13.1: Temperature

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define temperature.

- Convert temperatures between the Celsius, Fahrenheit, and Kelvin scales.

- Define thermal equilibrium.

- State the zeroth law of thermodynamics.

The concept of temperature has evolved from the common concepts of hot and cold. Human perception of what feels hot or cold is a relative one. For example, if you place one hand in hot water and the other in cold water, and then place both hands in tepid water, the tepid water will feel cool to the hand that was in hot water, and warm to the one that was in cold water. The scientific definition of temperature is less ambiguous than your senses of hot and cold. Temperature is operationally defined to be what we measure with a thermometer. (Many physical quantities are defined solely in terms of how they are measured. We shall see later how temperature is related to the kinetic energies of atoms and molecules, a more physical explanation.) Two accurate thermometers, one placed in hot water and the other in cold water, will show the hot water to have a higher temperature. If they are then placed in the tepid water, both will give identical readings (within measurement uncertainties). In this section, we discuss temperature, its measurement by thermometers, and its relationship to thermal equilibrium. Again, temperature is the quantity measured by a thermometer.

Misconception Alert: Human Perception vs. Reality

On a cold winter morning, the wood on a porch feels warmer than the metal of your bike. The wood and bicycle are in thermal equilibrium with the outside air, and are thus the same temperature. They feel different because of the difference in the way that they conduct heat away from your skin. The metal conducts heat away from your body faster than the wood does (see more about conductivity in Conduction). This is just one example demonstrating that the human sense of hot and cold is not determined by temperature alone.

Another factor that affects our perception of temperature is humidity. Most people feel much hotter on hot, humid days than on hot, dry days. This is because on humid days, sweat does not evaporate from the skin as efficiently as it does on dry days. It is the evaporation of sweat (or water from a sprinkler or pool) that cools us off.

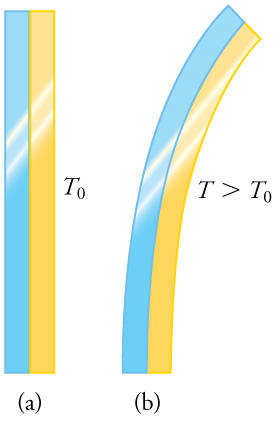

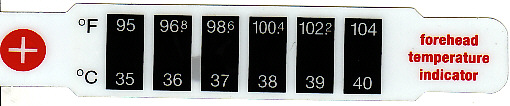

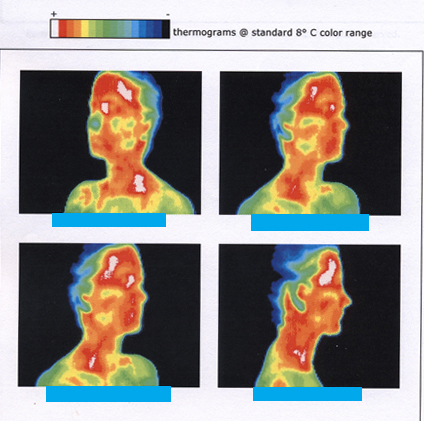

Any physical property that depends on temperature, and whose response to temperature is reproducible, can be used as the basis of a thermometer. Because many physical properties depend on temperature, the variety of thermometers is remarkable. For example, volume increases with temperature for most substances. This property is the basis for the common alcohol thermometer, the old mercury thermometer, and the bimetallic strip (Figure). Other properties used to measure temperature include electrical resistance and color, as shown in Figure, and the emission of infrared radiation, as shown in Figure.

Temperature Scales

Thermometers are used to measure temperature according to well-defined scales of measurement, which use pre-defined reference points to help compare quantities. The three most common temperature scales are the Fahrenheit, Celsius, and Kelvin scales. A temperature scale can be created by identifying two easily reproducible temperatures. The freezing and boiling temperatures of water at standard atmospheric pressure are commonly used.

