21.4: DC Voltmeters and Ammeters

- Page ID

- 2691

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why a voltmeter must be connected in parallel with the circuit.

- Draw a diagram showing an ammeter correctly connected in a circuit.

- Describe how a galvanometer can be used as either a voltmeter or an ammeter.

- Find the resistance that must be placed in series with a galvanometer to allow it to be used as a voltmeter with a given reading.

- Explain why measuring the voltage or current in a circuit can never be exact.

Voltmeters measure voltage, whereas ammeters measure current. Some of the meters in automobile dashboards, digital cameras, cell phones, and tuner-amplifiers are voltmeters or ammeters. (See Figure.) The internal construction of the simplest of these meters and how they are connected to the system they monitor give further insight into applications of series and parallel connections.

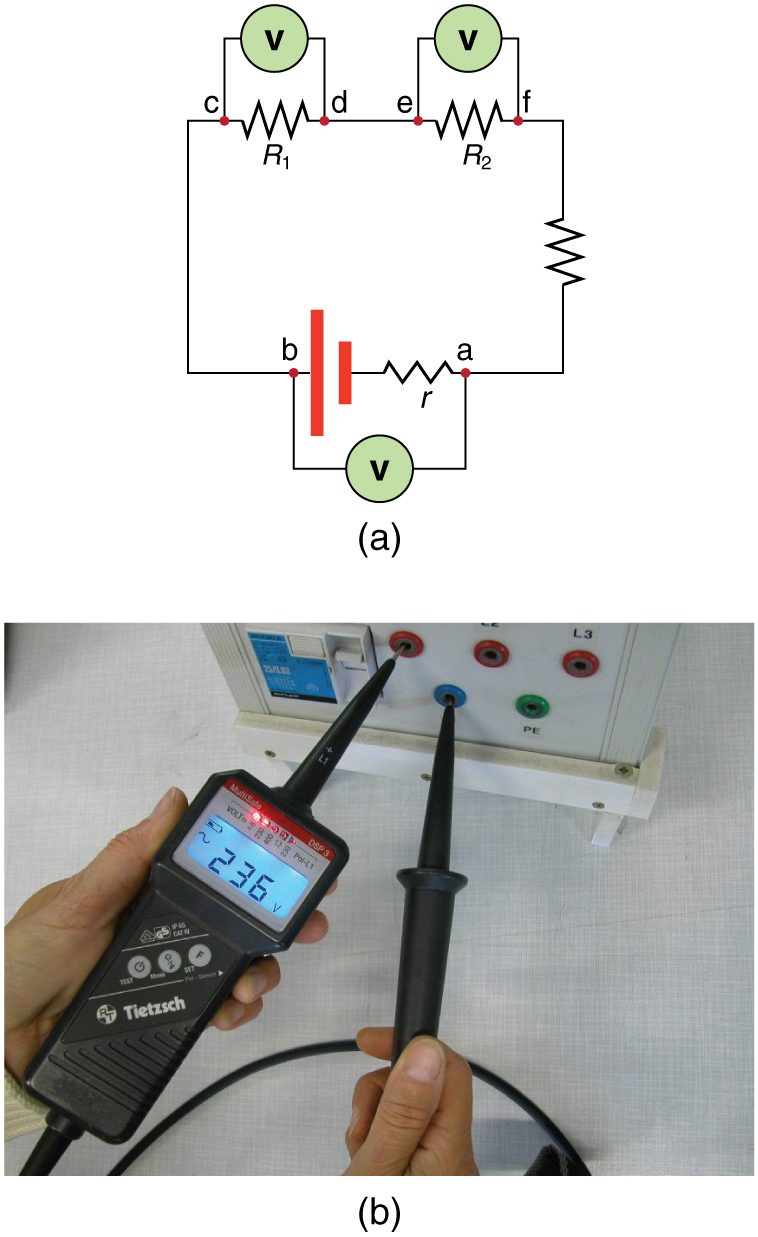

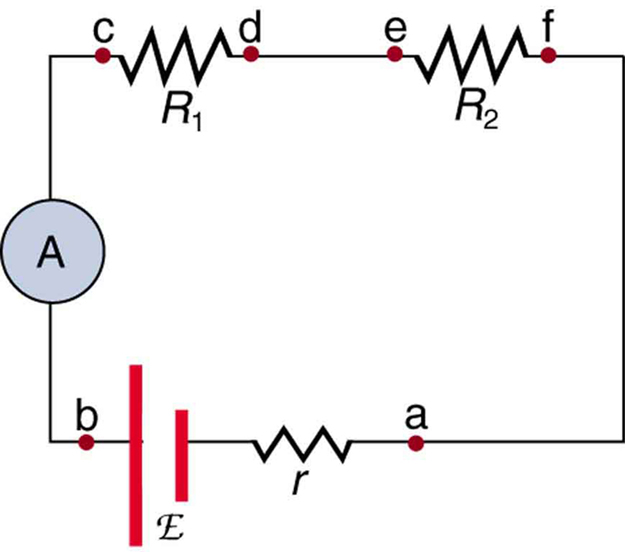

Voltmeters are connected in parallel with whatever device’s voltage is to be measured. A parallel connection is used because objects in parallel experience the same potential difference. (See Figure, where the voltmeter is represented by the symbol V.)

Ammeters are connected in series with whatever device’s current is to be measured. A series connection is used because objects in series have the same current passing through them. (See Figure, where the ammeter is represented by the symbol A.)

Analog Meters: Galvanometers

Analog meters have a needle that swivels to point at numbers on a scale, as opposed to digital meters, which have numerical readouts similar to a hand-held calculator. The heart of most analog meters is a device called a galvanometer, denoted by G. Current flow through a galvanometer, \(I_G\), produces a proportional needle deflection. (This deflection is due to the force of a magnetic field upon a current-carrying wire.)

