changes over time in individual galaxies because they happen too slowly, how then can we ever understand those changes and the origins of galaxies? The solution is to observe many galaxies at many different cosmic distances and, therefore, look-back times (how far back in time we are seeing the galaxy). If we can study a thousand very distant “baby” galaxies when the universe was 1 billion years old, and another thousand slightly closer “toddler” galaxies when it was 2 billion years old, and so on until the present 13.8-billion-year-old universe of mature “adult” galaxies near us today, then maybe we can piece together a coherent picture of how the whole ensemble of galaxies evolves over time. This allows us to reconstruct the “life story” of galaxies since the universe began, even though we can’t follow a single galaxy from infancy to old age.

Fortunately, there is no shortage of galaxies to study. Hold up your pinky at arm’s length: the part of the sky blocked by your fingernail contains about one million galaxies, layered farther and farther back in space and time. In fact, the sky is filled with galaxies, all of them, except for Andromeda and the Magellanic Clouds, too faint to see with the naked eye—more than 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe, each one with about 100 billion stars.

This cosmic time machine, then, lets us peer into the past to answer fundamental questions about where galaxies come from and how they got to be the way they are today. Astronomers call those galactic changes over cosmic time evolution, a word that recalls the work of Darwin and others on the development of life on Earth. But note that galaxy evolution refers to the changes in individual galaxies over time, while the kind of evolution biologists study is changes in successive generations of living organisms over time.

Spectra, Colors, and Shapes

Astronomy is one of the few sciences in which all measurements must be made at a distance. Geologists can take samples of the objects they are studying; chemists can conduct experiments in their laboratories to determine what a substance is made of; archeologists can use carbon dating to determine how old something is. But astronomers can’t pick up and play with a star or galaxy. As we have seen throughout this book, if they want to know what galaxies are made of and how they have changed over the lifetime of the universe, they must decode the messages carried by the small number of photons that reach Earth.

Fortunately (as you have learned) electromagnetic radiation is a rich source of information. The distance to a galaxy is derived from its redshift (how much the lines in its spectrum are shifted to the red because of the expansion of the universe). The conversion of redshift to a distance depends on certain properties of the universe, including the value of the Hubble constant and how much mass it contains. We will describe the currently accepted model of the universe in The Big Bang. For the purposes of this chapter, it is enough to know that the current best estimate for the age of the universe is 13.8 billion years. In that case, if we see an object that emitted its light 6 billion light-years ago, we are seeing it as it was when the universe was almost 8 billion years old. If we see something that emitted its light 13 billion years ago, we are seeing it as it was when the universe was less than a billion years old. So astronomers measure a galaxy’s redshift from its spectrum, use the Hubble constant plus a model of the universe to turn the redshift into a distance, and use the distance and the constant speed of light to infer how far back in time they are seeing the galaxy—the look-back time.

In addition to distance and look-back time, studies of the Doppler shifts of a galaxy’s spectral lines can tell us how fast the galaxy is rotating and hence how massive it is (as explained in Galaxies). Detailed analysis of such lines can also indicate the types of stars that inhabit a galaxy and whether it contains large amounts of interstellar matter.

Unfortunately, many galaxies are so faint that collecting enough light to produce a detailed spectrum is currently impossible. Astronomers thus have to use a much rougher guide to estimate what kinds of stars inhabit the faintest galaxies—their overall colors. Look again at Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and notice that some of the galaxies are very blue and others are reddish-orange. Now remember that hot, luminous blue stars are very massive and have lifetimes of only a few million years. If we see a galaxy where blue colors dominate, we know that it must have many hot, luminous blue stars, and that star formation must have taken place in the few million years before the light left the galaxy. In a yellow or red galaxy, on the other hand, the young, luminous blue stars that surely were made in the galaxy’s early bursts of star formation must have died already; it must contain mostly old yellow and red stars that last a long time in their main-sequence stages and thus typically formed billions of years before the light that we now see was emitted.

