13.2: Thermal Expansion of Solids and Liquids

- Page ID

- 1580

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and describe thermal expansion.

- Calculate the linear expansion of an object given its initial length, change in temperature, and coefficient of linear expansion.

- Calculate the volume expansion of an object given its initial volume, change in temperature, and coefficient of volume expansion.

- Calculate thermal stress on an object given its original volume, temperature change, volume change, and bulk modulus.

The expansion of alcohol in a thermometer is one of many commonly encountered examples of thermal expansion, the change in size or volume of a given mass with temperature. Hot air rises because its volume increases, which causes the hot air’s density to be smaller than the density of surrounding air, causing a buoyant (upward) force on the hot air. The same happens in all liquids and gases, driving natural heat transfer upwards in homes, oceans, and weather systems. Solids also undergo thermal expansion. Railroad tracks and bridges, for example, have expansion joints to allow them to freely expand and contract with temperature changes.

What are the basic properties of thermal expansion? First, thermal expansion is clearly related to temperature change. The greater the temperature change, the more a bimetallic strip will bend. Second, it depends on the material. In a thermometer, for example, the expansion of alcohol is much greater than the expansion of the glass containing it.

What is the underlying cause of thermal expansion? As is discussed in Kinetic Theory: Atomic and Molecular Explanation of Pressure and Temperature, an increase in temperature implies an increase in the kinetic energy of the individual atoms. In a solid, unlike in a gas, the atoms or molecules are closely packed together, but their kinetic energy (in the form of small, rapid vibrations) pushes neighboring atoms or molecules apart from each other. This neighbor-to-neighbor pushing results in a slightly greater distance, on average, between neighbors, and adds up to a larger size for the whole body. For most substances under ordinary conditions, there is no preferred direction, and an increase in temperature will increase the solid’s size by a certain fraction in each dimension.

Linear Thermal Expansion—Thermal Expansion in One Dimension

The change in length \(\Delta L\) is proportional to length \(L\). The dependence of thermal expansion on temperature, substance, and length is summarized in the equation

\[\Delta L = \alpha L \Delta T, \label{linear}\]

where \(\Delta L\) is the change in length \(L\), \(\Delta T\) is the change in temperature, and \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of linear expansion, which varies slightly with temperature.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists representative values of the coefficient of linear expansion, which may have units of \(1/^oC\) or 1/K. Because the size of a kelvin and a degree Celsius are the same, both \(\alpha\) and \(\Delta T\) can be expressed in units of kelvins or degrees Celsius. The equation \(\Delta L = \alpha L \Delta T\) is accurate for small changes in temperature and can be used for large changes in temperature if an average value of \(\alpha\) is used.

| Material | Coefficient of linear expansion (\(\alpha (1/^oC)\)) | Coefficient of volume expansion (\(\beta (1/^oC)\)) |

|---|---|---|

| Solids | ||

| Aluminum | \(25 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(75 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Brass | \(19 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(56 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Copper | \(17 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(51 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Gold | \(14 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(42 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Iron or Steel | \(12 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(35 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Invar (Nickel-Iron alloy) | \(0.9 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(2.7 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Lead | \(29 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(87 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Silver | \(18 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(54 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Glass (ordinary) | \(9 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(27 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Glass (Pyrex) | \(3 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(9 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Quartz | \(0.4 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(1 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Concrete, Brick | \(\approx 12 \times 10^{-6}\) | \(\approx 36 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Marble (average) | \(7 \times 10^{-6}\) | |

| Liquids | ||

| Ether | N/A | \(1650 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Ethyl alcohol | N/A | \(1100 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Petrol | N/A | \(950 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Glycerin | N/A | \(500 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Mercury | N/A | \(180 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Water | N/A | \(210 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Gases | ||

| Air and most other gases at atm | N/A | \(3400 \times 10^{-6}\) |

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Linear Thermal Expansion of The Golden Gate Bridge

The main span of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge is 1275 m long at its coldest. The bridge is exposed to temperatures ranging from \(-15^oC\) to \(40^oC\). What is its change in length between these temperatures? Assume that the bridge is made entirely of steel.

