learning objectives

- Formulate major changes in the understanding of time, space, mass, and energy that were introduced by the theory of Special Relativity

The theory of Special Relativity and its implications spurred a paradigm shift in our understanding of the nature of the universe, the fundamental fabric of which being space and time. Before 1905, scientists considered space and time as completely independent objects. Time could not affect space and space could not affect time. After 1905, however, the Special Theory of Relativity destroyed this old, but intuitive, view. Specifically, Special Relativity showed us that space and time are not independent of one another but can be mixed into each other and therefore must be considered as the same object, which we shall denote as space-time. The consequences of space/time mixing are:

- time dilation

- and length contraction.

Other important consequences which will be discussed in another section are

- Relativity of Simultaneity (for certain events, the sequence in which they occur is dependent on the observer)

- Nothing can move faster than the speed of light (we shall denote the value of the speed of light as cc)

Why is there a mixing between space and time? In order to examine this we must know the founding principles of relativity. They are:

- The Principle of Relativity: The laws of physics for observers which are not accelerating relative to one another should be the same.

- The Principle of Invariant Light Speed: All observers, moving at constant speed, measure the same speed of light regardless of how fast they are moving.

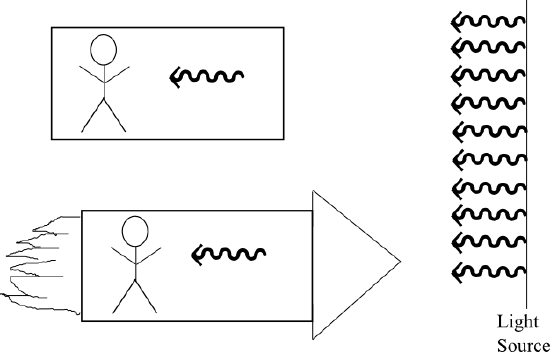

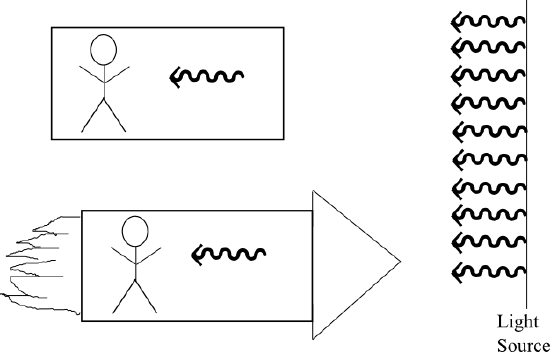

If one accepts the second principle as fact then it immediately follows that space and time are not independent. Why? Let us look at the experiment in in which there is a light source, a fixed observer, and a rocket ship moving toward the light source. The two observers are related by a coordinate , or space-time, transformation. The second principle then tells us that no matter how fast the rocket is moving, both observers must measure the same light speed emanating from the source. The only way this can happen is if the clock of the rocket observer is ticking at a different rate than the stationary observer. How much different? This can be expressed in the time dilation equation:

Measuring Light: A stationary observer will measure the same speed of light as an observer who is moving in a rocket ship even if that rocket is moving close to light speed.

\[\mathrm { t } _ { \mathrm { s } } = \dfrac { \mathrm { t } _ { \mathrm { m } } } { \sqrt { 1 - \left( \dfrac { \mathrm{v} ^ { 2 } } { \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } } \right) } }\]

Where tsts is the time elapsed for the stationary observer, tmtm is the time elapsed for the moving observer, and vv is the velocity of the rocket as measured from the stationary frame. One can then see that as \(\mathrm { V } \rightarrow \mathrm { C }\) then the time elapsed in the stationary frame goes to infinity. To place some numbers, let \(\mathrm { v } = 0.99986 \mathrm { c }\), and \(\mathrm { t } _ { \mathrm { m } } = \mathrm { 1 \; sec } \) . The time elapsed in the stationary frame is then one hour. Thus for every second lived in the rocket, the stationary man lives one hour!

One of the more radical results of time dilation is the so-called “twin paradox. ” The twin paradox is a thought experiment in special relativity that involves identical twins. One of the twins goes on a journey into space in a rocket that has a velocity near the speed of light. Upon returning home the twin finds that the twin that remained on Earth has aged more. This consequence altered the perception that aging is necessarily constant.

