16.3: Simple Harmonic Motion- A Special Periodic Motion

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe a simple harmonic oscillator.

- Explain the link between simple harmonic motion and waves.

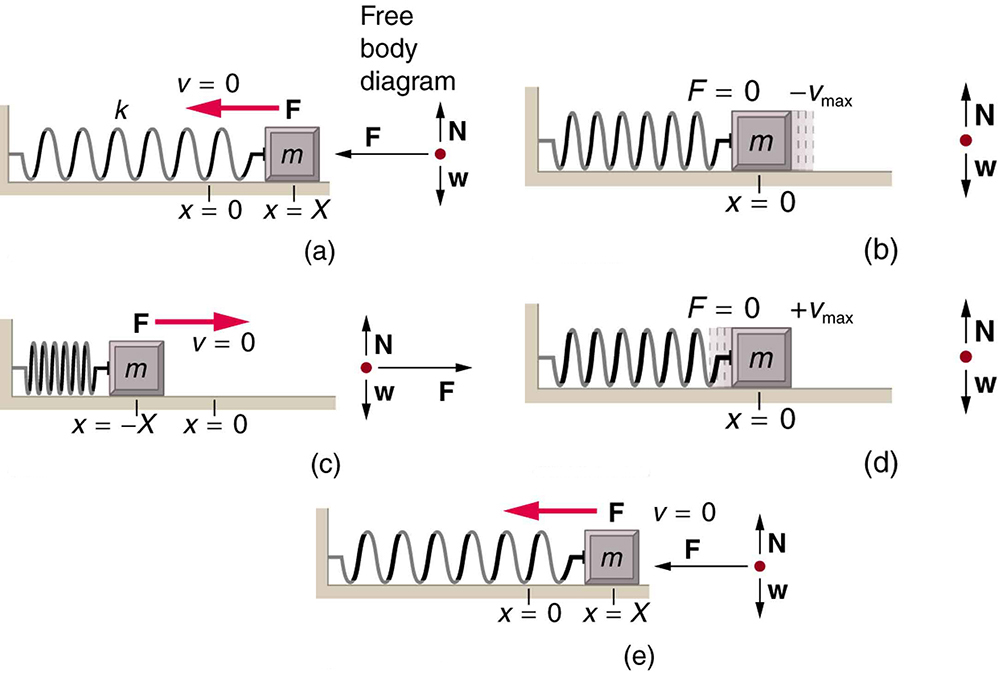

The oscillations of a system in which the net force can be described by Hooke’s law are of special importance, because they are very common. They are also the simplest oscillatory systems. Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) is the name given to oscillatory motion for a system where the net force can be described by Hooke’s law, and such a system is called a simple harmonic oscillator. If the net force can be described by Hooke’s law and there is no damping (by friction or other non-conservative forces), then a simple harmonic oscillator will oscillate with equal displacement on either side of the equilibrium position, as shown for an object on a spring in Figure 16.3.1. The maximum displacement from equilibrium is called the amplitude X. The units for amplitude and displacement are the same, but depend on the type of oscillation. For the object on the spring, the units of amplitude and displacement are meters; whereas for sound oscillations, they have units of pressure (and other types of oscillations have yet other units). Because amplitude is the maximum displacement, it is related to the energy in the oscillation.

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: SHM AND THE MARBLE

Find a bowl or basin that is shaped like a hemisphere on the inside. Place a marble inside the bowl and tilt the bowl periodically so the marble rolls from the bottom of the bowl to equally high points on the sides of the bowl. Get a feel for the force required to maintain this periodic motion. What is the restoring force and what role does the force you apply play in the simple harmonic motion (SHM) of the marble?

What is so significant about simple harmonic motion? One special thing is that the period T and frequency f of a simple harmonic oscillator are independent of amplitude. The string of a guitar, for example, will oscillate with the same frequency whether plucked gently or hard. Because the period is constant, a simple harmonic oscillator can be used as a clock.

Two important factors do affect the period of a simple harmonic oscillator. The period is related to how stiff the system is. A very stiff object has a large force constant k, which causes the system to have a smaller period. For example, you can adjust a diving board’s stiffness—the stiffer it is, the faster it vibrates, and the shorter its period. Period also depends on the mass of the oscillating system. The more massive the system is, the longer the period. For example, a heavy person on a diving board bounces up and down more slowly than a light one.

In fact, the mass m and the force constant k are the only factors that affect the period and frequency of simple harmonic motion.

Period of Simple Harmonic Oscillator

The period of a simple harmonic oscillator is given by

T=2π√mk

and, because f=1/T, the frequency of a simple harmonic oscillator is

f=12π√km.

Note that neither T nor f has any dependence on amplitude.