Another important clue to the nature of a galaxy is its shape. Spiral galaxies can be distinguished from elliptical galaxies by shape. Observations show that spiral galaxies contain young stars and large amounts of interstellar matter, while elliptical galaxies have mostly old stars and very little or no star formation. Elliptical galaxies turned most of their interstellar matter into stars many billions of years ago, while star formation has continued until the present day in spiral galaxies.

If we can count the number of galaxies of each type during each epoch of the universe, it will help us understand how the pace of star formation changes with time. As we will see later in this chapter, galaxies in the distant universe—that is, young galaxies—look very different from the older galaxies that we see nearby in the present-day universe.

The First Generation of Stars

In addition to looking at the most distant galaxies we can find, astronomers look at the oldest stars (what we might call the fossil record) of our own Galaxy to probe what happened in the early universe. Since stars are the source of nearly all the light emitted by galaxies, we can learn a lot about the evolution of galaxies by studying the stars within them. What we find is that nearly all galaxies contain at least some very old stars. For example, our own Galaxy contains globular clusters with stars that are at least 13 billion years old, and some may be even older than that. Therefore, if we count the age of the Milky Way as the age of its oldest constituents, the Milky Way must have been born at least 13 billion years ago.

As we will discuss in The Big Bang, astronomers have discovered that the universe is expanding, and have traced the expansion backward in time. In this way, they have discovered that the universe itself is only about 13.8 billion years old. Thus, it appears that at least some of the globular-cluster stars in the Milky Way must have formed less than a billion years after the expansion began.

Several other observations also establish that star formation in the cosmos began very early. Astronomers have used spectra to determine the composition of some elliptical galaxies that are so far away that the light we see left them when the universe was only half as old as it is now. Yet these ellipticals contain old red stars, which must have formed billions of years earlier still.

When we make computer models of how such galaxies evolve with time, they tell us that star formation in elliptical galaxies began less than a billion years or so after the universe started its expansion, and new stars continued to form for a few billion years. But then star formation apparently stopped. When we compare distant elliptical galaxies with ones nearby, we find that ellipticals have not changed very much since the universe reached about half its current age. We’ll return to this idea later in the chapter.

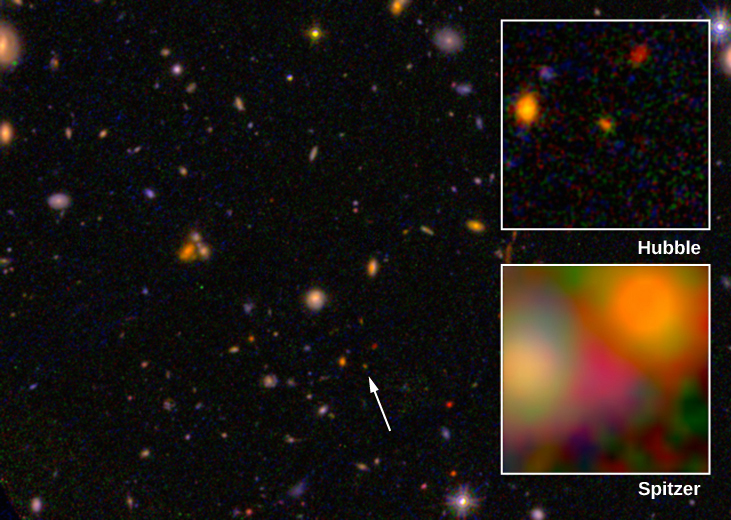

Observations of the most luminous galaxies take us even further back in time. Recently, as we have already noted, astronomers have discovered a few galaxies that are so far away that the light we see now left them less than a billion years or so after the beginning (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Yet the spectra of some of these galaxies already contain lines of heavy elements, including carbon, silicon, aluminum, and sulfur. These elements were not present when the universe began but had to be manufactured in the interiors of stars. This means that when the light from these galaxies was emitted, an entire generation of stars had already been born, lived out their lives, and died—spewing out the new elements made in their interiors through supernova explosions—even before the universe was a billion years old. And it wasn’t just a few stars in each galaxy that got started this way. Enough had to live and die to affect the overall composition of the galaxy, in a way that we can still measure in the spectrum from far away.