The square root factor in the time dilation equation is very important and we denote it as:

This factor shows up frequently in special relativity. For example the length contraction formula is:

\[\mathrm { L } = \mathrm { L } _ { 0 } \sqrt { 1 - \left( \dfrac { \mathrm{v} } { \mathrm{c} } \right) } = \dfrac { \mathrm { L } _ { 0 } } { \gamma }\]

where \(\mathrm{L_0}\) is the rest length, the length of an object measured in the co-moving frame of the object, and \(\mathrm{L}\) is the length of the object as measured by the observer who sees the object moving at speed \(\mathrm{v}\). In our rocket example, the stationary observer measures the length of the rocket as being less than what someone who was moving with the rocket would measure. This altered the perception that the length of an object would appear the same regardless of the reference frame of the observer.

Another radical finding that was made possible by the discovery of special relativity is the equivalence of energy and mass. Combined with other laws of physics, the postulates of special relativity predict that mass and energy are related by: \(\mathrm{E=mc^2}\), where c is the speed of light in vacuum. This altered the perception that mass and energy are completely different things and paved the way for nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

As a final note it is important to note how big the speed of light is compared to every day life. The speed of light is:

\[\mathrm { c } = 3 \times 10 ^ { 8 } \mathrm { m } / \mathrm { s }\]

Thus in every day life \(\mathrm{γ≈1}\) and we do not experience significant time dilation or length contraction. If we did, life would be very different.

Four-Dimensional Space-Time

We live in four-dimensional space-time, in which the ordering of certain events can depend on the observer.

learning objectives

- Formulate major results of special relativity

Working in Four Dimensions

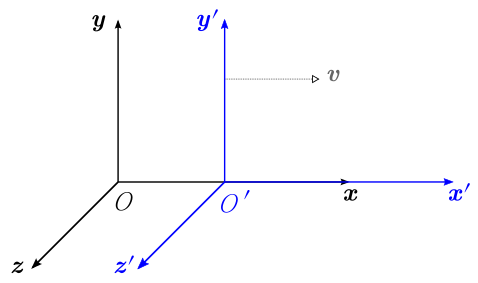

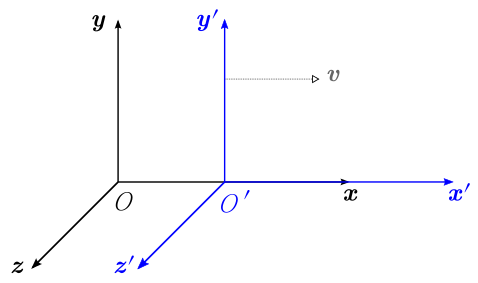

Let us examine two observers who are moving relative to one another at a constant velocity. We shall denote them as observer A and observer A’. Observer A sets up a space-time coordinate system (t, x, y, z); similarly, A’ sets up his own space-time coordinate system (t’, x’, y’, z’). (See for an example. ) Therefore both observers live in a four-dimensional world with three space dimensions and one time dimension.

Two Coordinate Systems: Two coordinate systems in which the primed frame moves with velocity v with respect to the unprimed frame

You should not find it odd to work with four dimensions; any time you have to meet your friend somewhere you have to tell him four variables: where (three spatial coordinates) and when (one time coordinate). In other words, we have always lived in four dimensions, but so far you have probably thought of space and time as completely separate.

The Movement of Light in Four Dimensions

Back to our example: let us assume that at some point in space-time there is a beam of light that emerges. Both observers measure how far the beam has traveled at each point in time and how long it took to travel to travel that distance. That is to say, observer A measures:

\(\mathrm{( \Delta t , \Delta x , \Delta y , \Delta z )}\)

where, for example, \(\mathrm{\Delta t = t - t _ { 0 }}\); t is the time at which the measurement took place; and t0 is the time at which the light was turned on.

Similarly, observer A’ measures:

\(\left( \Delta t ^ { \prime } , \Delta x ^ { \prime } , \Delta y ^ { \prime } , \Delta z ^ { \prime } \right)\)

where we set up the system such that both observers agree on \(\left( \mathrm { t } _ { 0 } , \mathrm { x } _ { 0 } , \mathrm { y } _ { 0 } , \mathrm { z } _ { 0 } \right)\). Due to the invariance of the speed of light both observers will agree on:

\[\dfrac { \Delta \mathrm { X } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { Y } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { Z } ^ { 2 } } { \Delta \mathrm { T } ^ { 2 } } = \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } \rightarrow 0 = - \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } \Delta \mathrm { T } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { X } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { Y } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { Z } ^ { 2 }\]

where \(\mathrm{(T,X,Y,Z)}\)refers to the coordinates in either frame. Therefore there is a specific rule that all light paths must follow. For general events we can define the quantity:

\[\mathrm{s} ^ { 2 } = - \mathrm{c} ^ { 2 } \Delta t ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm{x} ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm{y} ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm{z} ^ { 2 }\]

