18.3: Diameters of Stars

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the methods used to determine star diameters

- Identify the parts of an eclipsing binary star light curve that correspond to the diameters of the individual components

It is easy to measure the diameter of the Sun. Its angular diameter—that is, its apparent size on the sky—is about 1/2°. If we know the angle the Sun takes up in the sky and how far away it is, we can calculate its true (linear) diameter, which is 1.39 million kilometers, or about 109 times the diameter of Earth.

Unfortunately, the Sun is the only star whose angular diameter is easily measured. All the other stars are so far away that they look like pinpoints of light through even the largest ground-based telescopes. (They often seem to be bigger, but that is merely distortion introduced by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere.) Luckily, there are several techniques that astronomers can use to estimate the sizes of stars.

Stars Blocked by the Moon

One technique, which gives very precise diameters but can be used for only a few stars, is to observe the dimming of light that occurs when the Moon passes in front of a star. What astronomers measure (with great precision) is the time required for the star’s brightness to drop to zero as the edge of the Moon moves across the star’s disk. Since we know how rapidly the Moon moves in its orbit around Earth, it is possible to calculate the angular diameter of the star. If the distance to the star is also known, we can calculate its diameter in kilometers. This method works only for fairly bright stars that happen to lie along the zodiac, where the Moon (or, much more rarely, a planet) can pass in front of them as seen from Earth.

Eclipsing Binary Stars

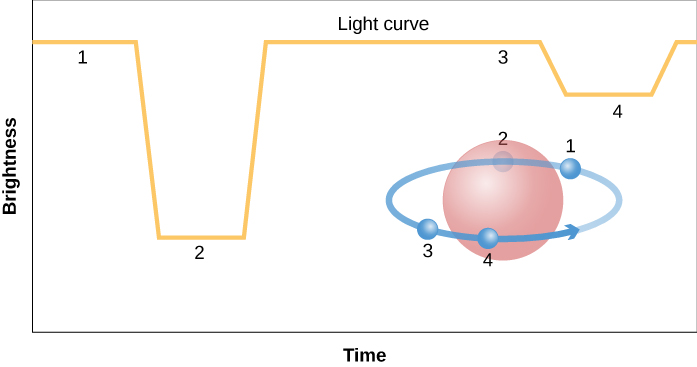

Accurate sizes for a large number of stars come from measurements of eclipsing binary star systems, and so we must make a brief detour from our main story to examine this type of star system. Some binary stars are lined up in such a way that, when viewed from Earth, each star passes in front of the other during every revolution (Figure 18.3.1). When one star blocks the light of the other, preventing it from reaching Earth, the luminosity of the system decreases, and astronomers say that an eclipse has occurred.

The discovery of the first eclipsing binary helped solve a long-standing puzzle in astronomy. The star Algol, in the constellation of Perseus, changes its brightness in an odd but regular way. Normally, Algol is a fairly bright star, but at intervals of 2 days, 20 hours, 49 minutes, it fades to one-third of its regular brightness. After a few hours, it brightens to normal again. This effect is easily seen, even without a telescope, if you know what to look for.

In 1783, a young English astronomer named John Goodricke (1764–1786) made a careful study of Algol (see the feature on John Goodricke in Section 19.3 for a discussion of his life and work). Even though Goodricke could neither hear nor speak, he made a number of major discoveries in the 21 years of his brief life. He suggested that Algol’s unusual brightness variations might be due to an invisible companion that regularly passes in front of the brighter star and blocks its light. Unfortunately, Goodricke had no way to test this idea, since it was not until about a century later that equipment became good enough to measure Algol’s spectrum.

In 1889, the German astronomer Hermann Vogel (1841–1907) demonstrated that, like Mizar, Algol is a spectroscopic binary. The spectral lines of Algol were not observed to be double because the fainter star of the pair gives off too-little light compared with the brighter star for its lines to be conspicuous in the composite spectrum. Nevertheless, the periodic shifting back and forth of the brighter star’s lines gave evidence that it was revolving about an unseen companion. (The lines of both components need not be visible for a star to be recognized as a spectroscopic binary.)

The discovery that Algol is a spectroscopic binary verified Goodricke’s hypothesis. The plane in which the stars revolve is turned nearly edgewise to our line of sight, and each star passes in front of the other during every revolution. (The eclipse of the fainter star in the Algol system is not very noticeable because the part of it that is covered contributes little to the total light of the system. This second eclipse can, however, be detected by careful measurements.)