The two crucial characteristics of a given galvanometer are its resistance and current sensitivity. Current sensitivity is the current that gives a full-scale deflection of the galvanometer’s needle, the maximum current that the instrument can measure. For example, a galvanometer with a current sensitivity of \(50 \mu A\) has a maximum deflection of its needle when \(50 \, \mu A\) flows through it, reads half-scale when \(25 \, \mu A\) flows through it, and so on.

If such a galvanometer has a \(25 \, \Omega\) resistance, then a voltage of only \(V = IR = (50 \, \mu A)(25 \, \Omega) = 1.25 \, mV\) produces a full-scale reading. By connecting resistors to this galvanometer in different ways, you can use it as either a voltmeter or ammeter that can measure a broad range of voltages or currents.

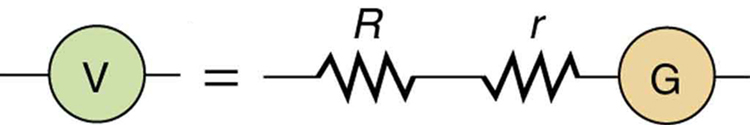

Galvanometer as Voltmeter

Figure shows how a galvanometer can be used as a voltmeter by connecting it in series with a large resistance, \(R\). The value of the resistance \(R\) is determined by the maximum voltage to be measured. Suppose you want 10 V to produce a full-scale deflection of a voltmeter containing a \(25 \, \Omega\) galvanometer with a \(50-\mu A\) sensitivity. Then 10 V applied to the meter must produce a current of \(50 \, \mu A\). The total resistance must be \[R_{tot} = R + r = \dfrac{V}{I} = \dfrac{10 \, V}{50 \, \mu A} = 200 \, k\Omega, \, or\]\[R = T_{tot} - r = 200 \, k\Omega - 25 \, \Omega \approx 200 \, k\Omega.\]

(\(R\) is so large that the galvanometer resistance, \(r\), is nearly negligible.) Note that 5 V applied to this voltmeter produces a half-scale deflection by producing a \(25 \, \mu A\) current through the meter, and so the voltmeter’s reading is proportional to voltage as desired.

This voltmeter would not be useful for voltages less than about half a volt, because the meter deflection would be small and difficult to read accurately. For other voltage ranges, other resistances are placed in series with the galvanometer. Many meters have a choice of scales. That choice involves switching an appropriate resistance into series with the galvanometer.

