16.9: Waves

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the characteristics of a wave.

- Calculate the velocity of wave propagation.

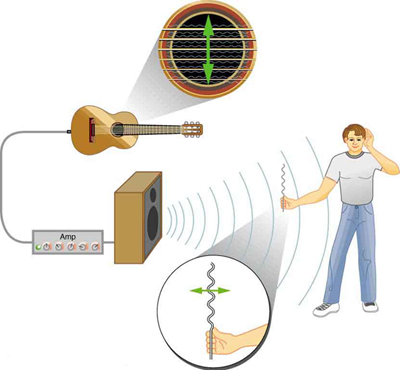

What do we mean when we say something is a wave? The most intuitive and easiest wave to imagine is the familiar water wave. More precisely, a wave is a disturbance that propagates, or moves from the place it was created. For water waves, the disturbance is in the surface of the water, perhaps created by a rock thrown into a pond or by a swimmer splashing the surface repeatedly. For sound waves, the disturbance is a change in air pressure, perhaps created by the oscillating cone inside a speaker. For earthquakes, there are several types of disturbances, including disturbance of Earth’s surface and pressure disturbances under the surface. Even radio waves are most easily understood using an analogy with water waves. Visualizing water waves is useful because there is more to it than just a mental image. Water waves exhibit characteristics common to all waves, such as amplitude, period, frequency and energy. All wave characteristics can be described by a small set of underlying principles.

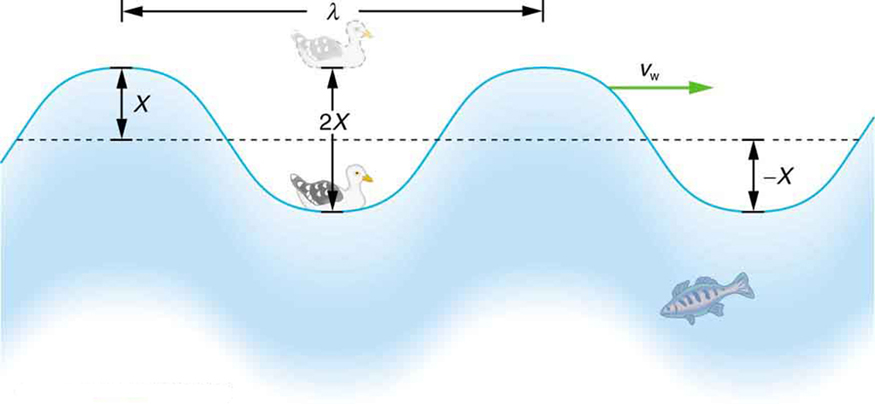

A wave is a disturbance that propagates, or moves from the place it was created. The simplest waves repeat themselves for several cycles and are associated with simple harmonic motion. Let us start by considering the simplified water wave in Figure 16.9.2. The wave is an up and down disturbance of the water surface. It causes a sea gull to move up and down in simple harmonic motion as the wave crests and troughs (peaks and valleys) pass under the bird. The time for one complete up and down motion is the wave’s period T. The wave’s frequency is f=1/T, as usual. The wave itself moves to the right in the figure. This movement of the wave is actually the disturbance moving to the right, not the water itself (or the bird would move to the right). We define wave velocity vw to be the speed at which the disturbance moves. Wave velocity is sometimes also called the propagation velocity or propagation speed, because the disturbance propagates from one location to another.

MISCONCEPTION ALERT

Many people think that water waves push water from one direction to another. In fact, the particles of water tend to stay in one location, save for moving up and down due to the energy in the wave. The energy moves forward through the water, but the water stays in one place. If you feel yourself pushed in an ocean, what you feel is the energy of the wave, not a rush of water.

The water wave in Figure 16.9.2 also has a length associated with it, called its wavelength λ the distance between adjacent identical parts of a wave. (λ is the distance parallel to the direction of propagation.) The speed of propagation vw is the distance the wave travels in a given time, which is one wavelength in the time of one period. In equation form, that is

vw=λT

or

vw=fλ.

This fundamental relationship holds for all types of waves. For water waves, vw is the speed of a surface wave; for sound, vw is the speed of sound; and for visible light, vw is the speed of light, for example.

