4.4: The Paraboloid

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

The Equation x2=4qz=2lz is a parabola in the xz-plane. The distance between vertex and focus is q, and the length of the semi latus rectum l=2q. The Equation can also be written

x2a2=zh

Here a and h are distances such that x=a when z=h, and the length of the semi latus rectum is l=a2/(2h).

If this parabola is rotated through 360∘ about the z-axis, the figure swept out is a paraboloid of revolution, or circular paraboloid. Many telescope mirrors are of this shape. The Equation to the circular paraboloid is

x2a2+y2a2=zh.

The cross-section at z=h is a circle of radius a.

The Equation x2a2+y2b2=zh,

in which we shall choose the x- and y-axes such that a>b, is an elliptic paraboloid and, if a≠b, is not formed by rotation of a parabola. At z=h, the cross section is an ellipse of semi major and minor axes equal to a and b respectively. The section in the plane y=0 is a parabola of semi latus rectum a2/(2h). The section in the plane x=0 is a parabola of semi latus rectum b2/(2h). The elliptic paraboloid lies entirely above the xy-plane.

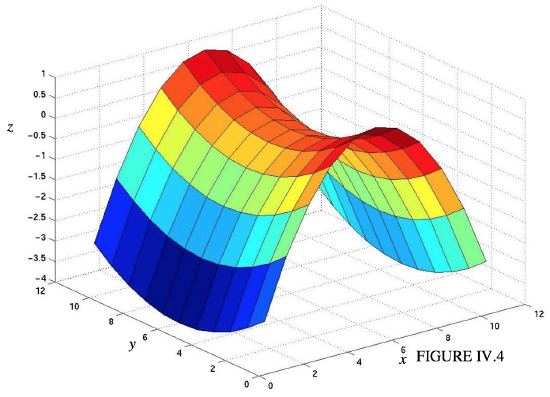

The Equation

x2a2−y2b2=zh

is a hyperbolic paraboloid, and its shape is not quite so easily visualized. Unlike the elliptic paraboloid, it extends above and below the plane. It is a saddle-shaped surface, with the saddle point at the origin. The section in the plane y=0 is the "nose down" parabola x2=a2z/h extending above the xy-plane. The section in the plane x=0 is the "nose up" parabola y2=−b2z/h extending below the xy-plane. The section in the plane z=h is the hyperbola

x2a2−y2b2=1.

The section with the plane z=−h is the conjugate hyperbola

x2a2−y2b2=−1.

The section with the plane z=0 is the asymptotes

x2a2−y2b2=0.

The surface for a=3, b=2, h=1 is drawn in figure IV.4.