2.2: Plane-Waves

- Page ID

- 15730

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)As we have just seen, a wave of amplitude \(A\), wavenumber \(k\), angular frequency \(\omega\), and phase angle \(\varphi\), propagating in the positive \(x\)-direction, is represented by the following wavefunction:

\[\label{e10.1} \psi(x,t)=A\,\cos(k\,x-\omega\,t+\varphi).\] This type of wave is conventionally termed a one-dimensional plane-wave. It is one-dimensional because its associated wavefunction only depends on the single Cartesian coordinate, \(x\). Furthermore, it is a plane-wave because the wave maxima, which are located at

\[\label{e10.2} k\,x-\omega\,t+\varphi = j\,2\pi,\] where \(j\) is an integer, consist of a series of parallel planes, normal to the \(x\)-axis, that are equally spaced a distance \(\lambda=2\pi/k\) apart, and propagate along the positive \(x\)-axis at the velocity \(v=\omega/k\). These conclusions follow because Equation (2.2.2) can be rewritten in the form

\[\label{e10.3} x= d,\] where \(d=(j-\varphi/2\pi)\,\lambda + v\,t\). Moreover, as is well known, Equation (2.2.3) is the equation of a plane, normal to the \(x\)-axis, whose distance of closest approach to the origin is \(d\).

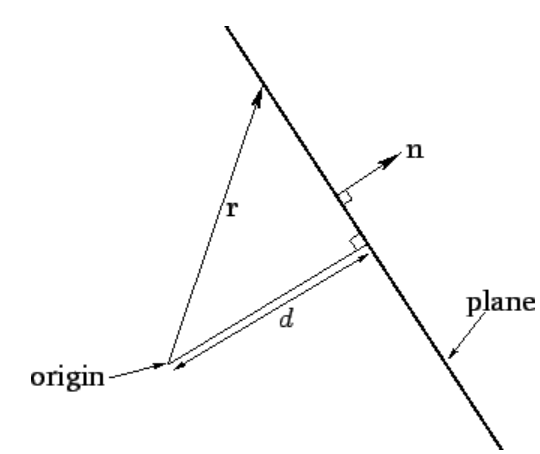

Figure 1: The solution of \(\begin{equation}\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{r}=d\end{equation}\) is a plane.

The previous equation can also be written in the coordinate-free form

\[\label{e10.4} {\bf n}\cdot{\bf r} = d,\] where \({\bf n} = (1,\,0,\,0)\) is a unit vector directed along the positive \(x\)-axis, and \({\bf r}=(x,\,y,\,z)\) represents the vector displacement of a general point from the origin. Because there is nothing special about the \(x\)-direction, it follows that if \({\bf n}\) is reinterpreted as a unit vector pointing in an arbitrary direction then Equation (2.2.4) can be reinterpreted as the general equation of a plane. As before, the plane is normal to \({\bf n}\), and its distance of closest approach to the origin is \(d\). See Figure [f10.1]. This observation allows us to write the three-dimensional equivalent to the wavefunction (2.2.1) as

\[\label{e10.5} \psi({\bf r},t)=A\,\cos({\bf k}\cdot{\bf r}-\omega\,t+\varphi),\]

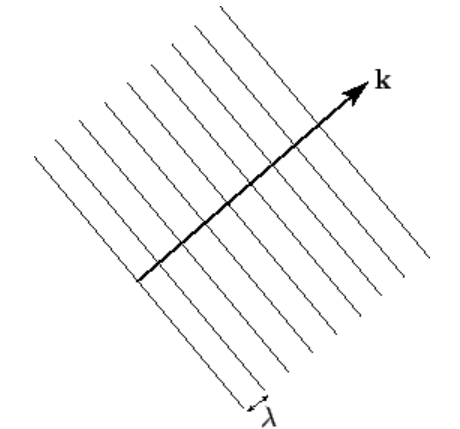

where the constant vector \({\bf k} = (k_x,\,k_y,\,k_z)=k\,{\bf n}\) is called the wavevector. The wave represented previously is conventionally termed a three-dimensional plane-wave. It is three-dimensional because its wavefunction, \(\psi({\bf r},t)\), depends on all three Cartesian coordinates. Moreover, it is a plane-wave because the wave maxima are located at \[{\bf k}\cdot{\bf r} -\omega\,t +\varphi= j\,2\pi,\] or \[{\bf n}\cdot{\bf r} = (j-\varphi/2\pi)\,\lambda + v\,t,\] where \(\lambda=2\pi/k\), and \(v=\omega/k\). Note that the wavenumber, \(k\), is the magnitude of the wavevector, \({\bf k}\): that is, \(k\equiv |{\bf k}|\). It follows, by comparison with Equation (2.2.4), that the wave maxima consist of a series of parallel planes, normal to the wavevector, that are equally spaced a distance \(\lambda\) apart, and that propagate in the \({\bf k}\)-direction at the velocity \(v\). See Figure [f10.2]. Hence, the direction of the wavevector specifies the wave propagation direction, whereas its magnitude determines the wavenumber, \(k\), and, thus, the wavelength, \(\lambda=2\pi/k\).

Figure 2: Wave maxima associated with a three-dimensional plane wave.

Contributors and Attributions

Richard Fitzpatrick (Professor of Physics, The University of Texas at Austin)

\( \newcommand {\ltapp} {\stackrel {_{\normalsize<}}{_{\normalsize \sim}}}\) \(\newcommand {\gtapp} {\stackrel {_{\normalsize>}}{_{\normalsize \sim}}}\) \(\newcommand {\btau}{\mbox{\boldmath$\tau$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bmu}{\mbox{\boldmath$\mu$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bsigma}{\mbox{\boldmath$\sigma$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bOmega}{\mbox{\boldmath$\Omega$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bomega}{\mbox{\boldmath$\omega$}}\) \(\newcommand {\bepsilon}{\mbox{\boldmath$\epsilon$}}\)