Strategy

Use the equation for linear thermal expansion (Equation \ref{linear}) to calculate the change in length, \(\Delta L\). Use the coefficient of linear expansion, \(\alpha\), for steel from Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), and note that the change in temperature, \(\Delta T\), is \(55^oC\).

Solution

Plug all of the known values into the equation to solve for \(\Delta L\).

\[ \begin{align*} \Delta L &= \alpha L \Delta T \\[5pt] &= \left(\dfrac{12 \times 10^{-6}}{^oC}\right) (1275 \, m)(55^oC) \\[5pt] &= 0.84 \, m \end{align*} \]

Discussion

Although not large compared with the length of the bridge, this change in length is observable. It is generally spread over many expansion joints so that the expansion at each joint is small.

Thermal Expansion in Two and Three Dimensions

Objects expand in all dimensions, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). That is, their areas and volumes, as well as their lengths, increase with temperature. Holes also get larger with temperature. If you cut a hole in a metal plate, the remaining material will expand exactly as it would if the plug was still in place. The plug would get bigger, and so the hole must get bigger too. (Think of the ring of neighboring atoms or molecules on the wall of the hole as pushing each other farther apart as temperature increases. Obviously, the ring of neighbors must get slightly larger, so the hole gets slightly larger).

Thermal Expansion in Two Dimensions

For small temperature changes, the change in area \(\Delta A\) is given by

\[\Delta A = 2 \alpha A \Delta T,\]

where \(\Delta A\) is the change in area \(A\), \(\Delta T\) is the change in temperature, and \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of linear expansion, which varies slightly with temperature.

Thermal Expansion in Three Dimensions

The change in volume \(\Delta V\) is very nearly \(\Delta V = 3\alpha V \Delta T\). This equation is usually written as

\[\Delta V = \beta V \Delta T, \label{volume}\]

where \(\beta\) is the coefficient of volume expansion and \(\beta \approx 3\alpha\). Note that the values of \(\beta\) in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) are almost exactly equal to \(3\alpha\).

In general, objects will expand with increasing temperature. Water is the most important exception to this rule. Water expands with increasing temperature (its density decreases) when it is at temperatures greater than \(4^oC(40^oF)\). However, it expands with decreasing temperature when it is between \(+4^oC\) and \(0^oC(40^oF\) to \(32^oF)\). Water is densest at \(+4^oC\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Perhaps the most striking effect of this phenomenon is the freezing of water in a pond. When water near the surface cools down to \(4^oC\) it is denser than the remaining water and thus will sink to the bottom. This “turnover” results in a layer of warmer water near the surface, which is then cooled. Eventually the pond has a uniform temperature of \(4^oC\). If the temperature in the surface layer drops below \(4^oC\), the water is less dense than the water below, and thus stays near the top. As a result, the pond surface can completely freeze over. The ice on top of liquid water provides an insulating layer from winter’s harsh exterior air temperatures. Fish and other aquatic life can survive in \(4^oC\) water beneath ice, due to this unusual characteristic of water. It also produces circulation of water in the pond that is necessary for a healthy ecosystem of the body of water.

Real-World Connections - Filling the Tank

Differences in the thermal expansion of materials can lead to interesting effects at the gas station. One example is the dripping of gasoline from a freshly filled tank on a hot day. Gasoline starts out at the temperature of the ground under the gas station, which is cooler than the air temperature above. The gasoline cools the steel tank when it is filled. Both gasoline and steel tank expand as they warm to air temperature, but gasoline expands much more than steel, and so it may overflow.

This difference in expansion can also cause problems when interpreting the gasoline gauge. The actual amount (mass) of gasoline left in the tank when the gauge hits “empty” is a lot less in the summer than in the winter. The gasoline has the same volume as it does in the winter when the “add fuel” light goes on, but because the gasoline has expanded, there is less mass. If you are used to getting another 40 miles on “empty” in the winter, beware—you will probably run out much more quickly in the summer.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Calculating Thermal Expansion: Gas vs. Gas Tank

Suppose your 60.0-L (15.9-gal) steel gasoline tank is full of gas, so both the tank and the gasoline have a temperature of \(15^oC\). How much gasoline has spilled by the time they warm to \(35.0^oC\)?