The Celsius scale (which replaced the slightly different centigrade scale) has the freezing point of water at 0oC and the boiling point at 100oC. Its unit is the degree Celsius (oC). On the Fahrenheit scale (still the most frequently used in the United States), the freezing point of water is at 37oF and the boiling point is at 212oF. The unit of temperature on this scale is the degree Fahrenheit (oF). Note that a temperature difference of one degree Celsius is greater than a temperature difference of one degree Fahrenheit. Only 100 Celsius degrees span the same range as 180 Fahrenheit degrees, thus one degree on the Celsius scale is 1.8 times larger than one degree on the Fahrenheit scale 180/100=9/5.

The Kelvin scale is the temperature scale that is commonly used in science. It is an absolute temperature scale defined to have 0 K at the lowest possible temperature, called absolute zero. The official temperature unit on this scale is the kelvin, which is abbreviated K, and is not accompanied by a degree sign. The freezing and boiling points of water are 273.15 K and 373.15 K, respectively. Thus, the magnitude of temperature differences is the same in units of kelvins and degrees Celsius. Unlike other temperature scales, the Kelvin scale is an absolute scale. It is used extensively in scientific work because a number of physical quantities, such as the volume of an ideal gas, are directly related to absolute temperature. The kelvin is the SI unit used in scientific work.

The relationships between the three common temperature scales is shown in Figure. Temperatures on these scales can be converted using the equations in Table.

| To convert from . . . | Use this equation . . . | Also written as . . . |

|---|---|---|

|

Celsius to Fahrenheit |

T(oF)=95T(Co)+32 |

ToF=95ToC+32 |

|

Fahrenheit to Celsius |

T(oC)=95(T(Fo)−32) |

ToC=59(ToF−32) |

|

Celsius to Kelvin |

T(K)=T(oC)+273.15 |

TK=ToC+273.15 |

|

Kelvin to Celsius |

ToC)=T(K)−273.15 |

ToC=TK−273.15 |

|

Fahrenheit to Kelvin |

T(K)=59(T(oF)−32)+273.15 |

TK=59(ToF−32)+273.15 |

|

Kelvin to Fahrenheit |

T(oF)=95(T(K)−273.15)+32 |

ToF=95(TK−273.15)+32 |

Notice that the conversions between Fahrenheit and Kelvin look quite complicated. In fact, they are simple combinations of the conversions between Fahrenheit and Celsius, and the conversions between Celsius and Kelvin.

Example 13.1.1: Converting between Temperature Scales: Room Temperature

“Room temperature” is generally defined to be 25oC (a) What is room temperature in oF? (b) What is it in K?

Strategy

To answer these questions, all we need to do is choose the correct conversion equations and plug in the known values.

Solution for (a)

1. Choose the right equation. To convert from oC to oF, use this equation

ToF=95ToC+32.

2. Plug the known value into the equation and solve:

ToF=9525oC+32=77oF.

Solution for (b)

1. Choose the right equation. To convert from oC to K, use this equation

TK=ToC+273.15.

2. Plug the known value into the equation and solve:

TK=25oC+273.15=298K.

Example 13.1.2: Plug the known value into the equation and solve:

The Reaumur scale is a temperature scale that was used widely in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. On the Reaumur temperature scale, the freezing point of water is 0oR and the boiling temperature is 80oR. If “room temperature” is 25oC

on the Celsius scale, what is it on the Reaumur scale?

Strategy

To answer this question, we must compare the Reaumur scale to the Celsius scale. The difference between the freezing point and boiling point of water on the Reaumur scale is 80oR. On the Celsius scale it is 100oC. Therefore 100oC=80oR. Both scales start at 0o for freezing, so we can derive a simple formula to convert between temperatures on the two scales.

Solution

1. Derive a formula to convert from one scale to the other:

ToR=0.8oRoC×ToC.

2. Plug the known value into the equation and solve:

ToR=0.8oRoC×25oC=20oR.

