14.5: Conduction

- Page ID

- 1590

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Calculate thermal conductivity.

- Observe conduction of heat in collisions.

- Study thermal conductivities of common substances.

Your feet feel cold as you walk barefoot across the living room carpet in your cold house and then step onto the kitchen tile floor. This result is intriguing, since the carpet and tile floor are both at the same temperature. The different sensation you feel is explained by the different rates of heat transfer: the heat loss during the same time interval is greater for skin in contact with the tiles than with the carpet, so the temperature drop is greater on the tiles.

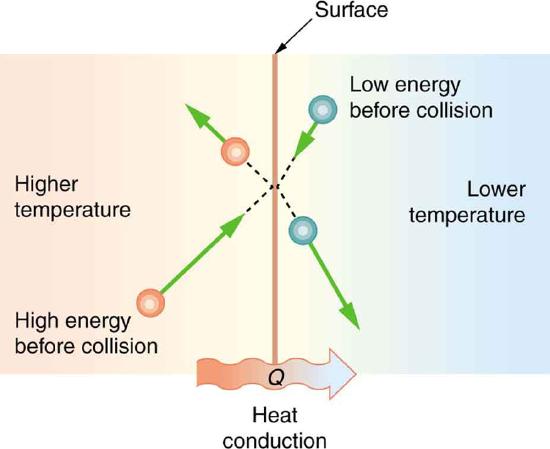

Some materials conduct thermal energy faster than others. In general, good conductors of electricity (metals like copper, aluminum, gold, and silver) are also good heat conductors, whereas insulators of electricity (wood, plastic, and rubber) are poor heat conductors. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows molecules in two bodies at different temperatures. The (average) kinetic energy of a molecule in the hot body is higher than in the colder body. If two molecules collide, an energy transfer from the molecule with greater kinetic energy to the molecule with less kinetic energy occurs. The cumulative effect from all collisions results in a net flux of heat from the hot body to the colder body. The heat flux thus depends on the temperature difference \(\Delta T = T_{hot} - T_{cold}\) Therefore, you will get a more severe burn from boiling water than from hot tap water. Conversely, if the temperatures are the same, the net heat transfer rate falls to zero, and equilibrium is achieved. Owing to the fact that the number of collisions increases with increasing area, heat conduction depends on the cross-sectional area. If you touch a cold wall with your palm, your hand cools faster than if you just touch it with your fingertip.

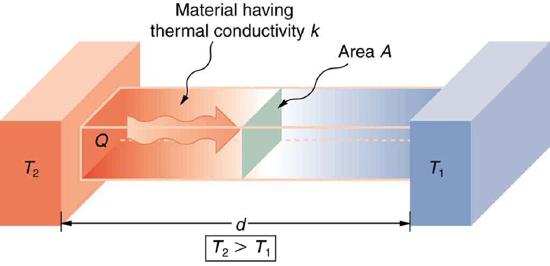

A third factor in the mechanism of conduction is the thickness of the material through which heat transfers. The figure below shows a slab of material with different temperatures on either side. Suppose that \(T_2\) is greater than \(T_1\) so that heat is transferred from left to right. Heat transfer from the left side to the right side is accomplished by a series of molecular collisions. The thicker the material, the more time it takes to transfer the same amount of heat. This model explains why thick clothing is warmer than thin clothing in winters, and why Arctic mammals protect themselves with thick blubber.

Lastly, the heat transfer rate depends on the material properties described by the coefficient of thermal conductivity. All four factors are included in a simple equation that was deduced from and is confirmed by experiments. The rate of conductive heat transfer through a slab of material, such as the one in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), is given by \[\dfrac{Q}{t} = \dfrac{kA(T_2 - T_!)}{d},\] where \(Q/t\) is the rate of heat transfer in watts or kilocalories per second, \(k\) s the thermal conductivity of the material, \(A\) and \(d\) are its surface area and thickness and \((T_2 - T_1)\) is the temperature difference across the slab. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)gives representative values of thermal conductivity.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Heat Transfer Through Conduction: Conduction Rate Through an Ice Box

A Styrofoam ice box has a total area of \(0.950 \, m^2\) and walls with an average thickness of 2.50 cm. The box contains ice, water, and canned beverages at \(0^oC\). The inside of the box is kept cold by melting ice. How much ice melts in one day if the ice box is kept in the trunk of a car at \(35.0^oC\)?