This is known as the line element and is the same for all observers. (Using the principles of relativity, you can prove this for general separations, not just light rays). The set of all coordinate transformations that leave the above quantity invariant are known as Lorentz Transformations. It follows that the coordinate systems of all physical observers are related to each other by Lorentz Transformations. (The set of all Lorentz transformations form what mathematicians call a group, and the study of group theory has revolutionized physics). For the coordinate transformation in, the transformations are:

\[\left. \begin{array} { l } { \mathrm { t } ^ { \prime } = \gamma \left( \mathrm { t } - \mathrm { vx } / \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } \right) } \\ { \mathrm { x } ^ { \prime } = \gamma ( \mathrm { x } - \mathrm { vt } ) } \\ { \mathrm { y } ^ { \prime } = \mathrm { y } } \\ { \mathrm { z } ^ { \prime } = \mathrm { z } } \end{array} \right.\]

where

\[\gamma = \dfrac { 1 } { \sqrt { 1 - ( \mathrm{ v } / \mathrm { c } ) ^ { 2 } } }\]

We define the separation between space-time points as follows:

\[\mathrm { s } ^ { 2 } > 0 : \text { space-like }\]

\[\mathrm { s } ^ { 2 } < 0 : \text { time-like }\]

\[\mathrm { s } ^ { 2 } = 0 : \text { null }\]

We separate these events because they are very different. For example, for a space-like separation you can always find a coordinate transformation that reverses the time-ordering of the events (try to prove this for the example in ). This phenomenon is known as the relativity of simultaneity and may be counterintuitive.

Space-Like Space-Time Separations

Let us examine two car crashes, one in New York and one in London, such that they occur in the same time in one frame. In this situation, the space-time separation between the two events is space-like. The question of whether the events are simultaneous is relative: in some reference frames the two accidents may happen at the same time; in other frames (in a different state of motion relative to the events) the crash in London may occur first; and in still other frames the New York crash may occur first. (In practice, this does not affect us because the frames that switch the order of the events must move at unreachably high speeds. )

Time-Like and Null Space-Time Separations

Events that are time-like or null do not share this property, and therefore there is a causal ordering between time-like events. In other words, if two events are time-like separated, then they can effect each other. The reason is that if two space-time points are time-like or null separated, one can always send a light signal from one point to another.

Special Relativity

Finally, let’s discuss an important result of special relativity — that the energy EE of an object moving with speed vv is:

\[\mathrm { E } = \frac { \mathrm { m } _ { 0 } \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } } { \sqrt { 1 - ( \mathrm { v } / \mathrm { c } ) ^ { 2 } } } = \mathrm { mc } ^ { 2 }\]

where m0m0 is the mass of the object at rest and m=γm0m=γm0 is the mass when the object is moving. The above formula immediately shows why it is impossible to travel faster than the speed of light. As \(\mathrm { v } \rightarrow \mathrm { c } , \mathrm { m } \rightarrow \infty \) , and it takes an infinite amount of energy to accelerate the object further.

The Relativistic Universe

Gravity is a geometrical effect in which a metric matrix plays a special role, and the motion of objects are altered by curved space.

learning objectives

- Identify factors that affect motion near massive objects

Relativity

Special relativity indicates that humans live in a four-dimensional space-time where the ‘distance’ ssbetween points in space-time can be regarded as:

\[\mathrm{ s } ^ { 2 } = - \mathrm { c } ^ { 2 } \Delta \mathrm { t } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { x } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm{ y } ^ { 2 } + \Delta \mathrm { z } ^ { 2 } = \mathrm{ X } ^ { \mathrm { T } } \eta \mathrm{ X }

The last equation is a matrix relation in which TT denotes transpose (for vectors \(\mathrm { A } ^ { \mathrm { T } } \mathrm { B } = \mathrm { A } \cdot \mathrm { B }\) ), \(\mathrm{X}\) is the vector \)( \mathrm { c } \Delta \mathrm { t } , \Delta \mathrm { x } , \Delta \mathrm { y } , \Delta \mathrm { z } )\), and \(\mathrm{η}\) is the matrix:

\[\eta = \left( \begin{array} { c c c c } { - 1 } & { 0 } & { 0 } & { 0 } \\ { 0 } & { 1 } & { 0 } & { 0 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 } & { 0 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right)\]

A matrix that goes in between two vectors to give a length is called a metric. In mathematics, a metric or distance function is a function which defines a distance between elements of a set. In this case, the set is the space-time and the elements are points in that space-time. A space-time with the ηη metric is called Minkowski space and ηη is the Minkowski metric.