Strategy

The tank and gasoline increase in volume, but the gasoline increases more, so the amount spilled is the difference in their volume changes. (The gasoline tank can be treated as solid steel.) We can use the equation for volume expansion to calculate the change in volume of the gasoline and of the tank.

Solution

1. Use the equation for volume expansion (Equation \ref{volume}) to calculate the increase in volume of the steel tank:

\[\Delta V_s = \beta_s V_s \Delta T. \nonumber\]

2. The increase in volume of the gasoline is given by this equation:

\[\Delta V_{gas} = \beta_{gas} V_{gas} \Delta T. \nonumber\]

3. Find the difference in volume to determine the amount spilled as

\[V_{spill} = \Delta V_{gas} - \Delta V_S. \nonumber\]

Alternatively, we can combine these three equations into a single equation. (Note that the original volumes are equal.)

\[ \begin{align*} V_{spill} &= (\beta_{gas} - \beta_s)V \Delta T \\[5pt] &= [(950 - 35) \times 10^{-6} /^oC] (60.0 \, L)(20.0^oC) \\[5pt] &= 1.10 \, L. \end{align*} \]

Discussion

This amount is significant, particularly for a 60.0-L tank. The effect is so striking because the gasoline and steel expand quickly. The rate of change in thermal properties is discussed in Heat and Heat Transfer Methods.

If you try to cap the tank tightly to prevent overflow, you will find that it leaks anyway, either around the cap or by bursting the tank. Tightly constricting the expanding gas is equivalent to compressing it, and both liquids and solids resist being compressed with extremely large forces. To avoid rupturing rigid containers, these containers have air gaps, which allow them to expand and contract without stressing them.

Thermal Stress

Thermal stress is created by thermal expansion or contraction (see Elasticity: Stress and Strain for a discussion of stress and strain). Thermal stress can be destructive, such as when expanding gasoline ruptures a tank. It can also be useful, for example, when two parts are joined together by heating one in manufacturing, then slipping it over the other and allowing the combination to cool. Thermal stress can explain many phenomena, such as the weathering of rocks and pavement by the expansion of ice when it freezes.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Calculating Thermal Stress - Gas Pressure

What pressure would be created in the gasoline tank considered in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\), if the gasoline increases in temperature from \(15.0^oC\) to \(35.0^oC\) without being allowed to expand? Assume that the bulk modulus \(B\) for gasoline is \(1.00 \times 10^9 \, N/m^2\). (For more on bulk modulus, see Elasticity: Stress and Strain.)

Strategy

To solve this problem, we must use the following equation, which relates a change in volume \(\Delta V\) to pressure:

\[\Delta V = \dfrac{1}{B}\dfrac{F}{A}V_0, \nonumber \]

where \(F/A\) is pressure, \(V_0\) is the original volume, and \(B\) is the bulk modulus of the material involved. We will use the amount spilled in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\) as the change in volume, \(\Delta V\).

Solution

1. Rearrange the equation for calculating pressure: \[P = \dfrac{F}{A} = \dfrac{\Delta V}{V_0}B. \nonumber\]

2. Insert the known values. The bulk modulus for gasoline is \(B = 1.00 \times 10^9 \, N/m^2\). In the previous example, the change in volume \(\Delta V = 1.10 \, L\) is the amount that would spill. Here, \(V_0 = 60.0 \, L\) is the original volume of the gasoline. Substituting these values into the equation, we obtain

\[P = \dfrac{1.10 \, L}{60.0 \, L}(1.00 \times 10^9 Pa) = 1.83 \times 10^7 \, Pa. \nonumber\]

Discussion

This pressure is about \(2500 \, lb/in^2\), much more than a gasoline tank can handle.