Any binary star produces eclipses if viewed from the proper direction, near the plane of its orbit, so that one star passes in front of the other (see Figure 18.3.1). But from our vantage point on Earth, only a few binary star systems are oriented in this way.

ASTRONOMY AND MYTHOLOGY: ALGOL THE DEMON STAR AND PERSEUS THE HERO

The name Algol comes from the Arabic Ras al Ghul, meaning “the demon’s head.”1 The word “ghoul” in English has the same derivation. As discussed in Observing the Sky: The Birth of Astronomy, many of the bright stars have Arabic names because during the long dark ages in medieval Europe, it was Arabic astronomers who preserved and expanded the Greek and Roman knowledge of the skies. The reference to the demon is part of the ancient Greek legend of the hero Perseus, who is commemorated by the constellation in which we find Algol and whose adventures involve many of the characters associated with the northern constellations.

Perseus was one of the many half-god heroes fathered by Zeus (Jupiter in the Roman version), the king of the gods in Greek mythology. Zeus had, to put it delicately, a roving eye and was always fathering somebody or other with a human maiden who caught his fancy. (Perseus derives from Per Zeus, meaning “fathered by Zeus.”) Set adrift with his mother by an (understandably) upset stepfather, Perseus grew up on an island in the Aegean Sea. The king there, taking an interest in Perseus’ mother, tried to get rid of the young man by assigning him an extremely difficult task.

In a moment of overarching pride, a beautiful young woman named Medusa had compared her golden hair to that of the goddess Athena (Minerva for the Romans). The Greek gods did not take kindly to being compared to mere mortals, and Athena turned Medusa into a gorgon: a hideous, evil creature with writhing snakes for hair and a face that turned anyone who looked at it into stone. Perseus was given the task of slaying this demon, which seemed like a pretty sure way to get him out of the way forever.

But because Perseus had a god for a father, some of the other gods gave him tools for the job, including Athena’s reflective shield and the winged sandals of Hermes (Mercury in the Roman story). By flying over her and looking only at her reflection, Perseus was able to cut off Medusa’s head without ever looking at her directly. Taking her head (which, conveniently, could still turn onlookers to stone even without being attached to her body) with him, Perseus continued on to other adventures.

He next came to a rocky seashore, where boasting had gotten another family into serious trouble with the gods. Queen Cassiopeia had dared to compare her own beauty to that of the Nereids, sea nymphs who were daughters of Poseidon (Neptune in Roman mythology), the god of the sea. Poseidon was so offended that he created a sea-monster named Cetus to devastate the kingdom. King Cepheus, Cassiopeia’s beleaguered husband, consulted the oracle, who told him that he must sacrifice his beautiful daughter Andromeda to the monster.

When Perseus came along and found Andromeda chained to a rock near the sea, awaiting her fate, he rescued her by turning the monster to stone. (Scholars of mythology actually trace the essence of this story back to far-older legends from ancient Mesopotamia, in which the god-hero Marduk vanquishes a monster named Tiamat. Symbolically, a hero like Perseus or Marduk is usually associated with the Sun, the monster with the power of night, and the beautiful maiden with the fragile beauty of dawn, which the Sun releases after its nightly struggle with darkness.)

Many of the characters in these Greek legends can be found as constellations in the sky, not necessarily resembling their namesakes but serving as reminders of the story. For example, vain Cassiopeia is sentenced to be very close to the celestial pole, rotating perpetually around the sky and hanging upside down every winter. The ancients imagined Andromeda still chained to her rock (it is much easier to see the chain of stars than to recognize the beautiful maiden in this star grouping). Perseus is next to her with the head of Medusa swinging from his belt. Algol represents this gorgon head and has long been associated with evil and bad fortune in such tales. Some commentators have speculated that the star’s change in brightness (which can be observed with the unaided eye) may have contributed to its unpleasant reputation, with the ancients regarding such a change as a sort of evil “wink.”

Diameters of Eclipsing Binary Stars

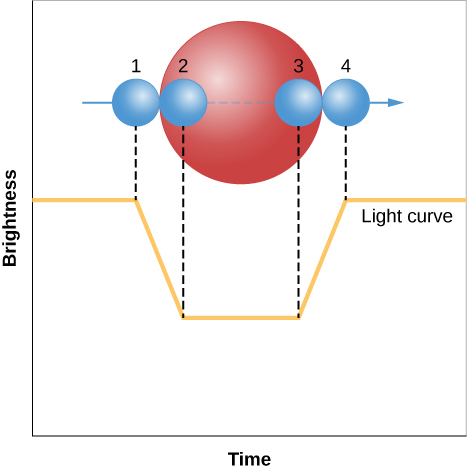

We now turn back to the main thread of our story to discuss how all this can be used to measure the sizes of stars. The technique involves making a light curve of an eclipsing binary, a graph that plots how the brightness changes with time. Let us consider a hypothetical binary system in which the stars are very different in size, like those illustrated in Figure 18.3.2. To make life easy, we will assume that the orbit is viewed exactly edge-on.

