6.1.1: Simple Harmonic Motion

- Page ID

- 94647

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Define the terms period and frequency

- List the characteristics of simple harmonic motion

- Explain the concept of phase shift

- Write the equations of motion for the system of a mass and spring undergoing simple harmonic motion

- Describe the motion of a mass oscillating on a vertical spring

When you pluck a guitar string, the resulting sound has a steady tone and lasts a long time (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The string vibrates around an equilibrium position, and one oscillation is completed when the string starts from the initial position, travels to one of the extreme positions, then to the other extreme position, and returns to its initial position. We define periodic motion to be any motion that repeats itself at regular time intervals, such as exhibited by the guitar string or by a child swinging on a swing. In this section, we study the basic characteristics of oscillations and their mathematical description.

Period and Frequency in Oscillations

In the absence of friction, the time to complete one oscillation remains constant and is called the period (T). Its units are usually seconds, but may be any convenient unit of time. The word ‘period’ refers to the time for some event whether repetitive or not, but in this chapter, we shall deal primarily in periodic motion, which is by definition repetitive.

A concept closely related to period is the frequency of an event. Frequency (f) is defined to be the number of events per unit time. For periodic motion, frequency is the number of oscillations per unit time. The relationship between frequency and period is

\[f = \frac{1}{T} \ldotp \label{15.1}\]

The SI unit for frequency is the hertz (Hz) and is defined as one cycle per second:

\[1\; Hz = 1\; cycle/sec\; or\; 1\; Hz = \frac{1}{s} = 1\; s^{-1} \ldotp\]

A cycle is one complete oscillation

Ultrasound machines are used by medical professionals to make images for examining internal organs of the body. An ultrasound machine emits high-frequency sound waves, which reflect off the organs, and a computer receives the waves, using them to create a picture. We can use the formulas presented in this module to determine the frequency, based on what we know about oscillations. Consider a medical imaging device that produces ultrasound by oscillating with a period of 0.400 \(\mu\)s. What is the frequency of this oscillation?

Strategy

The period (T) is given and we are asked to find frequency (f).

Solution

Substitute 0.400 µs for T in f = \(\frac{1}{T}\):

\[f = \frac{1}{T} = \frac{1}{0.400 \times 10^{-6}\; s} \ldotp \nonumber\]

Solve to find

\[f = 2.50 \times 10^{6}\; Hz \ldotp \nonumber\]

Significance

This frequency of sound is much higher than the highest frequency that humans can hear (the range of human hearing is 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz); therefore, it is called ultrasound. Appropriate oscillations at this frequency generate ultrasound used for noninvasive medical diagnoses, such as observations of a fetus in the womb.

Characteristics of Simple Harmonic Motion

A very common type of periodic motion is called simple harmonic motion (SHM). A system that oscillates with SHM is called a simple harmonic oscillator.

In simple harmonic motion, the acceleration of the system, and therefore the net force, is proportional to the displacement and acts in the opposite direction of the displacement.

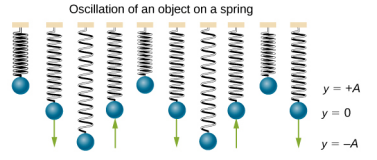

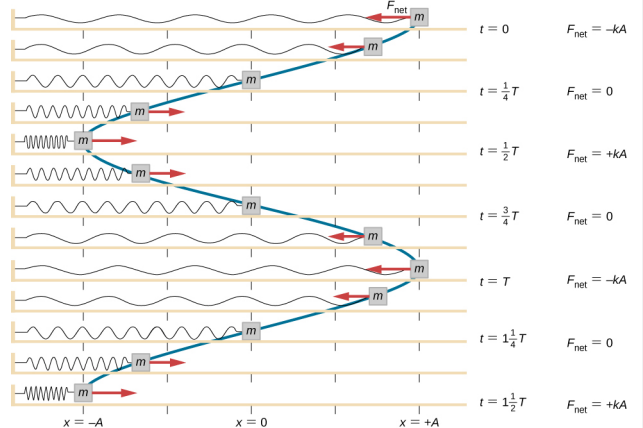

A good example of SHM is an object with mass \(m\) attached to a spring on a frictionless surface, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). The object oscillates around the equilibrium position, and the net force on the object is equal to the force provided by the spring. This force obeys Hooke’s law Fs = −kx, as discussed in a previous chapter.