Strategy

This question involves both heat for a phase change (melting of ice) and the transfer of heat by conduction. To find the amount of ice melted, we must find the net heat transferred. This value can be obtained by calculating the rate of heat transfer by conduction and multiplying by time.

Solution

- Identify the knowns. \[A = 0.950 \, m^2; \, d = 2.50 \, cm = 0.0250 \, m; \, T_1 = 35.0^oC, \, t = 1 \, day = 24 \, hours = 86,400 \, sec.\]

- Identify the unknowns. We need to solve for the mass of the ice \(m\). We will also need to solve for the net heat transferred to melt the ice, \(Q\).

- Determine which equations to use. The rate of heat transfer by conduction is given by \[\dfrac{Q}{t} = \dfrac{kA(T_2 - T_1)}{d}.\]

- The heat is used to melt the ice: \(Q = mL_f\).

- Insert the known values: \[\dfrac{Q}{t} = \dfrac{(0.010 \, J/s \cdot m \cdot ^oC)(0.950 \, m^2)(35.0^oC - 0^oC)}{0.0250 \, m} = 13.3 \, J/s.\]

- Multiply the rate of heat transfer by the time \((1 \, day = 86,400 s)\): \[Q = (Q/t)t = (13.3 \, J/s)(86,400 \, s) = 1.15 \times 10^6 \, J.\]

- Set this equal to the heat transferred to melt the ice: \(Q = mL_f\). Solve for the mass \(m\): \[m = \dfrac {Q}{L_f} = \dfrac{1.15 \times 10^6 \, J}{334 \times 10^3 \, J/kg} = 3.44 \, kg.\]

Discussion

The result of 3.44 kg, or about 7.6 lbs, seems about right, based on experience. You might expect to use about a 4 kg (7–10 lb) bag of ice per day. A little extra ice is required if you add any warm food or beverages.

Inspecting the conductivities in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows that Styrofoam is a very poor conductor and thus a good insulator. Other good insulators include fiberglass, wool, and goose-down feathers. Like Styrofoam, these all incorporate many small pockets of air, taking advantage of air’s poor thermal conductivity.

| Substance | Thermal conductivity |

|---|---|

| Air | 0.023 |

| Aluminum | 220 |

| Asbestos | 0.16 |

| Concrete brick | 0.84 |

| Copper | 390 |

| Cork | 0.042 |

| Down feathers | 0.025 |

| Fatty tissue (without blood) | 0.2 |

| Glass (average) | 0.84 |

| Glass wool | 0.042 |

| Gold | 318 |

| Ice | 2.2 |

| Plasterboard | 0.16 |

| Silver | 420 |

| Snow (dry) | 0.10 |

| Steel (stainless) | 14 |

| Steel iron | 80 |

| Styrofoam | 0.010 |

| Water | 0.6 |

| Wood | 0.08–0.16 |

| Wool | 0.04 |

Thermal Conductivities of Common Substances1

A combination of material and thickness is often manipulated to develop good insulators—the smaller the conductivity \(k\) and the larger the thickness \(d\), the better. The ratio of \(d/k\) will thus be large for a good insulator. The ratio \(d/k\) is called the \(R\) factor. The rate of conductive heat transfer is inversely proportional to \(R\). The larger the value of \(R\), the better the insulation. \(R\) factors are most commonly quoted for household insulation, refrigerators, and the like—unfortunately, it is still in non-metric units of \(ft^2 \cdot ^oF \cdot h/Btu\), although the unit usually goes unstated (1 British thermal unit [Btu] is the amount of energy needed to change the temperature of 1.0 lb of water by 1.0 °F). A couple of representative values are an \(R\) factor of 11 for 3.5-in-thick fiberglass batts (pieces) of insulation and an \(R\) factor of 19 for 6.5-in-thick fiberglass batts. Walls are usually insulated with 3.5-in batts, while ceilings are usually insulated with 6.5-in batts. In cold climates, thicker batts may be used in ceilings and walls.