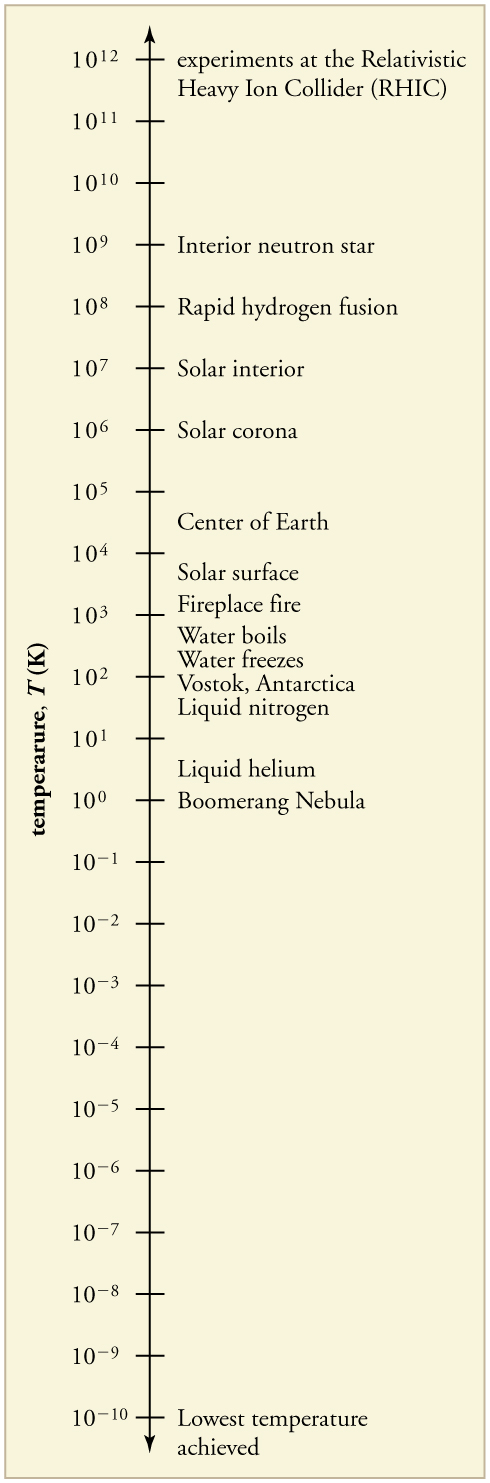

Temperature Ranges in the Universe

Figure shows the wide range of temperatures found in the universe. Human beings have been known to survive with body temperatures within a small range, from 24oC to 44oC(75oF to 111oF). The average normal body temperature is usually given as 37.0oC(98.6oF), and variations in this temperature can indicate a medical condition: a fever, an infection, a tumor, or circulatory problems (see Figure).

The lowest temperatures ever recorded have been measured during laboratory experiments: 4.5×10−10K at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA), and 1.0×10−10K at Helsinki University of Technology (Finland). In comparison, the coldest recorded place on Earth’s surface is Vostok, Antarctica at 183 K (−89oC) and the coldest place (outside the lab) known in the universe is the Boomerang Nebula, with a temperature of 1 K.

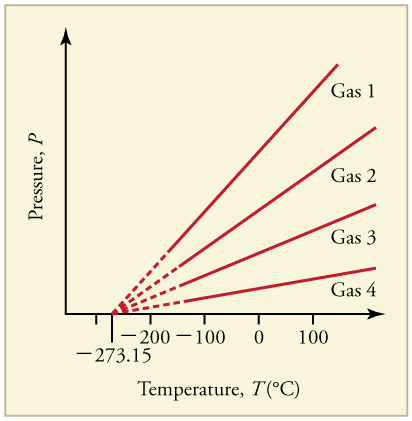

Making Connections: Absolute Zero

What is absolute zero? Absolute zero is the temperature at which all molecular motion has ceased. The concept of absolute zero arises from the behavior of gases. Figure shows how the pressure of gases at a constant volume decreases as temperature decreases. Various scientists have noted that the pressures of gases extrapolate to zero at the same temperature, −273.15oC. This extrapolation implies that there is a lowest temperature. This temperature is called absolute zero. Today we know that most gases first liquefy and then freeze, and it is not actually possible to reach absolute zero. The numerical value of absolute zero temperature is −273.15oC or 0K.