If the net force can be described by Hooke’s law and there is no damping (slowing down due to friction or other nonconservative forces), then a simple harmonic oscillator oscillates with equal displacement on either side of the equilibrium position, as shown for an object on a spring in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). The maximum displacement from equilibrium is called the amplitude (A). The units for amplitude and displacement are the same but depend on the type of oscillation. For the object on the spring, the units of amplitude and displacement are meters.

What is so significant about SHM? For one thing, the period \(T\) and frequency \(f\) of a simple harmonic oscillator are independent of amplitude. The string of a guitar, for example, oscillates with the same frequency whether plucked gently or hard.

Two important factors do affect the period of a simple harmonic oscillator. The period is related to how stiff the system is. A very stiff object has a large force constant (k), which causes the system to have a smaller period. For example, you can adjust a diving board’s stiffness—the stiffer it is, the faster it vibrates, and the shorter its period. Period also depends on the mass of the oscillating system. The more massive the system is, the longer the period. For example, a heavy person on a diving board bounces up and down more slowly than a light one. In fact, the mass m and the force constant k are the only factors that affect the period and frequency of SHM. To derive an equation for the period and the frequency, we must first define and analyze the equations of motion. Note that the force constant is sometimes referred to as the spring constant.

Equations of SHM

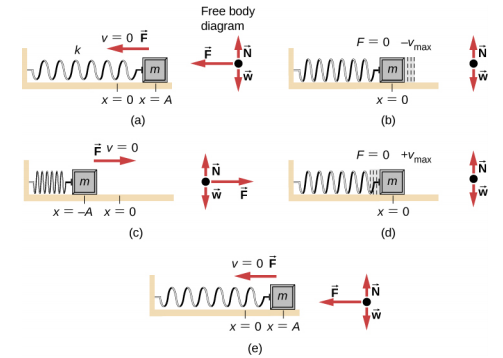

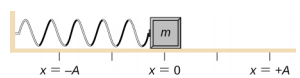

Consider a block attached to a spring on a frictionless table (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The equilibrium position (the position where the spring is neither stretched nor compressed) is marked as x = 0 . At the equilibrium position, the net force is zero.

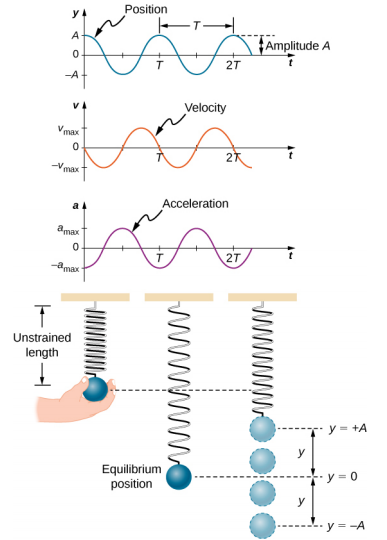

Work is done on the block to pull it out to a position of x = + A, and it is then released from rest. The maximum x-position (A) is called the amplitude of the motion. The block begins to oscillate in SHM between x = + A and x = −A, where A is the amplitude of the motion and T is the period of the oscillation. The period is the time for one oscillation. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the motion of the block as it completes one and a half oscillations after release.

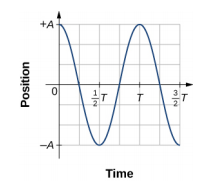

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows a plot of the position of the block versus time. When the position is plotted versus time, it is clear that the data can be modeled by a cosine function with an amplitude \(A\) and a period \(T\). The cosine function cos\(\theta\) repeats every multiple of 2\(\pi\), whereas the motion of the block repeats every period T. However, the function \(\cos \left(\dfrac{2 \pi}{T} t \right)\) repeats every integer multiple of the period. The maximum of the cosine function is one, so it is necessary to multiply the cosine function by the amplitude A.

\[x(t) = A \cos \left(\dfrac{2 \pi}{T} t \right) = A \cos (\omega t) \ldotp \label{15.2}\]

Recall from the chapter on rotation that the angular frequency equals \(\omega = \frac{d \theta}{dt}\). In this case, the period is constant, so the angular frequency is defined as 2\(\pi\) divided by the period, \(\omega = \frac{2 \pi}{T}\).

