4.1: Galilean Spacetime Thinking

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

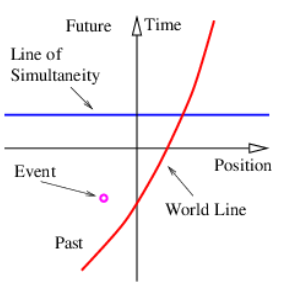

In order to gain an understanding of both Galilean and Einsteinian relativity it is important to begin thinking of space and time as being different dimensions of a four-dimensional space called spacetime. Actually, since we can’t visualize four dimensions very well, it is easiest to start with only one space dimension and the time dimension. Figure 4.1.1: shows a graph with time plotted on the vertical axis and the one space dimension plotted on the horizontal axis. An event is something that occurs at a particular time and a particular point in space. (“Julius X. wrecks his car in Lemitar, NM on 21 June at 6:17 PM.”) A world line is a plot of the position of some object as a function of time on a spacetime diagram, although it is conventional to put time on the vertical axis. Thus, a world line is really a line in space time, while an event is a point in space time. A horizontal line parallel to the position axis is a line of simultaneity in Galilean relativity — i. e., all events on this line occur simultaneously.

In a spacetime diagram the slope of a world line has a special meaning. Notice that a vertical world line means that the object it represents does not move — the velocity is zero. If the object moves to the right, then the world line tilts to the right, and the faster it moves, the more the world line tilts. Quantitatively, we say that

velocity =1 slope of world line

in Galilean relativity. Notice that this works for negative slopes and velocities as well as positive ones. If the object changes its velocity with time, then the world line is curved, and the instantaneous velocity at any time is the inverse of the slope of the tangent to the world line at that time.

The hardest thing to realize about spacetime diagrams is that they represent the past, present, and future all in one diagram. Thus, spacetime diagrams don’t change with time — the evolution of physical systems is represented by looking at successive horizontal slices in the diagram at successive times. Spacetime diagrams represent evolution, but they don’t evolve themselves.

The principle of relativity states that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial reference frames. An inertial reference frame is one that is not accelerated. Reference frames attached to a car at rest and to a car moving steadily down the freeway at 30 m s-1 are both inertial. A reference frame attached to a car accelerating away from a stop light is not inertial.

The principle of relativity is an educated guess or hypothesis based on extensive experience. If the principle of relativity weren’t true, we would have to do all our calculations in some preferred reference frame. This would be very annoying. However, the more fundamental problem is that we have no idea what the velocity of this preferred frame might be. Does it move with the earth? That would be very earth-centric. How about the velocity of the center of our galaxy or the mean velocity of all the galaxies? Rather than face the issue of a preferred reference frame, physicists have chosen to stick with the principle of relativity.

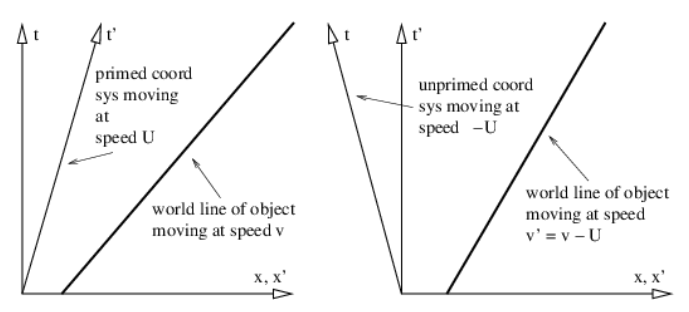

If an object is moving to the left at velocity v relative to a particular reference frame, it appears to be moving at a velocity v′=v−U relative to another reference frame which itself is moving at velocity U. This is the Galilean velocity transformation law, and it is based on everyday experience. If you are traveling 30 m s-1 down the freeway and another car passes you doing 40 m s-1, then the other car moves past you at 10 m s-1 relative to your car.

Figure 4.1.2: shows how the world line of an object is represented differently in the unprimed (x, t) and primed (x′, t′) reference frames. The difference between the velocity of the object and the velocity of the primed frame (i. e., the difference in the inverses of the slopes of the corresponding world lines) is the same in both reference frames in this Galilean case. This illustrates the difference between a physical law independent of reference frame (the difference between velocities in Galilean relativity) and the different motion of the object in the two different reference frames.