Galvanometer as Ammeter

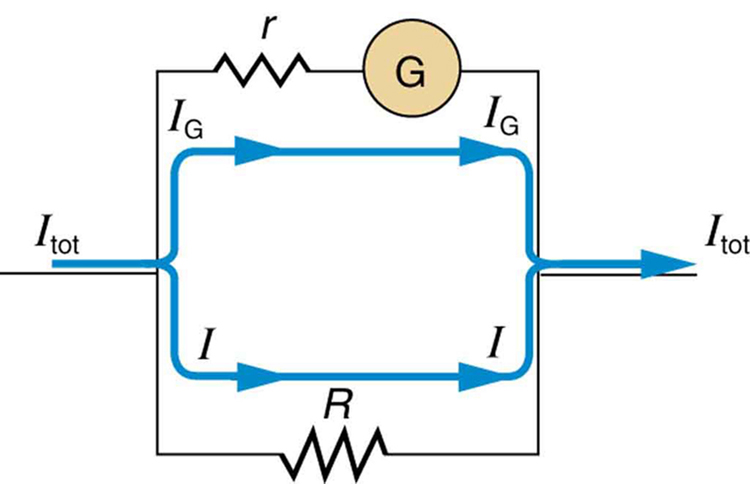

The same galvanometer can also be made into an ammeter by placing it in parallel with a small resistance \(R\), often called the shunt resistance, as shown in Figure. Since the shunt resistance is small, most of the current passes through it, allowing an ammeter to measure currents much greater than those producing a full-scale deflection of the galvanometer.

Suppose, for example, an ammeter is needed that gives a full-scale deflection for 1.0 A, and contains the same \(25-\Omega\) galvanometer with its \(50-\mu A\) sensitivity. Since \(R\) and \(r\) are in parallel, the voltage across them is the same.

These \(IR\) drops are \(IR = I_Cr\) so that \(IR = \frac{I_G}{I} = \frac{R}{r}\). Solving for \(R\), and noting that \(I_G\) is \(50 \, \mu A\) and \(I\) is 0.999950 A, we have \[R = r\dfrac{I_G}{I} = (25 \, \Omega) \dfrac{50 \, \mu A}{0.999950 \, A} = 1.25 \times 10^{-3} \, \Omega.\]

Taking Measurements Alters the Circuit

When you use a voltmeter or ammeter, you are connecting another resistor to an existing circuit and, thus, altering the circuit. Ideally, voltmeters and ammeters do not appreciably affect the circuit, but it is instructive to examine the circumstances under which they do or do not interfere.

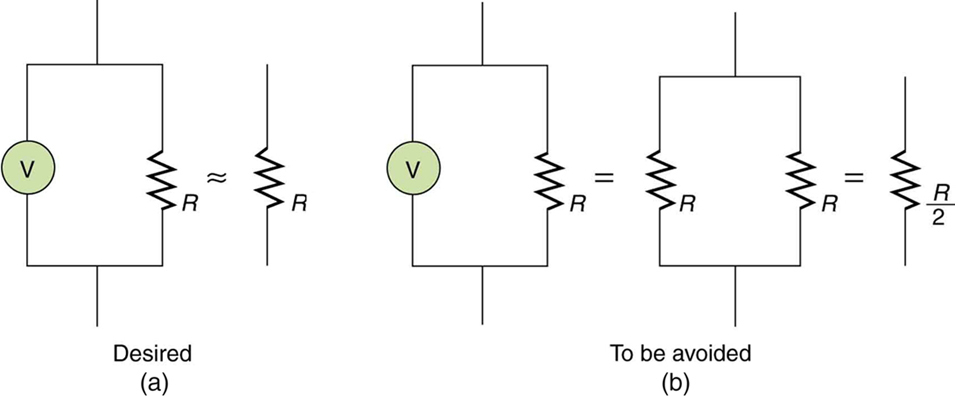

First, consider the voltmeter, which is always placed in parallel with the device being measured. Very little current flows through the voltmeter if its resistance is a few orders of magnitude greater than the device, and so the circuit is not appreciably affected. (See Figure(a).) (A large resistance in parallel with a small one has a combined resistance essentially equal to the small one.) If, however, the voltmeter’s resistance is comparable to that of the device being measured, then the two in parallel have a smaller resistance, appreciably affecting the circuit. (See Figure(b).) The voltage across the device is not the same as when the voltmeter is out of the circuit.