Note that in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), the best thermal conductors—silver, copper, gold, and aluminum—are also the best electrical conductors, again related to the density of free electrons in them. Cooking utensils are typically made from good conductors.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating the Temperature Difference Maintained by a Heat Transfer: Conduction Through an Aluminum Pan

Water is boiling in an aluminum pan placed on an electrical element on a stovetop. The sauce pan has a bottom that is 0.800 cm thick and 14.0 cm in diameter. The boiling water is evaporating at the rate of 1.00 g/s. What is the temperature difference across (through) the bottom of the pan?

Strategy

Conduction through the aluminum is the primary method of heat transfer here, and so we use the equation for the rate of heat transfer and solve for the temperature difference. \[T_2 - T_1 = \dfrac{Q}{t} \left(\dfrac{d}{kA}\right).\]

Solution

- Identify the knowns and convert them to the SI units.

The thickness of the pan, \(d = 0.800 \, cm = 8.0 \times 10^{-3} m\), the area of the pan, \(A = \pi(0.14/2)^2 \, m^2 = 1.54 \times 10^{-2} \, m^2\), and the thermal conductivity, \(k = 220 \, J/s \cdot m \cdot ^oC\).

- Calculate the necessary heat of vaporization of 1 g of water: \[Q = mL_v = (1.00 \times 10^{-3} \, kg)(2256 \times 10^3 \, J/kg) = 2256 \, J.\]

- Calculate the rate of heat transfer given that 1 g of water melts in one second: \[ Q/t = 2256 \, J/s \, or 2.26 kW.\]

- Insert the knowns into the equation and solve for the temperature difference: \[T_2 - T_1 = \dfrac{Q}{t}\left(\dfrac{d}{kA} \right) = (2256 \, J/s) \dfrac{8.00 \times 10^{-3} m}{(220 \, J/s \cdot m \cdot ^oC)(1.54 \times 10^{-2} \, m^2)} = 5.33 ^oC.\]

Discussion

The value for the heat transfer \(Q/t = 2.26 \, kW \, or 2256 \, J/s\) is typical for an electric stove. This value gives a remarkably small temperature difference between the stove and the pan. Consider that the stove burner is red hot while the inside of the pan is nearly \(100^oC\) because of its contact with boiling water. This contact effectively cools the bottom of the pan in spite of its proximity to the very hot stove burner. Aluminum is such a good conductor that it only takes this small temperature difference to produce a heat transfer of 2.26 kW into the pan.

Conduction is caused by the random motion of atoms and molecules. As such, it is an ineffective mechanism for heat transport over macroscopic distances and short time distances. Take, for example, the temperature on the Earth, which would be unbearably cold during the night and extremely hot during the day if heat transport in the atmosphere was to be only through conduction. In another example, car engines would overheat unless there was a more efficient way to remove excess heat from the pistons.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\): Check your understanding

How does the rate of heat transfer by conduction change when all spatial dimensions are doubled?

- Answer

-

Because area is the product of two spatial dimensions, it increases by a factor of four when each dimension is doubled \((A_{final} = (2d)^2 = 4d^2 = 4A_{initial})\). The distance, however, simply doubles. Because the temperature difference and the coefficient of thermal conductivity are independent of the spatial dimensions, the rate of heat transfer by conduction increases by a factor of four divided by two, or two: \[\left(\dfrac{Q}{t} \right)_{final} = \dfrac{kA_{final}(T_2 - T_1)}{d_{final}} = \dfrac{k(4A_{initial})(T_2 - T_1)}{2d_{initial}} = 2 \dfrac{kA_{initial}(T_2 - T_1)}{d_{initial}} = 2\left(\dfrac{Q}{t}\right)_{initial}\]

Summary

Heat conduction is the transfer of heat between two objects in direct contact with each other. The rate of heat transfer \(Q/t\) (energy per unit time) is proportional to the temperature difference \(T_2 - T_1\) and the contact area \(A\) and inversely proportional to the distance between the objects: \[\dfrac{Q}{t} = \dfrac{kA(T_2 - T_1)}{d}.\]

Footnotes

- At temperatures near 0ºC.

Glossary

- R factor

- the ratio of thickness to the conductivity of a material

- rate of conductive heat transfer

- rate of heat transfer from one material to another

- thermal conductivity

- the property of a material’s ability to conduct heat