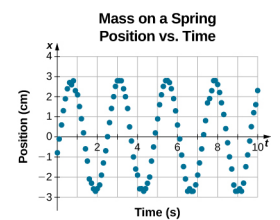

The equation for the position as a function of time \(x(t) = A\cos( \omega t)\) is good for modeling data, where the position of the block at the initial time t = 0.00 s is at the amplitude A and the initial velocity is zero. Often when taking experimental data, the position of the mass at the initial time t = 0.00 s is not equal to the amplitude and the initial velocity is not zero. Consider 10 seconds of data collected by a student in lab, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

The data in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) can still be modeled with a periodic function, like a cosine function, but the function is shifted to the right. This shift is known as a phase shift and is usually represented by the Greek letter phi (\(\phi\)). The equation of the position as a function of time for a block on a spring becomes

\[x(t) = A \cos (\omega t + \phi) \ldotp\]

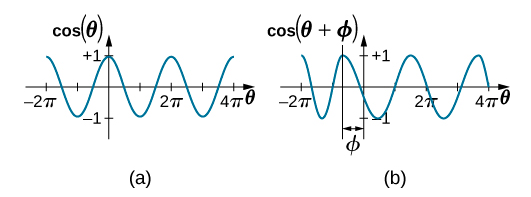

This is the generalized equation for SHM where t is the time measured in seconds, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency with units of inverse seconds, A is the amplitude measured in meters or centimeters, and \(\phi\) is the phase shift measured in radians (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). It should be noted that because sine and cosine functions differ only by a phase shift, this motion could be modeled using either the cosine or sine function.

The velocity of the mass on a spring, oscillating in SHM, can be found by taking the derivative of the position equation:

\[v(t) = \frac{dx}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt} (A \cos (\omega t + \phi)) = -A \omega \sin(\omega t + \varphi) = -v_{max} \sin (\omega t + \phi) \ldotp\]

Because the sine function oscillates between –1 and +1, the maximum velocity is the amplitude times the angular frequency, vmax = A\(\omega\). The maximum velocity occurs at the equilibrium position (x = 0) when the mass is moving toward x = + A. The maximum velocity in the negative direction is attained at the equilibrium position (x = 0) when the mass is moving toward x = −A and is equal to −vmax.

The acceleration of the mass on the spring can be found by taking the time derivative of the velocity:

\[a(t) = \frac{dv}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt} (-A \omega \sin (\omega t + \phi)) = -A \omega^{2} \cos (\omega t + \varphi) = -a_{max} \cos (\omega t + \phi) \ldotp\]

The maximum acceleration is amax = A\(\omega^{2}\). The maximum acceleration occurs at the position (x = −A), and the acceleration at the position (x = −A) and is equal to −amax.

Summary of Equations of Motion for SHM

In summary, the oscillatory motion of a block on a spring can be modeled with the following equations of motion:

\[ \begin{align} x(t) &= A \cos (\omega t + \phi) \label{15.3} \\[4pt] v(t) &= -v_{max} \sin (\omega t + \phi) \label{15.4} \\[4pt] a(t) &= -a_{max} \cos (\omega t + \phi) \label{15.5} \end{align}\]

with

\[ \begin{align} x_{max} &= A \label{15.6} \\[4pt] v_{max} &= A \omega \label{15.7} \\[4pt] a_{max} &= A \omega^{2} \ldotp \label{15.8} \end{align}\]

Here, \(A\) is the amplitude of the motion, \(T\) is the period, \(\phi\) is the phase shift, and \(\omega = \frac{2 \pi}{T}\) = 2\(\pi\)f is the angular frequency of the motion of the block.

A 2.00-kg block is placed on a frictionless surface. A spring with a force constant of k = 32.00 N/m is attached to the block, and the opposite end of the spring is attached to the wall. The spring can be compressed or extended. The equilibrium position is marked as x = 0.00 m. Work is done on the block, pulling it out to x = + 0.02 m. The block is released from rest and oscillates between x = + 0.02 m and x = −0.02 m. The period of the motion is 1.57 s. Determine the equations of motion.

Strategy

We first find the angular frequency. The phase shift is zero, \(\phi\) = 0.00 rad, because the block is released from rest at x = A = + 0.02 m. Once the angular frequency is found, we can determine the maximum velocity and maximum acceleration.

Solution

The angular frequency can be found and used to find the maximum velocity and maximum acceleration:

\[\begin{split} \omega & = \frac{2 \pi}{1.57\; s} = 4.00\; s^{-1}; \\ v_{max} & = A \omega = (0.02\; m)(4.00\; s^{-1}) = 0.08\; m/s; \\ a_{max} & = A \omega^{2} = (0.02; m)(4.00\; s^{-1})^{2} = 0.32\; m/s^{2} \ldotp \end{split}\]

All that is left is to fill in the equations of motion:

\[\begin{split} x(t) & = a \cos (\omega t + \phi) = (0.02\; m) \cos (4.00\; s^{-1} t); \\ v(t) & = -v_{max} \sin (\omega t + \phi) = (-0.8\; m/s) \sin (4.00\; s^{-1} t); \\ a(t) & = -a_{max} \cos (\omega t + \phi) = (-0.32\; m/s^{2}) \cos (4.00\; s^{-1} t) \ldotp \end{split}\]

Significance

The position, velocity, and acceleration can be found for any time. It is important to remember that when using these equations, your calculator must be in radians mode.