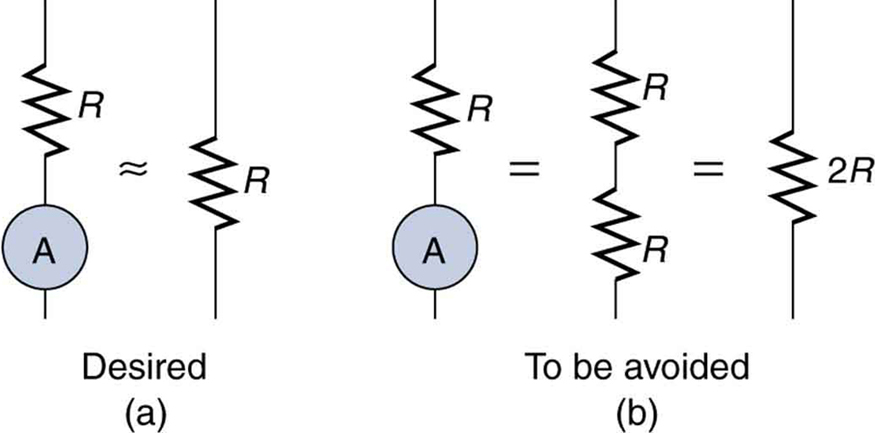

An ammeter is placed in series in the branch of the circuit being measured, so that its resistance adds to that branch. Normally, the ammeter’s resistance is very small compared with the resistances of the devices in the circuit, and so the extra resistance is negligible. (See Figure(a).) However, if very small load resistances are involved, or if the ammeter is not as low in resistance as it should be, then the total series resistance is significantly greater, and the current in the branch being measured is reduced. (See Figure(b).)

A practical problem can occur if the ammeter is connected incorrectly. If it was put in parallel with the resistor to measure the current in it, you could possibly damage the meter; the low resistance of the ammeter would allow most of the current in the circuit to go through the galvanometer, and this current would be larger since the effective resistance is smaller.

One solution to the problem of voltmeters and ammeters interfering with the circuits being measured is to use galvanometers with greater sensitivity. This allows construction of voltmeters with greater resistance and ammeters with smaller resistance than when less sensitive galvanometers are used.

There are practical limits to galvanometer sensitivity, but it is possible to get analog meters that make measurements accurate to a few percent. Note that the inaccuracy comes from altering the circuit, not from a fault in the meter.

CONNECTIONS: LIMITS TO KNOWLEDGE

Making a measurement alters the system being measured in a manner that produces uncertainty in the measurement. For macroscopic systems, such as the circuits discussed in this module, the alteration can usually be made negligibly small, but it cannot be eliminated entirely. For submicroscopic systems, such as atoms, nuclei, and smaller particles, measurement alters the system in a manner that cannot be made arbitrarily small. This actually limits knowledge of the system—even limiting what nature can know about itself. We shall see profound implications of this when the Heisenberg uncertainty principle is discussed in the modules on quantum mechanics.

There is another measurement technique based on drawing no current at all and, hence, not altering the circuit at all. These are called null measurements and are the topic of Null Measurements. Digital meters that employ solid-state electronics and null measurements can attain accuracies of one part in \(10^6\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Digital meters are able to detect smaller currents than analog meters employing galvanometers. How does this explain their ability to measure voltage and current more accurately than analog meters?

- Answer

-

Since digital meters require less current than analog meters, they alter the circuit less than analog meters. Their resistance as a voltmeter can be far greater than an analog meter, and their resistance as an ammeter can be far less than an analog meter. Consult Figure and Figure and their discussion in the text.

PHET EXPLORATIONS: CIRCUIT CONSTRUCTION KIT (DC ONLY), VIRTUAL LAB

Stimulate a neuron and monitor what happens. Pause, rewind, and move forward in time in order to observe the ions as they move across the neuron membrane.

Summary

- Voltmeters measure voltage, and ammeters measure current.

- A voltmeter is placed in parallel with the voltage source to receive full voltage and must have a large resistance to limit its effect on the circuit.

- An ammeter is placed in series to get the full current flowing through a branch and must have a small resistance to limit its effect on the circuit.

- Both can be based on the combination of a resistor and a galvanometer, a device that gives an analog reading of current.

- Standard voltmeters and ammeters alter the circuit being measured and are thus limited in accuracy.

Glossary

- voltmeter

- an instrument that measures voltage

- ammeter

- an instrument that measures current

- analog meter

- a measuring instrument that gives a readout in the form of a needle movement over a marked gauge

- digital meter

- a measuring instrument that gives a readout in a digital form

- galvanometer

- an analog measuring device, denoted by G, that measures current flow using a needle deflection caused by a magnetic field force acting upon a current-carrying wire

- current sensitivity

- the maximum current that a galvanometer can read

- full-scale deflection

- the maximum deflection of a galvanometer needle, also known as current sensitivity; a galvanometer with a full-scale deflection of \(50 \, \mu A\) has a maximum deflection of its needle when \(50 \, \mu A\) flows through it

- shunt resistance

- a small resistance \(R\) placed in parallel with a galvanometer G to produce an ammeter; the larger the current to be measured, the smaller \(R\) must be; most of the current flowing through the meter is shunted through \(R\) to protect the galvanometer