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: MASS AND RULER OSCILLATIONS

Find two identical wooden or plastic rulers. Tape one end of each ruler firmly to the edge of a table so that the length of each ruler that protrudes from the table is the same. On the free end of one ruler tape a heavy object such as a few large coins. Pluck the ends of the rulers at the same time and observe which one undergoes more cycles in a time period, and measure the period of oscillation of each of the rulers.

Example 16.3.1: Calculate the Frequency and Period of Oscillations: Bad Shock Absorbers in a Car

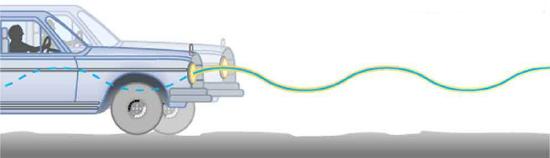

If the shock absorbers in a car go bad, then the car will oscillate at the least provocation, such as when going over bumps in the road and after stopping (See Figure 16.3.2). Calculate the frequency and period of these oscillations for such a car if the car’s mass (including its load) is 900 kg and the force constant k of the suspension system is 6.53×104N/m.

Strategy

The frequency of the car’s oscillations will be that of a simple harmonic oscillator as given in the equation f=12π√km.

The mass and the force constant are both given.

Solution

- Enter the known values of k and m: f=12π√km=12π√6.53×104N/m900kg.

- Calculate the frequency: 12π√72.6/s−2=1.3656/s−1≈1.36/s−1=1.36Hz

- You could use T=2π√mk to calculate the period, but it is simpler to use the relationship T=1/f and substitute the value just found for f: T=1f=11.356Hz=0.738s.

Discussion

The values of T and f both seem about right for a bouncing car. You can observe these oscillations if you push down hard on the end of a car and let go.

