12.8: The Thermodynamic Functions for Other Substances

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Calculation of the change in the thermodynamic functions of any substance going reversibly from PlV1T1 to P2V2T2.

The first comforting thing to note is that SUHAG are all state functions, and therefore the change in their values is route-independent.

Entropy.

Entropy is a function of state (i.e. of PVT), but since PVT are related through the equation of state, it is necessary to specify only two of these quantities. Thus, for example if we express S as a function of T and P, infinitesimal increases in these will give rise to an infinitesimal increase in S given by

dS=(∂S∂T)PdT+(∂S∂P)TdP

Now (∂S∂T)P is (for a reversible process) CPT (see equation 12.7.5), and (∂S∂P)T is (by a Maxwell relation) equal to −(∂V∂T)P. If we know CP as a function of temperature, and, if we know the equation of state, we can now calculate

S2−S1=∫T2T1CPdTT−∫P2P1(∂V∂T)PdP

This will enable us to calculate the change in entropy of a substance provided that we know how the heat capacity varies with temperature and provided that we know the equation of state.

For an ideal gas (∂V∂T)P=R/P, and so we obtain, for an ideal gas

S2−S1=∫T2T1CPdTT−Rln(P2/P1).

If we want to express the increase of entropy in terms of the change in temperature and volume, and of CV, we can use PV = RT and CP = CV + R to obtain

S2−S1=∫T2T1CVdTT+Rln(V2/V1)

This agrees with what we had in the previous section for an isothermal expansion.

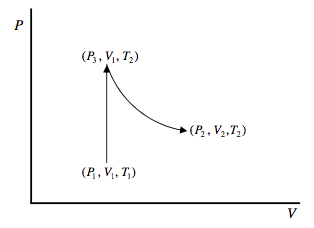

Here’s another way or arriving at equation 12.9.4. We want to find the change in entropy of a mole of an ideal gas in going from (P1, V1, T1) to (P2, V2, T2). Since the change in entropy is route-independent, we can choose any simple route for which the calculation is easy. Let’s go at constant volume from (P1, V1, T1) to (P3, V1, T2) and then at constant temperature from (P3, V1, T2) to (P2, V2, T2).

To go from (P1, V1, T1) to (P3, V1, T2), the gas has to absorb an amount of heat ∫T2T1CVdT, and so its entropy increases by ∫T2T1CVdTT. To go from (P3, V1, T2) to (P2, V2, T2). The gas does work RT2 ln(V2/V1) without any change in internal energy (because the internal energy of an ideal gas at constant temperature is independent of its volume), and therefore it absorbs this amount of heat. Therefore its entropy increases by R ln(V2/V1). Thus we arrive again at equation 12.9.4.

Example: If the substance is an ideal monatomic gas, then CP=52R. From this we calculate

S2−S1=52Rln(T2T1)−Rln(P2P1)=Rln[(T2T1)5/2P1P2].

Exercise: Go through the same analysis, but starting from S = S(T, V). Show that the result you get for an ideal gas is the same as above. It will also, of course, necessarily be the same for any substance, though the equality of the expression you get with equation 12.9.2 may not be immediately apparent.

Exercise: The pressure and volume of an ideal monatomic gas are both doubled. What is the ratio of the new temperature to the old? What is the increase in the molar entropy?

(I make the answer 2.31 × 104 J kmole−1 K−1.) Now try the same problem with an ideal diatomic gas. (I make the answer 3.46 × 104 J kmole−1 K−1.)

Internal Energy and Enthalpy

These can be calculated if we know how CV and CP vary with temperature, because, by definition, CV = (∂U/∂T)V and CP = (∂H/∂T)P.

Therefore

U2−U1=∫T2T1CVdT

and

H2−H1=∫T2T1CPdT.

Helmholtz and Gibbs Functions

Since A = U − TS, we have

A2−A1=U2−U1−T2(S2−S1)−S1(T2−T1).

In the special case of an ideal gas, we obtain

A2−A1=∫T2T1CVdT−T2∫T2T1CVdTT−RT2ln(V2/V1)−S1(T2−T1).

Since G = H − TS, we have

G2−G1=H2−H1−T2(S2−S1)−S1(T2−T1)

In the special case of an ideal gas, we obtain

G2−G1=∫T2T1CpdT−T2∫T2T1CPdTT−RT2ln(P1/P2)−S1(T2−T1).

There is, however, a serious difficulty with equations 12.9.9 and 12.9.11, in that, in order to calculate the change in the Helmholtz and Gibbs functions, we need to know the initial absolute entropy S1.