Four-dimensional Minkowski space-time is only one of many different possible space-times (geometries) which differ in their metric matrix. An arbitrary metric matrix can be denoted as gg, raising questions as to what space-times with different metrics represent. In 1916, Einstein found the importance of these space-times in his theory of general relativity.

General Relativity

General relativity, or the general theory of relativity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1916. It is the current description of gravitation in modern physics. General relativity generalizes special relativity and Newton’s law of universal gravitation, providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time, or space-time. In particular, the curvature of space-time is directly related to the energy and momentum of whatever matter and radiation are present. The relation is specified by the Einstein field equations, a system of partial differential equations.

\[\text { g } \leftrightarrow \text { curvature } \leftrightarrow \text { Energy and Momentum }\]

People can use the metric to calculate curvature and then use the Einstein field equations to relate the curvature to the energy and momentum of the space-time. Going in the reverse order, energy and momentum affect the curvature and the space-time. Thus, energy and momentum curves space-time. Minkowski space is the special space devoid of matter, and as a result, it is completely flat. The precise definition of curvature requires knowledge of advanced mathematics, but an intuitive way to understand it is that the definition of a straight line changes in curved spacetime.

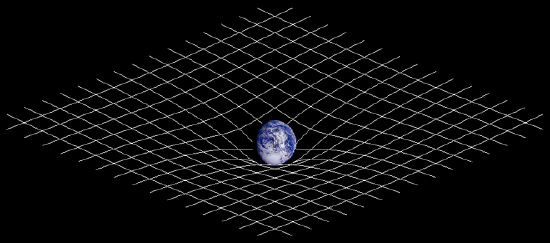

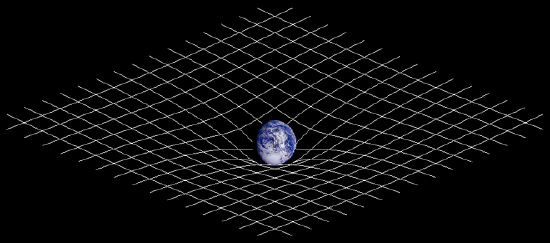

A pictorial example is shown in the figure below, where anything that is near the Earth has its motion altered due to the curved space-time. This altering of motion affects satellites, the moon, and even humans. If the space around the Earth were flat, humans would simply float away if they jumped upwards. Since the Earth alters the space-time, humans are pulled toward the Earth. In essence, gravity is a geometrical effect.

Curvature of space-time: The massive Earth is altering the curvature of space-time.

Key Points

- Time is relative.

- Lengths of moving objects are different than if their lengths were measured in a co-moving frame.

- Time and space are not independent.

- We live in a four-dimensional universe; the first three dimensions are spatial, and the fourth is time.

- The coordinate system of physical observers are related to one another via Lorentz transformations.

- Nothing can travel faster than the speed of light.

- The metric matrix can be used to calculate the curvature of space-time.

- Curvature can be related to energy and momentum via the Einstein equations.

- Due to the curvature of space-time, the motion of objects are altered near massive objects.

Key Terms

- special relativity: A theory that (neglecting the effects of gravity) reconciles the principle of relativity with the observation that the speed of light is constant in all frames of reference.

- time dilation: The slowing of the passage of time experienced by objects in motion relative to an observer; measurable only at relativistic speeds.

- length contraction: Observers measure a moving object’s length as being smaller than it would be if it were stationary.

- line element: An invariant quantity in special relativity

- Lorentz transformation: a transformation relating the spacetime coordinates of one frame of reference to another in special relativity

- relativity of simultaneity: For space-like separated space-time points, the time-ordering between events is relative.

- general relativity: A theory extending special relativity and uniformly accounting for gravity and accelerated frames of reference, postulating that space-time curves in the presence of mass.

- Minkowski space: A four dimensional flat space-time. Because it is flat, it is devoid of matter.

- metric: A metric, or distance function, is a function which defines a distance between elements of a set.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION