3.5: The Gaussian Integral

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Here’s a famous integral: ∫∞−∞e−γx2dx.

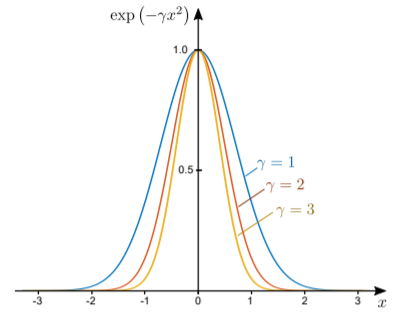

The integrand is called a Gaussian, or bell curve, and is plotted below. The larger the value of γ, the more narrowly-peaked the curve.

The integral was solved by Gauss in a brilliant way. Let I(γ) denote the value of the integral. Then I2 is just two independent copies of the integral, multiplied together: I2(γ)=[∫∞−∞dxe−γx2]×[∫∞−∞dye−γy2].

Note that in the second copy of the integral, we have changed the “dummy” label x (the integration variable) into y, to avoid ambiguity. Now, this becomes a two-dimensional integral, taken over the entire 2D plane: I2(γ)=∫∞−∞dx∫∞−∞dye−γ(x2+y2).

Next, change from Cartesian to polar coordinates: I2(γ)=∫∞0drr∫2π0dϕe−γr2=[∫∞0drre−γr2]×[∫2π0dϕ]=12γ⋅2π.

By taking the square root, we arrive at the result I(γ)=∫∞−∞dxe−γx2=√πγ.