Observations of quasars (galaxies whose centers contain a supermassive black hole) support this conclusion. We can measure the abundances of heavy elements in the gas near quasar black holes (explained in Active Galaxies, Quasars, and Supermassive Black Holes). The composition of this gas in quasars that emitted their light 12.5 billion light-years ago is very similar to that of the Sun. This means that a large portion of the gas surrounding the black holes must have already been cycled through stars during the first 1.3 billion years after the expansion of the universe began. If we allow time for this cycling, then their first stars must have formed when the universe was only a few hundred million years old.

A Changing Universe of Galaxies

Back in the middle decades of the twentieth century, the observation that all galaxies contain some old stars led astronomers to the hypothesis that galaxies were born fully formed near the time when the universe began its expansion. This hypothesis was similar to suggesting that human beings were born as adults and did not have to pass through the various stages of development from infancy through the teens. If this hypothesis were correct, the most distant galaxies should have shapes and sizes very much like the galaxies we see nearby. According to this old view, galaxies, after they formed, should then change only slowly, as successive generations of stars within them formed, evolved, and died. As the interstellar matter was slowly used up and fewer new stars formed, the galaxies would gradually become dominated by fainter, older stars and look dimmer and dimmer.

Thanks to the new generation of large ground- and space-based telescopes, we now know that this picture of galaxies evolving peacefully and in isolation from one another is completely wrong. As we will see later in this chapter, galaxies in the distant universe do not look like the Milky Way and nearby galaxies such as Andromeda, and the story of their development is more complex and involves far more interaction with their neighbors.

Why were astronomers so wrong? Up until the early 1990s, the most distant normal galaxy that had been observed emitted its light 8 billion years ago. Since that time, many galaxies—and particularly the giant ellipticals, which are the most luminous and therefore the easiest to see at large distances—did evolve peacefully and slowly. But the Hubble, Spitzer, Herschel, Keck, and other powerful new telescopes that have come on line since the 1990s make it possible to pierce the 8-billion-light-year barrier. We now have detailed views of many thousands of galaxies that emitted their light much earlier (some more than 13 billion years ago—see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Much of the recent work on the evolution of galaxies has progressed by studying a few specific small regions of the sky where the Hubble, Spitzer, and ground-based telescopes have taken extremely long exposure images. This allowed astronomers to detect very faint, very distant, and therefore very young galaxies (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Our deep space telescope images show some galaxies that are 100 times fainter than the faintest objects that can be observed spectroscopically with today’s giant ground-based telescopes. This turns out to mean that we can obtain the spectra needed to determine redshifts for only the very brightest five percent of the galaxies in these images.