Thermal Equilibrium and the Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

Thermometers actually take their own temperature, not the temperature of the object they are measuring. This raises the question of how we can be certain that a thermometer measures the temperature of the object with which it is in contact. It is based on the fact that any two systems placed in thermal contact (meaning heat transfer can occur between them) will reach the same temperature. That is, heat will flow from the hotter object to the cooler one until they have exactly the same temperature. The objects are then in thermal equilibrium, and no further changes will occur. The systems interact and change because their temperatures differ, and the changes stop once their temperatures are the same. Thus, if enough time is allowed for this transfer of heat to run its course, the temperature a thermometer registers does represent the system with which it is in thermal equilibrium. Thermal equilibrium is established when two bodies are in contact with each other and can freely exchange energy.

Furthermore, experimentation has shown that if two systems, A and B, are in thermal equilibrium with each another, and B is in thermal equilibrium with a third system C, then A is also in thermal equilibrium with C. This conclusion may seem obvious, because all three have the same temperature, but it is basic to thermodynamics. It is called the zeroth law of thermodynamics.

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

If two systems, A and B, are in thermal equilibrium with each other, and B is in thermal equilibrium with a third system, C, then A is also in thermal equilibrium with C.

This law was postulated in the 1930s, after the first and second laws of thermodynamics had been developed and named. It is called the zeroth law because it comes logically before the first and second laws (discussed in Thermodynamics). An example of this law in action is seen in babies in incubators: babies in incubators normally have very few clothes on, so to an observer they look as if they may not be warm enough. However, the temperature of the air, the cot, and the baby is the same, because they are in thermal equilibrium, which is accomplished by maintaining air temperature to keep the baby comfortable.

Check Your Understanding

Does the temperature of a body depend on its size

[Hide Solution]

No, the system can be divided into smaller parts each of which is at the same temperature. We say that the temperature is an intensive quantity. Intensive quantities are independent of size.

Section Summary

- Temperature is the quantity measured by a thermometer.

- Temperature is related to the average kinetic energy of atoms and molecules in a system.

- Absolute zero is the temperature at which there is no molecular motion.

- There are three main temperature scales: Celsius, Fahrenheit, and Kelvin.

- Temperatures on one scale can be converted to temperatures on another scale using the following equations: ToF=95ToC+32 ToC=59ToF−32) TK=ToC+273.15 ToC=TK−273.15

- Systems are in thermal equilibrium when they have the same temperature.

- Thermal equilibrium occurs when two bodies are in contact with each other and can freely exchange energy.

- The zeroth law of thermodynamics states that when two systems, A and B, are in thermal equilibrium with each other, and B is in thermal equilibrium with a third system, C, then A is also in thermal equilibrium with C.

Glossary

- temperature

- the quantity measured by a thermometer

- Celsius scale

- temperature scale in which the freezing point of water is 0ºC and the boiling point of water is 100ºC

- degree Celsius

- unit on the Celsius temperature scale

- Fahrenheit scale

- temperature scale in which the freezing point of water is 32ºF and the boiling point of water is 212ºF

- degree Fahrenheit

- unit on the Fahrenheit temperature scale

- Kelvin scale

- temperature scale in which 0 K is the lowest possible temperature, representing absolute zero

- absolute zero

- the lowest possible temperature; the temperature at which all molecular motion ceases

- thermal equilibrium

- the condition in which heat no longer flows between two objects that are in contact; the two objects have the same temperature

- zeroth law of thermodynamics

- law that states that if two objects are in thermal equilibrium, and a third object is in thermal equilibrium with one of those objects, it is also in thermal equilibrium with the other object