15.4: Comparing Simple Harmonic Motion and Circular Motion

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Describe how the sine and cosine functions relate to the concepts of circular motion

- Describe the connection between simple harmonic motion and circular motion

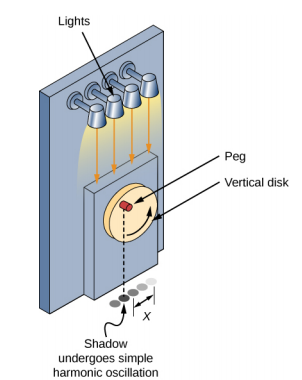

An easy way to model Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) is by considering uniform circular motion. Figure 15.4.1 shows one way of using this method. A peg (a cylinder of wood) is attached to a vertical disk, rotating with a constant angular frequency.

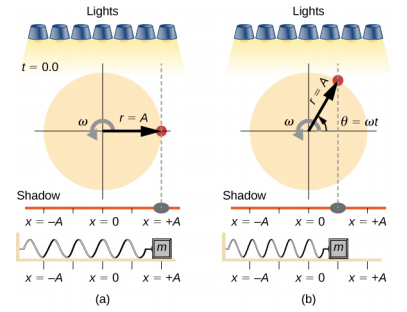

Figure 15.4.2 shows a side view of the disk and peg. If a lamp is placed above the disk and peg, the peg produces a shadow. Let the disk have a radius of r = A and define the position of the shadow that coincides with the center line of the disk to be x = 0.00 m. As the disk rotates at a constant rate, the shadow oscillates between x = + A and x = −A. Now imagine a block on a spring beneath the floor as shown in Figure 15.4.2.

If the disk turns at the proper angular frequency, the shadow follows along with the block. The position of the shadow can be modeled with the equation

x(t)=Acos(ωt).

Recall that the block attached to the spring does not move at a constant velocity. How often does the wheel have to turn to have the peg’s shadow always on the block? The disk must turn at a constant angular frequency equal to 2π times the frequency of oscillation (ω = 2πf).

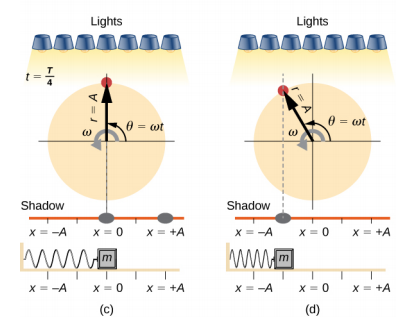

Figure 15.4.3 shows the basic relationship between uniform circular motion and SHM. The peg lies at the tip of the radius, a distance A from the center of the disk. The x-axis is defined by a line drawn parallel to the ground, cutting the disk in half. The y-axis (not shown) is defined by a line perpendicular to the ground, cutting the disk into a left half and a right half. The center of the disk is the point (x = 0, y = 0). The projection of the position of the peg onto the fixed x-axis gives the position of the shadow, which undergoes SHM analogous to the system of the block and spring. At the time shown in the figure, the projection has position x and moves to the left with velocity v. The tangential velocity of the peg around the circle equals ˉvmax of the block on the spring. The x-component of the velocity is equal to the velocity of the block on the spring.

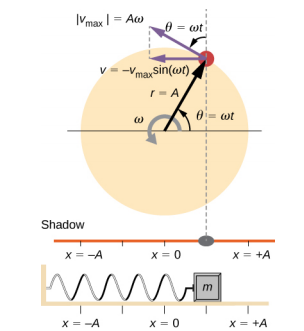

We can use Figure 15.4.3 to analyze the velocity of the shadow as the disk rotates. The peg moves in a circle with a speed of vmax = Aω. The shadow moves with a velocity equal to the component of the peg’s velocity that is parallel to the surface where the shadow is being produced:

v=−vmaxsin(ωt).

It follows that the acceleration is

a=−amaxcos(ωt).

Identify an object that undergoes uniform circular motion. Describe how you could trace the SHM of this object.