4.6: Relative Motion in One and Two Dimensions

- Page ID

- 3989

- Explain the concept of reference frames.

- Write the position and velocity vector equations for relative motion.

- Draw the position and velocity vectors for relative motion.

- Analyze one-dimensional and two-dimensional relative motion problems using the position and velocity vector equations.

Motion does not happen in isolation. If you’re riding in a train moving at 10 m/s east, this velocity is measured relative to the ground on which you’re traveling. However, if another train passes you at 15 m/s east, your velocity relative to this other train is different from your velocity relative to the ground. Your velocity relative to the other train is 5 m/s west. To explore this idea further, we first need to establish some terminology.

Reference Frames

To discuss relative motion in one or more dimensions, we first introduce the concept of reference frames. When we say an object has a certain velocity, we must state it has a velocity with respect to a given reference frame. In most examples we have examined so far, this reference frame has been Earth. If you say a person is sitting in a train moving at 10 m/s east, then you imply the person on the train is moving relative to the surface of Earth at this velocity, and Earth is the reference frame. We can expand our view of the motion of the person on the train and say Earth is spinning in its orbit around the Sun, in which case the motion becomes more complicated. In this case, the solar system is the reference frame. In summary, all discussion of relative motion must define the reference frames involved. We now develop a method to refer to reference frames in relative motion.

Relative Motion in One Dimension

We introduce relative motion in one dimension first, because the velocity vectors simplify to having only two possible directions. Take the example of the person sitting in a train moving east. If we choose east as the positive direction and Earth as the reference frame, then we can write the velocity of the train with respect to the Earth as \(\vec{v}_{TE}\) = 10 m/s \(\hat{i}\) east, where the subscripts TE refer to train and Earth. Let’s now say the person gets up out of /her seat and walks toward the back of the train at 2 m/s. This tells us she has a velocity relative to the reference frame of the train. Since the person is walking west, in the negative direction, we write her velocity with respect to the train as \(\vec{v}_{PT}\) = −2 m/s \(\hat{i}\). We can add the two velocity vectors to find the velocity of the person with respect to Earth. This relative velocity is written as

\[\vec{v}_{PE} = \vec{v}_{PT} + \vec{v}_{TE} \ldotp \label{4.33}\]

Note the ordering of the subscripts for the various reference frames in Equation \ref{4.33}. The subscripts for the coupling reference frame, which is the train, appear consecutively in the right-hand side of the equation. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the correct order of subscripts when forming the vector equation.

Adding the vectors, we find \(\vec{v}_{PE}\) = 8 m/s \(\hat{i}\), so the person is moving 8 m/s east with respect to Earth. Graphically, this is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Relative Velocity in Two Dimensions

We can now apply these concepts to describing motion in two dimensions. Consider a particle P and reference frames S and S′, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The position of the origin of S′ as measured in S is \(\vec{r}_{S'S}\), the position of P as measured in S′ is \(\vec{r}_{PS'}\), and the position of P as measured in S is \(\vec{r}_{PS}\).

From Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) we see that

\[\vec{r}_{PS} = \vec{r}_{PS} + \vec{r}_{S'S} \ldotp \label{4.34}\]

The relative velocities are the time derivatives of the position vectors. Therefore,

\[\vec{v}_{PS} = \vec{v}_{PS'} + \vec{v}_{S'S} \ldotp \label{4.35}\]

The velocity of a particle relative to S is equal to its velocity relative to S′ plus the velocity of S′ relative to S.

We can extend Equation \ref{4.35} to any number of reference frames. For particle P with velocities \(\vec{v}_{PA}\), \(\vec{v}_{PB}\), and \(\vec{v}_{PC}\) in frames A, B, and C,

\[\vec{v}_{PC} = \vec{v}_{PA} + \vec{v}_{AB} + \vec{v}_{BC} \ldotp \label{4.36}\]

We can also see how the accelerations are related as observed in two reference frames by differentiating Equation \ref{4.35}:

\[\vec{a}_{PS} = \vec{a}_{PS'} + \vec{a}_{S'S} \ldotp \label{4.37}\]

We see that if the velocity of S′ relative to S is a constant, then \(\vec{a}_{S'S}\) = 0 and

\[\vec{a}_{PS} = \vec{a}_{PS'} \ldotp \label{4.38}\]

This says the acceleration of a particle is the same as measured by two observers moving at a constant velocity relative to each other.

A truck is traveling south at a speed of 70 km/h toward an intersection. A car is traveling east toward the intersection at a speed of 80 km/h (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). What is the velocity of the car relative to the truck?

Strategy

First, we must establish the reference frame common to both vehicles, which is Earth. Then, we write the velocities of each with respect to the reference frame of Earth, which enables us to form a vector equation that links the car, the truck, and Earth to solve for the velocity of the car with respect to the truck.

Solution

The velocity of the car with respect to Earth is \(\vec{v}_{CE}\) = 80 km/h \(\hat{i}\). The velocity of the truck with respect to Earth is \(\vec{v}_{TE}\) = −70 km/h \(\hat{j}\). Using the velocity addition rule, the relative motion equation we are seeking is

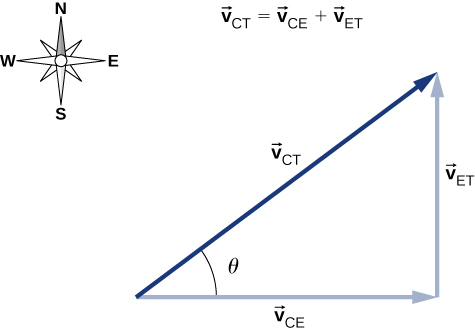

\[\vec{v}_{CT} = \vec{v}_{CE} + \vec{v}_{ET} \ldotp \label{ex2}\]

Here, \(\vec{v}_{CT}\) is the velocity of the car with respect to the truck, and Earth is the connecting reference frame. Since we have the velocity of the truck with respect to Earth, the negative of this vector is the velocity of Earth with respect to the truck: \(\vec{v}_{ET} = − \vec{v}_{TE}\). The vector diagram of this equation is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

We can now solve for the velocity of the car with respect to the truck:

\[\big| \vec{v}_{CT} \big| = \sqrt{(80.0\; km/h)^{2} + (70.0\; km/h)^{2}} = 106.\; km/h \nonumber\]

and

\[\theta = \tan^{-1} \left(\dfrac{70.0}{80.0}\right) = 41.2^{o}\; north\; of\; east \ldotp \nonumber\]

Significance

Drawing a vector diagram showing the velocity vectors can help in understanding the relative velocity of the two objects.

A boat heads north in still water at 4.5 m/s directly across a river that is running east at 3.0 m/s. What is the velocity of the boat with respect to Earth?

A pilot must fly his plane due north to reach his destination. The plane can fly at 300 km/h in still air. A wind is blowing out of the northeast at 90 km/h. (a) What is the speed of the plane relative to the ground? (b) In what direction must the pilot head her plane to fly due north?

Strategy

The pilot must point her plane somewhat east of north to compensate for the wind velocity. We need to construct a vector equation that contains the velocity of the plane with respect to the ground, the velocity of the plane with respect to the air, and the velocity of the air with respect to the ground. Since these last two quantities are known, we can solve for the velocity of the plane with respect to the ground. We can graph the vectors and use this diagram to evaluate the magnitude of the plane’s velocity with respect to the ground. The diagram will also tell us the angle the plane’s velocity makes with north with respect to the air, which is the direction the pilot must head her plane.

Solution

The vector equation is \(\vec{v}_{PG} = \vec{v}_{PA} + \vec{v}_{AG}\), where P = plane, A = air, and G = ground. From the geometry in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), we can solve easily for the magnitude of the velocity of the plane with respect to the ground and the angle of the plane’s heading, \(\theta\).

- Known quantities: $$\big| \vec{v}_{PA} \big| = 300\; km/h$$ $$\big| \vec{v}_{AG} \big| = 90\; km/h$$Substituting into the equation of motion, we obtain \(\big| \vec{v}_{PG} \big|\) = 230 km/h.

- The angle \(\theta\) = tan−1 \(\left(\dfrac{63.64}{300}\right)\) = 12° east of north.