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: WAVES IN A BOWL

Fill a large bowl or basin with water and wait for the water to settle so there are no ripples. Gently drop a cork into the middle of the bowl. Estimate the wavelength and period of oscillation of the water wave that propagates away from the cork. Remove the cork from the bowl and wait for the water to settle again. Gently drop the cork at a height that is different from the first drop. Does the wavelength depend upon how high above the water the cork is dropped?

Example 16.9.1: Calculate the Velocity of Wave Propagation: Gull in the Ocean

Calculate the wave velocity of the ocean wave in Figure 16.9.2 if the distance between wave crests is 10.0 m and the time for a sea gull to bob up and down is 5.00 s.

Strategy

We are asked to find vw. The given information tells us that λ=10.0m and T=5.00s. Therefore, we can use Equation ??? to find the wave velocity.

Solution

- Enter the known values into Equation ???: vw=λT=10.0m5.00s.

- Solve for vw to find vw=2.00m/s.

Discussion

This slow speed seems reasonable for an ocean wave. Note that the wave moves to the right in the figure at this speed, not the varying speed at which the sea gull moves up and down.

Transverse and Longitudinal Waves

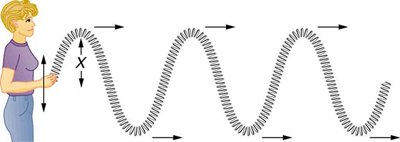

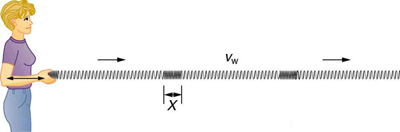

A simple wave consists of a periodic disturbance that propagates from one place to another. The wave in Figure 16.9.3 propagates in the horizontal direction while the surface is disturbed in the vertical direction. Such a wave is called a transverse wave or shear wave; in such a wave, the disturbance is perpendicular to the direction of propagation. In contrast, in a longitudinal wave or compressional wave, the disturbance is parallel to the direction of propagation. Figure 16.9.4 shows an example of a longitudinal wave. The size of the disturbance is its amplitude X and is completely independent of the speed of propagation vw.

Waves may be transverse, longitudinal, or a combination of the two. (Water waves are actually a combination of transverse and longitudinal. The simplified water wave illustrated in Figure 16.9.2shows no longitudinal motion of the bird.) The waves on the strings of musical instruments are transverse—so are electromagnetic waves, such as visible light.

Sound waves in air and water are longitudinal. Their disturbances are periodic variations in pressure that are transmitted in fluids. Fluids do not have appreciable shear strength, and thus the sound waves in them must be longitudinal or compressional. Sound in solids can be both longitudinal and transverse.

Earthquake waves under Earth’s surface also have both longitudinal and transverse components (called compressional or P-waves and shear or S-waves, respectively). These components have important individual characteristics—they propagate at different speeds, for example. Earthquakes also have surface waves that are similar to surface waves on water.

Exercise 16.9.1:Check Your Understanding

Why is it important to differentiate between longitudinal and transverse waves?

- Answer

-

In the different types of waves, energy can propagate in a different direction relative to the motion of the wave. This is important to understand how different types of waves affect the materials around them.

PHET EXPLORATIONS: WAVE ON A STRING

Watch a string vibrate in slow motion with this PhET simulation. Wiggle the end of the string and make waves, or adjust the frequency and amplitude of an oscillator. Adjust the damping and tension. The end can be fixed, loose, or open.

Summary

- A wave is a disturbance that moves from the point of creation with a wave velocity vw.

- A wave has a wavelength λ which is the distance between adjacent identical parts of the wave.

- Wave velocity and wavelength are related to the wave’s frequency and period by vw=λT or vw=fλ.

- A transverse wave has a disturbance perpendicular to its direction of propagation, whereas a longitudinal wave has a disturbance parallel to its direction of propagation.

Glossary

- longitudinal wave

- a wave in which the disturbance is parallel to the direction of propagation

- transverse wave

- a wave in which the disturbance is perpendicular to the direction of propagation

- wave velocity

- the speed at which the disturbance moves. Also called the propagation velocity or propagation speed

- wavelength

- the distance between adjacent identical parts of a wave