The Link between Simple Harmonic Motion and Waves

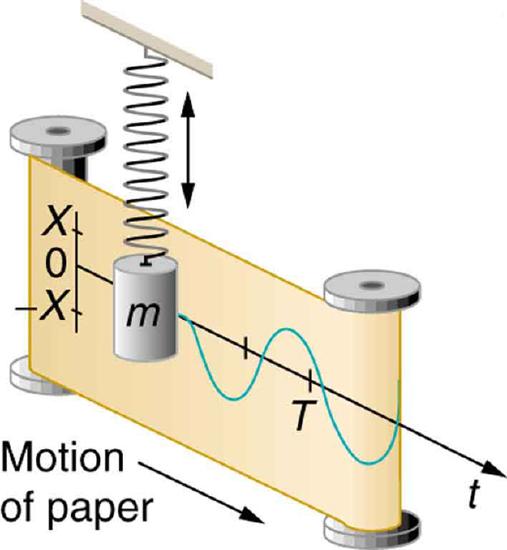

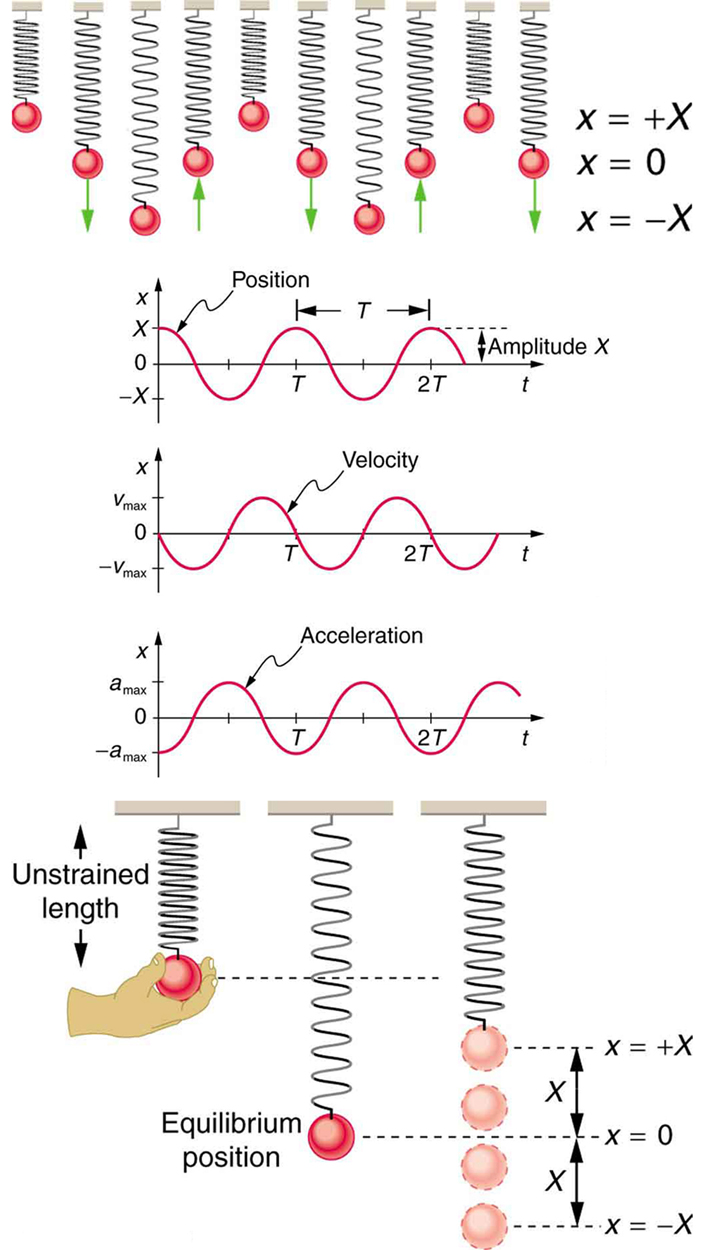

If a time-exposure photograph of the bouncing car were taken as it drove by, the headlight would make a wavelike streak, as shown in Figure 16.3.2. Similarly, Figure 16.3.3 shows an object bouncing on a spring as it leaves a wavelike "trace of its position on a moving strip of paper. Both waves are sine functions. All simple harmonic motion is intimately related to sine and cosine waves.

The displacement as a function of time t in any simple harmonic motion—that is, one in which the net restoring force can be described by Hooke’s law, is given by

x(t)=Xcos2πtT,

where X is amplitude. At T=0, the initial position is x0=X, and the displacement oscillates back and forth with a period T. (When t=T, we get x=X again because cos2π=1). Furthermore, from this expression for x, the velocity v as a function of time is given by:

v(t)=−vmaxsin(2πtT),

where vmax=2πX/T=X√k/m. The object has zero velocity at maximum displacement—for example, v=0 when t=0, and at that time x=X. The minus sign in the first equation for v(t) gives the correct direction for the velocity. Just after the start of the motion, for instance, the velocity is negative because the system is moving back toward the equilibrium point. Finally, we can get an expression for acceleration using Newton’s second law. [Then we have x(t),v(t),t, and a(t), the quantities needed for kinematics and a description of simple harmonic motion.] According to Newton’s second law, the acceleration is a=F/m=kx/m. So, a(t) is also a cosine function:

a(t)=−kXmcos2πtT.

Hence, a(t) is directly proportional to and in the opposite direction to x(t). Figure 16.3.4 shows the simple harmonic motion of an object on a spring and presents graphs of x(t), v(t), and a(t) versus time.

The most important point here is that these equations are mathematically straightforward and are valid for all simple harmonic motion. They are very useful in visualizing waves associated with simple harmonic motion, including visalizing how waves add with one another.

Exercise 16.3.1

Suppose you pluck a banjo string. You hear a single note that starts out loud and slowly quiets over time. Describe what happens to the sound waves in terms of period, frequency and amplitude as the sound decreases in volume.

- Answer

-

Frequency and period remain essentially unchanged. Only amplitude decreases as volume decreases.

Exercise 16.3.2

A babysitter is pushing a child on a swing. At the point where the swing reaches x, where would the corresponding point on a wave of this motion be located?

- Answer

-

x is the maximum deformation, which corresponds to the amplitude of the wave. The point on the wave would either be at the very top or the very bottom of the curve.

PHET EXPLORATIONS: MASSES AND STRINGS

A realistic mass and spring laboratory. Hang masses from springs and adjust the spring stiffness and damping. You can even slow time. Transport the lab to different planets. A chart shows the kinetic, potential, and thermal energy for each spring.

Summary

- Simple harmonic motion is oscillatory motion for a system that can be described only by Hooke’s law. Such a system is also called a simple harmonic oscillator.

- Maximum displacement is the amplitude X. The period T and frequency f of a simple harmonic oscillator are given by T=2π√mk and f=12π√km, where m is the mass of the system.

- Displacement in simple harmonic motion as a function of time is given by x=Xcos2πtT.

- The velocity is given by v(t)=−vmaxsin2πtT, where vmax=√k/mX.

- The acceleration is found to be a=−kXmcos2πtT.

Glossary

- amplitude

- the maximum displacement from the equilibrium position of an object oscillating around the equilibrium position

- simple harmonic motion

- the oscillatory motion in a system where the net force can be described by Hooke’s law

- simple harmonic oscillator

- a device that implements Hooke’s law, such as a mass that is attached to a spring, with the other end of the spring being connected to a rigid support such as a wall