Forces and pressures created by thermal stress are typically as great as that in the example above. Railroad tracks and roadways can buckle on hot days if they lack sufficient expansion joints. (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Power lines sag more in the summer than in the winter, and will snap in cold weather if there is insufficient slack. Cracks open and close in plaster walls as a house warms and cools. Glass cooking pans will crack if cooled rapidly or unevenly, because of differential contraction and the stresses it creates. (Pyrex is less susceptible because of its small coefficient of thermal expansion.) Nuclear reactor pressure vessels are threatened by overly rapid cooling, and although none have failed, several have been cooled faster than considered desirable. Biological cells are ruptured when foods are frozen, detracting from their taste. Repeated thawing and freezing accentuate the damage. Even the oceans can be affected. A significant portion of the rise in sea level that is resulting from global warming is due to the thermal expansion of sea water.

Metal is regularly used in the human body for hip and knee implants. Most implants need to be replaced over time because, among other things, metal does not bond with bone. Researchers are trying to find better metal coatings that would allow metal-to-bone bonding. One challenge is to find a coating that has an expansion coefficient similar to that of metal. If the expansion coefficients are too different, the thermal stresses during the manufacturing process lead to cracks at the coating-metal interface.

Another example of thermal stress is found in the mouth. Dental fillings can expand differently from tooth enamel. It can give pain when eating ice cream or having a hot drink. Cracks might occur in the filling. Metal fillings (gold, silver, etc.) are being replaced by composite fillings (porcelain), which have smaller coefficients of expansion, and are closer to those of teeth.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

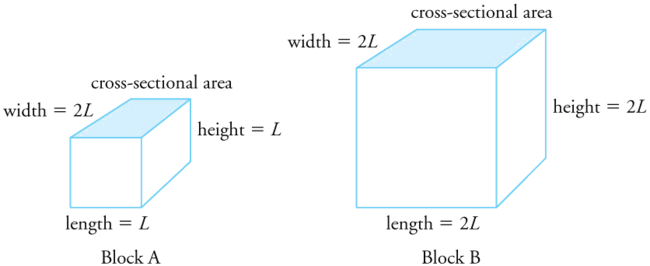

Two blocks, A and B, are made of the same material. Block A has dimensions \(l \times w \times h = L \times 2L \times L\) and Block B has dimensions \(2L \times 2L \times 2L\). If the temperature changes, what is

- the change in the volume of the two blocks,

- the change in the cross-sectional area \(l \times w\) and

- the change in the height \(h\) of the two blocks?

- Answer a

-

The change in volume is proportional to the original volume. Block A has a volume of \(L \times 2L \times L = 2L^3\). Block B has a volume of \(2L \times 2L \times 2L = 8L^3\),

which is 4 times that of Block A. Thus the change in volume of Block B should be 4 times the change in volume of Block A.

- Answer b

-

The change in area is proportional to the area. The cross-sectional area of Block A is \(L \times 2L = 2L^2\), while that of Block B is \(2L \times 2L = 4L^2\).

Because cross-sectional area of Block B is twice that of Block A, the change in the cross-sectional area of Block B is twice that of Block A.

- Answer c

-

The change in height is proportional to the original height. Because the original height of Block B is twice that of A, the change in the height of Block B is twice that of Block A.

Summary

- Thermal expansion is the increase, or decrease, of the size (length, area, or volume) of a body due to a change in temperature.

- Thermal expansion is large for gases, and relatively small, but not negligible, for liquids and solids.

- Linear thermal expansion is \[\Delta L = \alpha L \Delta T, \nonumber\] where \(\Delta L \) is the change in length \(L\), \(\Delta T\) is the change in temperature, and \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of linear expansion, which varies slightly with temperature.

- The change in area due to thermal expansion is \[\Delta A = 2\alpha A \delta T, \nonumber\] where \(\Delta A\) is the change in area.

- The change in volume due to thermal expansion is \[\Delta V = \beta V \delta T, \nonumber\] where \(\beta\) is the coefficient of volume expansion and \(\beta \approx 3\alpha\). Thermal stress is created when thermal expansion is constrained.

Glossary

- thermal expansion

- the change in size or volume of an object with change in temperature

- coefficient of linear expansion

- the change in length, per unit length, per 1 degree Celsius, change in temperature; a constant used in the calculation of linear expansion; the coefficient of linear expansion depends on the material and to some degree on the temperature of the material

- coefficient of volume expansion

- the change in volume, per unit volume, per 1 degree Celsius,change in temperature

- thermal stress

- stress caused by thermal expansion or contraction