The Period and Frequency of a Mass on a Spring

One interesting characteristic of the SHM of an object attached to a spring is that the angular frequency, and therefore the period and frequency of the motion, depend on only the mass and the force constant, and not on other factors such as the amplitude of the motion. We can use the equations of motion and Newton’s second law (\(\vec{F}_{net} = m \vec{a}\)) to find equations for the angular frequency, frequency, and period.

Consider the block on a spring on a frictionless surface. There are three forces on the mass: the weight, the normal force, and the force due to the spring. The only two forces that act perpendicular to the surface are the weight and the normal force, which have equal magnitudes and opposite directions, and thus sum to zero. The only force that acts parallel to the surface is the force due to the spring, so the net force must be equal to the force of the spring:

\[\begin{split} F_{x} & = -kx; \\ ma & = -kx; \\ m \frac{d^{2} x}{dt^{2}} & = -kx; \\ \frac{d^{2} x}{dt^{2}} & = - \frac{k}{m} x \ldotp \end{split}\]

Substituting the equations of motion for x and a gives us

\[-A \omega^{2} \cos (\omega t + \phi) = - \frac{k}{m} A \cos (\omega t +\phi) \ldotp\]

Cancelling out like terms and solving for the angular frequency yields

\[\omega = \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}} \ldotp \label{15.9}\]

The angular frequency depends only on the force constant and the mass, and not the amplitude. The angular frequency is defined as \(\omega = \frac{2 \pi}{T}\), which yields an equation for the period of the motion:

\[T = 2 \pi \sqrt{\frac{m}{k}} \ldotp \label{15.10}\]

The period also depends only on the mass and the force constant. The greater the mass, the longer the period. The stiffer the spring, the shorter the period. The frequency is

\[f = \frac{1}{T} = \frac{1}{2 \pi} \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}} \ldotp \label{15.11}\]

Vertical Motion and a Horizontal Spring

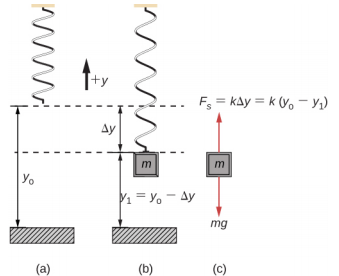

When a spring is hung vertically and a block is attached and set in motion, the block oscillates in SHM. In this case, there is no normal force, and the net effect of the force of gravity is to change the equilibrium position. Consider Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\). Two forces act on the block: the weight and the force of the spring. The weight is constant and the force of the spring changes as the length of the spring changes.

When the block reaches the equilibrium position, as seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\), the force of the spring equals the weight of the block, Fnet = Fs − mg = 0, where

\[-k (- \Delta y) = mg \ldotp\]

From the figure, the change in the position is \( \Delta y = y_{0}-y_{1} \) and since \(-k (- \Delta y) = mg\), we have

\[k (y_{0} - y_{1}) - mg = 0 \ldotp\]

If the block is displaced and released, it will oscillate around the new equilibrium position. As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\), if the position of the block is recorded as a function of time, the recording is a periodic function. If the block is displaced to a position y, the net force becomes Fnet = k(y0 - y) − mg. But we found that at the equilibrium position, mg = k\(\Delta\)y = ky0 − ky1. Substituting for the weight in the equation yields

\[F_{net} =ky_{0} - ky - (ky_{0} - ky_{1}) = k (y_{1} - y) \ldotp\]

Recall that y1 is just the equilibrium position and any position can be set to be the point y = 0.00 m. So let’s set y1 to y = 0.00 m. The net force then becomes

\[\begin{split}F_{net} & = -ky; \\ m \frac{d^{2} y}{dt^{2}} & = -ky \ldotp \end{split}\]

This is just what we found previously for a horizontally sliding mass on a spring. The constant force of gravity only served to shift the equilibrium location of the mass. Therefore, the solution should be the same form as for a block on a horizontal spring, y(t) = Acos(\(\omega\)t + \(\phi\)). The equations for the velocity and the acceleration also have the same form as for the horizontal case. Note that the inclusion of the phase shift means that the motion can actually be modeled using either a cosine or a sine function, since these two functions only differ by a phase shift.