Even though we cannot see the two stars separately in such a system, the light curve can tell us what is happening. When the smaller star just starts to pass behind the larger star (a point we call first contact), the brightness begins to drop. The eclipse becomes total (the smaller star is completely hidden) at the point called second contact. At the end of the total eclipse (thirdcontact), the smaller star begins to emerge. When the smaller star has reached last contact, the eclipse is completely over.

To see how this allows us to measure diameters, look carefully at Figure 18.3.2. During the time interval between the first and second contacts, the smaller star has moved a distance equal to its own diameter. During the time interval from the first to third contacts, the smaller star has moved a distance equal to the diameter of the larger star. If the spectral lines of both stars are visible in the spectrum of the binary, then the speed of the smaller star with respect to the larger one can be measured from the Doppler shift. But knowing the speed with which the smaller star is moving and how long it took to cover some distance can tell the span of that distance—in this case, the diameters of the stars. The speed multiplied by the time interval from the first to second contact gives the diameter of the smaller star. We multiply the speed by the time between the first and third contacts to get the diameter of the larger star.

In actuality, the situation with eclipsing binaries is often a bit more complicated: orbits are generally not seen exactly edge-on, and the light from each star may be only partially blocked by the other. Furthermore, binary star orbits, just like the orbits of the planets, are ellipses, not circles. However, all these effects can be sorted out from very careful measurements of the light curve.

Using the Radiation Law to Get the Diameter

Another method for measuring star diameters makes use of the Stefan-Boltzmann law for the relationship between energy radiated and temperature (see Radiation and Spectra). In this method, the energy flux (energy emitted per second per square meter by a blackbody, like the Sun) is given by

F=σT4

where σ is a constant and T is the temperature. The surface area of a sphere (like a star) is given by

A=4πR2

The luminosity (L) of a star is then given by its surface area in square meters times the energy flux:

L=(A×F)

Previously, we determined the masses of the two stars in the Sirius binary system. Sirius gives off 8200 times more energy than its fainter companion star, although both stars have nearly identical temperatures. The extremely large difference in luminosity is due to the difference in radius, since the temperatures and hence the energy fluxes for the two stars are nearly the same. To determine the relative sizes of the two stars, we take the ratio of the corresponding luminosities:

LSiriusLcompanion=(ASirius×FSirius)(Acompanion×Fcompanion)=ASiriusAcompanion=4πR2Sirius4πR2companion=R2SiriusR2companionLSiriusLcompanion=8200=R2SiriusR2companion

Therefore, the relative sizes of the two stars can be found by taking the square root of the relative luminosity. Since √8200=91, the radius of Sirius is 91 times larger than the radium of its faint companion.

The method for determining the radius shown here requires both stars be visible, which is not always the case.

Stellar Diameters

The results of many stellar size measurements over the years have shown that most nearby stars are roughly the size of the Sun, with typical diameters of a million kilometers or so. Faint stars, as we might have expected, are generally smaller than more luminous stars. However, there are some dramatic exceptions to this simple generalization.

A few of the very luminous stars, those that are also red (indicating relatively low surface temperatures), turn out to be truly enormous. These stars are called, appropriately enough, giant stars or supergiant stars. An example is Betelgeuse, the second brightest star in the constellation of Orion and one of the dozen brightest stars in our sky. Its diameter, remarkably, is greater than 10 AU (1.5 billion kilometers!), large enough to fill the entire inner solar system almost as far out as Jupiter. In Stars from Adolescence to Old Age, we will look in detail at the evolutionary process that leads to the formation of such giant and supergiant stars.

Watch this star size comparison video for a striking visual that highlights the size of stars versus planets and the range of sizes among stars.

Summary

The diameters of stars can be determined by measuring the time it takes an object (the Moon, a planet, or a companion star) to pass in front of it and block its light. Diameters of members of eclipsing binary systems (where the stars pass in front of each other) can be determined through analysis of their orbital motions.

Footnotes

3Fans of Batman comic books and movies will recognize that this name was given to an archvillain in the series.

Glossary

- eclipsing binary

- a binary star in which the plane of revolution of the two stars is nearly edge-on to our line of sight, so that the light of one star is periodically diminished by the other passing in front of it