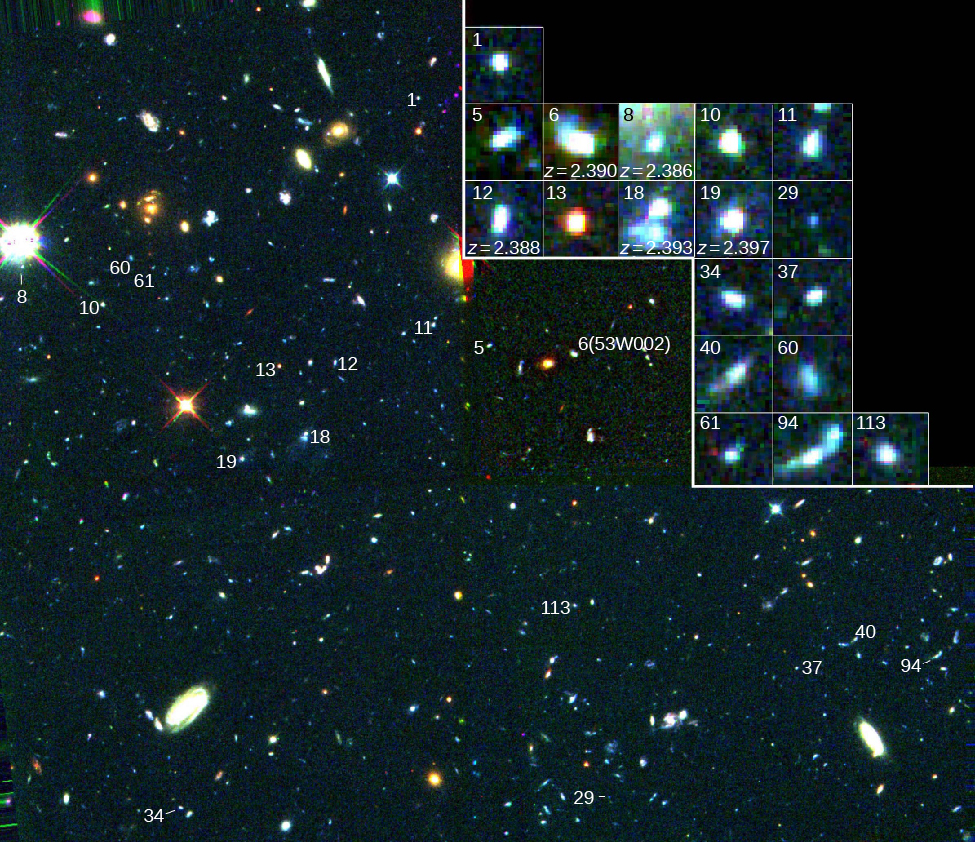

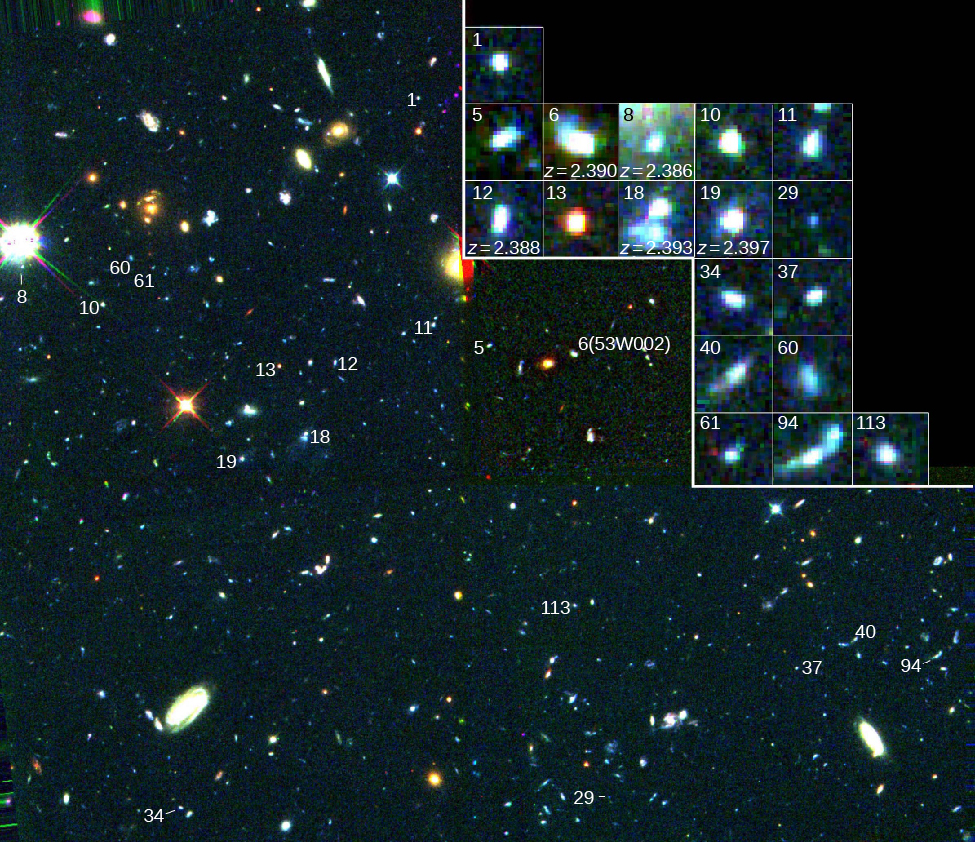

Although we do not have spectra for most of the faint galaxies, the Hubble Space Telescope is especially well suited to studying their shapes because the images taken in space are not blurred by Earth’s atmosphere. To the surprise of astronomers, the distant galaxies did not fit Hubble’s classification scheme at all. Remember that Hubble found that nearly all nearby galaxies could be classified into a few categories, depending on whether they were ellipticals or spirals. The distant galaxies observed by the Hubble Space Telescope look very different from present-day galaxies, without identifiable spiral arms, disks, and bulges (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). They also tend to be much clumpier than most galaxies today. In other words, it’s becoming clear that the shapes of galaxies have changed significantly over time. In fact, we now know that the Hubble scheme works well for only the last half of the age of the universe. Before then, galaxies were much more chaotic.

It’s not just the shapes that are different. Nearly all the galaxies at distances greater than 11 billion light-years—that is, galaxies that we are seeing when they were less than 3 billion years old—are extremely blue, indicating that they contain a lot of young stars and that star formation in them is occurring at a higher rate than in nearby galaxies. Observations also show that very distant galaxies are systematically smaller on average than nearby galaxies. Relatively few galaxies present before the universe was about 8 billion years old have masses greater than \(10^{11}\) \(M_{\text{Sun}}\). That’s 1/20 the mass of the Milky Way if we include its dark matter halo. Eleven billion years ago, there were only a few galaxies with masses greater than \(10^{10}\) \(M_{\text{Sun}}\). What we see instead seem to be small pieces or fragments of galactic material (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). When we look at galaxies that emitted their light 11 to 12 billion years ago, we now believe we are seeing the seeds of elliptical galaxies and of the central bulges of spirals. Over time, these smaller galaxies collided and merged to build up today’s large galaxies.

Bear in mind that stars that formed more than 11 billion years ago will be very old stars today. Indeed when we look nearby (at galaxies we see closer to our time), we find mostly old stars in the nuclear bulges of nearby spirals and in elliptical galaxies.

What such observations are showing us is that galaxies have grown in size as the universe has aged. Not only were galaxies smaller several billion years ago, but there were more of them; gas-rich galaxies, particularly the less luminous ones, were much more numerous then than they are today.

Those are some of the basic observations we can make of individual galaxies (and their evolution) looking back in cosmic time. Now we want to turn to the larger context. If stars are grouped into galaxies, are the galaxies also grouped in some way? In the third section of this chapter, we’ll explore the largest structures known in the universe.

Summary

When we look at distant galaxies, we are looking back in time. We have now seen galaxies as they were when the universe was about 500 million years old—only about five percent as old as it is now. The universe now is 13.8 billion years old. The color of a galaxy is an indicator of the age of the stars that populate it. Blue galaxies must contain a lot of hot, massive, young stars. Galaxies that contain only old stars tend to be yellowish red. The first generation of stars formed when the universe was only a few hundred million years old. Galaxies observed when the universe was only a few billion years old tend to be smaller than today’s galaxies, to have more irregular shapes, and to have more rapid star formation than the galaxies we see nearby in today’s universe. This shows that the smaller galaxy fragments assembled themselves into the larger galaxies we see today.

Glossary

- evolution (of galaxies)

- changes in individual galaxies over cosmic time, inferred by observing snapshots of many different galaxies at different times in their lives

Contributors and Attributions

Andrew Fraknoi (Foothill College), David Morrison (NASA Ames Research Center), Sidney C. Wolff (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) with many contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy).