8.11: Gravitational Potential Energy and Total Energy

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Determine changes in gravitational potential energy over great distances

- Apply conservation of energy to determine escape velocity

- Determine whether astronomical bodies are gravitationally bound

We studied gravitational potential energy in Potential Energy and Conservation of Energy, where the value of g remained constant. We now develop an expression that works over distances such that g is not constant. This is necessary to correctly calculate the energy needed to place satellites in orbit or to send them on missions in space.

Gravitational Potential Energy beyond Earth

We defined work and potential energy, previously. The usefulness of those definitions is the ease with which we can solve many problems using conservation of energy. Potential energy is particularly useful for forces that change with position, as the gravitational force does over large distances. In Potential Energy and Conservation of Energy, we showed that the change in gravitational potential energy near Earth’s surface is

ΔU=mg(y2−y1)

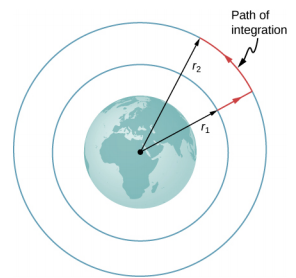

This works very well if g does not change significantly between y1 and y2. We return to the definition of work and potential energy to derive an expression that is correct over larger distances. Recall that work (W) is the integral of the dot product between force and distance. Essentially, it is the product of the component of a force along a displacement times that displacement. We define Δu as the negative of the work done by the force we associate with the potential energy. For clarity, we derive an expression for moving a mass m from distance r1 from the center of Earth to distance r2. However, the result can easily be generalized to any two objects changing their separation from one value to another.

Consider Figure 8.11.1, in which we take m from a distance r1 from Earth’s center to a distance that is r2 from the center. Gravity is a conservative force (its magnitude and direction are functions of location only), so we can take any path we wish, and the result for the calculation of work is the same. We take the path shown, as it greatly simplifies the integration. We first move radially outward from distance r1 to distance r2, and then move along the arc of a circle until we reach the final position. During the radial portion, →F is opposite to the direction we travel along d→r, so

E=K1+U1=K2+U2

Along the arc, →F is perpendicular to d→r, so →F⋅d→r = 0. No work is done as we move along the arc. Using the expression for the gravitational force and noting the values for →F⋅d→r along the two segments of our path, we have

ΔU=−∫r2r1→F⋅d→r=GMEm∫r2r1drr2=GMEm(1r1−1r2).

Since ΔU=U2−U1 we can adopt a simple expression for U:

U=−GMEmr.

Note two important items with this definition. First, U→0 as r→∞. The potential energy is zero when the two masses are infinitely far apart. Only the difference in U is important, so the choice of U=0 for r=∞ is merely one of convenience. (Recall that in earlier gravity problems, you were free to take U=0 at the top or bottom of a building, or anywhere.) Second, note that U becomes increasingly more negative as the masses get closer. That is consistent with what you learned about potential energy in Potential Energy and Conservation of Energy. As the two masses are separated, positive work must be done against the force of gravity, and hence, U increases (becomes less negative). All masses naturally fall together under the influence of gravity, falling from a higher to a lower potential energy.

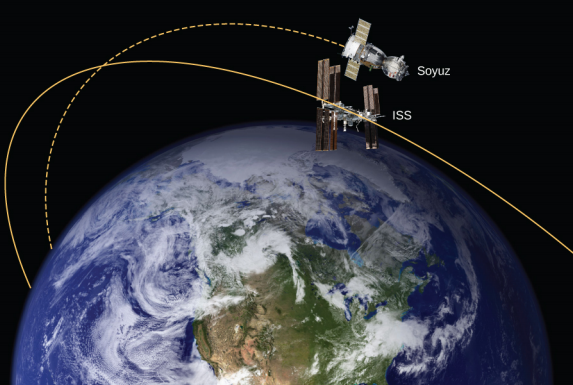

How much energy is required to lift the 9000-kg Soyuz vehicle from Earth’s surface to the height of the ISS, 400 km above the surface?

Strategy

Use Equation 8.11.5 to find the change in potential energy of the payload. That amount of work or energy must be supplied to lift the payload.

Solution

Paying attention to the fact that we start at Earth’s surface and end at 400 km above the surface, the change in U is

ΔU=Uorbit−UEarth=−GMEmRE+400km−(−GMEmRE).

We insert the values

- m=9000kg

- ME=5.96×1024kg

- RE=6.37×106m

and convert 400 km into 4.00 x 105 m. We find ΔU=3.32×1010J. It is positive, indicating an increase in potential energy, as we would expect.

Significance

For perspective, consider that the average US household energy use in 2013 was 909 kWh per month. That is energy of

909kWh×1000W/kW×3600s/h=3.27×109Jpermonth.

So our result is an energy expenditure equivalent to 10 months. However, this is just the energy needed to raise the payload 400 km. If we want the Soyuz to be in orbit so it can rendezvous with the ISS and not just fall back to Earth, it needs a lot of kinetic energy. As we see in the next section, that kinetic energy is about five times that of ΔU. In addition, far more energy is expended lifting the propulsion system itself. Space travel is not cheap.

Why not use the simpler expression in Equation ??? instead? How significant would the error be? (The value g at 400 km above the Earth is 8.67 m/s2.)

Conservation of Energy

In Potential Energy and Conservation of Energy, we described how to apply conservation of energy for systems with conservative forces. We were able to solve many problems, particularly those involving gravity, more simply using conservation of energy. Those principles and problem-solving strategies apply equally well here. The only change is to place the new expression for potential energy into the conservation of energy equation,

Etot=K1+U1=K2+U2.

12mv21−GMmr1=12mv22−GMmr2

Note that we use M, rather than ME, as a reminder that we are not restricted to problems involving Earth. However, we still assume that m << M. (For problems in which this is not true, we need to include the kinetic energy of both masses and use conservation of momentum to relate the velocities to each other. But the principle remains the same.)

Escape velocity

Escape velocity is often defined to be the minimum initial velocity of an object that is required to escape the surface of a planet (or any large body like a moon) and never return. As usual, we assume no energy lost to an atmosphere, should there be any.

Consider the case where an object is launched from the surface of a planet with an initial velocity directed away from the planet. With the minimum velocity needed to escape, the object would just come to rest infinitely far away, that is, the object gives up the last of its kinetic energy just as it reaches infinity, where the force of gravity becomes zero. Since U → 0 as r → ∞, this means the total energy is zero. Thus, we find the escape velocity from the surface of an astronomical body of mass M and radius R by setting the total energy equal to zero. At the surface of the body, the object is located at r1=R and it has escape velocity v1=vesc. It reaches r2=∞ with velocity v2=0. Substituting into Equation ???, we have

12mv2esc−GMmR=12m02−GMm∞=0.

Solving for the escape velocity,

vesc=√2GMR.

Notice that m has canceled out of the equation. The escape velocity is the same for all objects, regardless of mass. Also, we are not restricted to the surface of the planet; R can be any starting point beyond the surface of the planet.

What is the escape speed from the surface of Earth? Assume there is no energy loss from air resistance. Compare this to the escape speed from the Sun, starting from Earth’s orbit.

Strategy

We use Equation 13.6, clearly defining the values of R and M. To escape Earth, we need the mass and radius of Earth. For escaping the Sun, we need the mass of the Sun, and the orbital distance between Earth and the Sun.

Solution

Substituting the values for Earth’s mass and radius directly into Equation 13.6, we obtain

vesc=√2GMR=√2(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(5.96×1024kg)6.37×106m=1.12×104m/s.

That is about 11 km/s or 25,000 mph. To escape the Sun, starting from Earth’s orbit, we use R = RES = 1.50 x 1011 m and MSun = 1.99 x 1030 kg. The result is vesc = 4.21 x 104 m/s or about 42 km/s.

Significance

The speed needed to escape the Sun (leave the solar system) is nearly four times the escape speed from Earth’s surface. But there is help in both cases. Earth is rotating, at a speed of nearly 1.7 km/s at the equator, and we can use that velocity to help escape, or to achieve orbit. For this reason, many commercial space companies maintain launch facilities near the equator. To escape the Sun, there is even more help. Earth revolves about the Sun at a speed of approximately 30 km/s. By launching in the direction that Earth is moving, we need only an additional 12 km/s. The use of gravitational assist from other planets, essentially a gravity slingshot technique, allows space probes to reach even greater speeds. In this slingshot technique, the vehicle approaches the planet and is accelerated by the planet’s gravitational attraction. It has its greatest speed at the closest point of approach, although it decelerates in equal measure as it moves away. But relative to the planet, the vehicle’s speed far before the approach, and long after, are the same. If the directions are chosen correctly, that can result in a significant increase (or decrease if needed) in the vehicle’s speed relative to the rest of the solar system.

Energy and gravitationally bound objects

As stated previously, escape velocity can be defined as the initial velocity of an object that can escape the surface of a moon or planet. More generally, it is the speed at any position such that the total energy is zero. If the total energy is zero or greater, the object escapes. If the total energy is negative, the object cannot escape. Let’s see why that is the case.

As noted earlier, we see that U→0 as r→∞. If the total energy is zero, then as m reaches a value of r that approaches infinity, U becomes zero and so must the kinetic energy. Hence, m comes to rest infinitely far away from M. It has “just escaped” M. If the total energy is positive, then kinetic energy remains at r=∞ and certainly m does not return. When the total energy is zero or greater, then we say that m is not gravitationally bound to M.

On the other hand, if the total energy is negative, then the kinetic energy must reach zero at some finite value of r, where U is negative and equal to the total energy. The object can never exceed this finite distance from M, since to do so would require the kinetic energy to become negative, which is not possible. We say m is gravitationally bound to M.

We have simplified this discussion by assuming that the object was headed directly away from the planet. What is remarkable is that the result applies for any velocity. Energy is a scalar quantity and hence Equation ??? is a scalar equation—the direction of the velocity plays no role in conservation of energy. It is possible to have a gravitationally bound system where the masses do not “fall together,” but maintain an orbital motion about each other.

We have one important final observation. Earlier we stated that if the total energy is zero or greater, the object escapes. Strictly speaking, Equation ??? and Equation ??? apply for point objects. They apply to finite-sized, spherically symmetric objects as well, provided that the value for r in Equation ??? is always greater than the sum of the radii of the two objects. If r becomes less than this sum, then the objects collide. (Even for greater values of r, but near the sum of the radii, gravitational tidal forces could create significant effects if both objects are planet sized. We examine tidal effects in Tidal Forces.) Neither positive nor negative total energy precludes finite-sized masses from colliding. For real objects, direction is important.

Let’s consider the preceding example again, where we calculated the escape speed from Earth and the Sun, starting from Earth’s orbit. We noted that Earth already has an orbital speed of 30 km/s. As we see in the next section, that is the tangential speed needed to stay in circular orbit. If an object had this speed at the distance of Earth’s orbit, but was headed directly away from the Sun, how far would it travel before coming to rest? Ignore the gravitational effects of any other bodies.

Strategy

The object has initial kinetic and potential energies that we can calculate. When its speed reaches zero, it is at its maximum distance from the Sun. We use Equation 13.5, conservation of energy, to find the distance at which kinetic energy is zero.

Solution

The initial position of the object is Earth’s radius of orbit and the initial speed is given as 30 km/s. The final velocity is zero, so we can solve for the distance at that point from the conservation of energy equation. Using RES = 1.50 x 1011 m and MSun = 1.99 x 1030 kg, we have

12mv21−GMmr1=12mv22−GMmr212m(30km/s)2−(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(1.99×1030kg)m1.50×1011m=12m(0)2−(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(1.99×1030kg)mr2

where the mass m cancels. Solving for r2 we get r2 = 3.0 x 1011 m. Note that this is twice the initial distance from the Sun and takes us past Mars’s orbit, but not quite to the asteroid belt.

Significance

The object in this case reached a distance exactly twice the initial orbital distance. We will see the reason for this in the next section when we calculate the speed for circular orbits.

Assume you are in a spacecraft in orbit about the Sun at Earth’s orbit, but far away from Earth (so that it can be ignored). How could you redirect your tangential velocity to the radial direction such that you could then pass by Mars’s orbit? What would be required to change just the direction of the velocity?

More about Circular Orbits

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, Nicolaus Copernicus first suggested that Earth and all other planets orbit the Sun in circles. He further noted that orbital periods increased with distance from the Sun. Later analysis by Kepler showed that these orbits are actually ellipses, but the orbits of most planets in the solar system are nearly circular. Earth’s orbital distance from the Sun varies a mere 2%. The exception is the eccentric orbit of Mercury, whose orbital distance varies nearly 40%.

Determining the orbital speed and orbital period of a satellite is much easier for circular orbits, so we make that assumption in the derivation that follows. As we described in the previous section, an object with negative total energy is gravitationally bound and therefore is in orbit. Our computation for the special case of circular orbits will confirm this. We focus on objects orbiting Earth, but our results can be generalized for other cases.

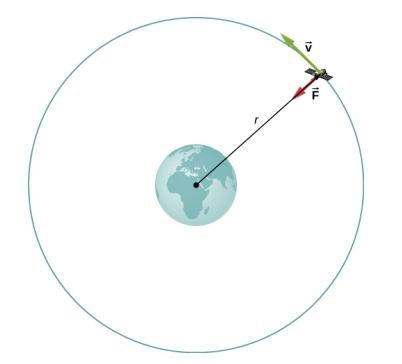

Consider a satellite of mass m in a circular orbit about Earth at distance r from the center of Earth (Figure 8.11.1). It has centripetal acceleration directed toward the center of Earth. Earth’s gravity is the only force acting, so Newton’s second law gives

We solve for the speed of the orbit, noting that m cancels, to get the orbital speed

Consistent with what we saw in g=GMEr2 and vesc=√2GMR, m does not appear in Equation ???. The value of g, the escape velocity, and orbital velocity depend only upon the distance from the center of the planet, and not upon the mass of the object being acted upon. Notice the similarity in the equations for vorbit and vesc. The escape velocity is exactly √2 times greater, about 40%, than the orbital velocity. This comparison was noted in Example 13.4.2, and it is true for a satellite at any radius.

To find the period of a circular orbit, we note that the satellite travels the circumference of the orbit 2πr in one period T. Using the definition of speed, we have

vorbit=2πrT.

We substitute this into Equation ??? and rearrange to get

T=2π√r3GME.

We see in the next section that this represents Kepler’s third law for the case of circular orbits. It also confirms Copernicus’s observation that the period of a planet increases with increasing distance from the Sun. We need only replace ME with MSun in Equation ???.

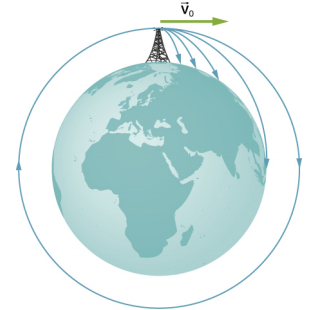

We conclude this section by returning to our earlier discussion about astronauts in orbit appearing to be weightless, as if they were free-falling towards Earth. In fact, they are in free fall. Consider the trajectories shown in Figure 8.11.2. (This figure is based on a drawing by Newton in his Principia and also appeared earlier in Motion in Two and Three Dimensions.) All the trajectories shown that hit the surface of Earth have less than orbital velocity. The astronauts would accelerate toward Earth along the noncircular paths shown and feel weightless. (Astronauts actually train for life in orbit by riding in airplanes that free fall for 30 seconds at a time.) But with the correct orbital velocity, Earth’s surface curves away from them at exactly the same rate as they fall toward Earth. Of course, staying the same distance from the surface is the point of a circular orbit.

We can summarize our discussion of orbiting satellites in the following Problem-Solving Strategy.

- Determine whether the equations for speed, energy, or period are valid for the problem at hand. If not, start with the first principles we used to derive those equations.

- To start from first principles, draw a free-body diagram and apply Newton’s law of gravitation and Newton’s second law.

- Along with the definitions for speed and energy, apply Newton’s second law of motion to the bodies of interest.

Determine the orbital speed and period for the International Space Station (ISS).

Strategy

Since the ISS orbits 4.00 x 102 km above Earth’s surface, the radius at which it orbits is RE + 4.00 x 102 km. We use Equations ??? and ??? to find the orbital speed and period, respectively.

Solution

Using Equation ???, the orbital velocity is

vorbit=√GMEr=√(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(5.96×1024kg)(6.36×106+4.00×105)m=7.67×103m/s

which is about 17,000 mph. Using Equation ???, the period is

T=2π√r3GME=2π√(6.36×106+4.00×105m)3(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(5.96×1024kg)=5.55×103s

which is just over 90 minutes.

Significance

The ISS is considered to be in low Earth orbit (LEO). Nearly all satellites are in LEO, including most weather satellites. GPS satellites, at about 20,000 km, are considered medium Earth orbit. The higher the orbit, the more energy is required to put it there and the more energy is needed to reach it for repairs. Of particular interest are the satellites in geosynchronous orbit. All fixed satellite dishes on the ground pointing toward the sky, such as TV reception dishes, are pointed toward geosynchronous satellites. These satellites are placed at the exact distance, and just above the equator, such that their period of orbit is 1 day. They remain in a fixed position relative to Earth’s surface.

By what factor must the radius change to reduce the orbital velocity of a satellite by one-half? By what factor would this change the period?

Determine the mass of Earth from the orbit of the Moon.

Strategy

We use Equation ???, solve for ME, and substitute for the period and radius of the orbit. The radius and period of the Moon’s orbit was measured with reasonable accuracy thousands of years ago. From the astronomical data in Appendix D, the period of the Moon is 27.3 days = 2.36 x 106 s, and the average distance between the centers of Earth and the Moon is 384,000 km.

Solution

Solving for ME,

T=2π√r3GMEME=2π2r3GT2=4π2(3.84×108m)3(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(2.36×106s)2=6.01×1024kg.

Significance

Compare this to the value of 5.96 x 1024 kg that we obtained in Example 13.3.3, using the value of g at the surface of Earth. Although these values are very close (~0.8%), both calculations use average values. The value of g varies from the equator to the poles by approximately 0.5%. But the Moon has an elliptical orbit in which the value of r varies just over 10%. (The apparent size of the full Moon actually varies by about this amount, but it is difficult to notice through casual observation as the time from one extreme to the other is many months.)

There is another consideration to this last calculation of ME. We derived Equation ??? assuming that the satellite orbits around the center of the astronomical body at the same radius used in the expression for the gravitational force between them. What assumption is made to justify this? Earth is about 81 times more massive than the Moon. Does the Moon orbit about the exact center of Earth?

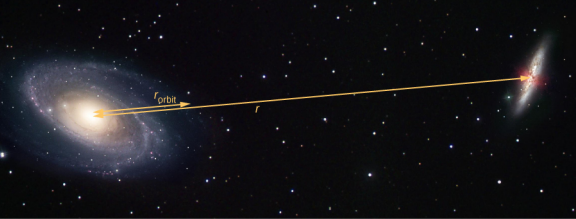

Let’s revisit Example 13.2.2. Assume that the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies are in a circular orbit about each other. What would be the velocity of each and how long would their orbital period be? Assume the mass of each is 800 billion solar masses and their centers are separated by 2.5 million light years.

Strategy

We cannot use Equations ??? and ??? directly because they were derived assuming that the object of mass m orbited about the center of a much larger planet of mass M. We determined the gravitational force in Example 13.2.2 using Newton’s law of universal gravitation. We can use Newton’s second law, applied to the centripetal acceleration of either galaxy, to determine their tangential speed. From that result we can determine the period of the orbit.

Solution

In Example 13.2.2, we found the force between the galaxies to be

F12=Gm1m2r2=(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)[(800×109)(2.0×1030)kg]2[(2.5×106)(9.5×1015)m]2=3.0×1029N

and that the acceleration of each galaxy is

a=Fm=3.0×1029N(800×109)(2.0×1030)kg=1.9×10−13m/s2.

Since the galaxies are in a circular orbit, they have centripetal acceleration. If we ignore the effect of other galaxies, then, as we learned in Linear Momentum and Collisions and Fixed-Axis Rotation, the centers of mass of the two galaxies remain fixed. Hence, the galaxies must orbit about this common center of mass. For equal masses, the center of mass is exactly half way between them. So the radius of the orbit, rorbit, is not the same as the distance between the galaxies, but one-half that value, or 1.25 million light-years. These two different values are shown in Figure 8.11.3.

Using the expression for centripetal acceleration, we have

ac=v2orbitrorbit1.9×10−13m/s2=v2orbit(1.25×106)(9.5×1015)m.

Solving for the orbit velocity, we have vorbit=47km/s. Finally, we can determine the period of the orbit directly from

T=2πrvorbit

to find that the period is T = 1.6 x 1018 s, about 50 billion years.

Significance

The orbital speed of 47 km/s might seem high at first. But this speed is comparable to the escape speed from the Sun, which we calculated in an earlier example. To give even more perspective, this period is nearly four times longer than the time that the Universe has been in existence.

In fact, the present relative motion of these two galaxies is such that they are expected to collide in about 4 billion years. Although the density of stars in each galaxy makes a direct collision of any two stars unlikely, such a collision will have a dramatic effect on the shape of the galaxies. Examples of such collisions are well known in astronomy

Galaxies are not single objects. How does the gravitational force of one galaxy exerted on the “closer” stars of the other galaxy compare to those farther away? What effect would this have on the shape of the galaxies themselves?

See the Sloan Digital Sky Survey page for more information on colliding galaxies.

Use this interactive simulation to move the Sun, Earth, Moon, and space station to see the effects on their gravitational forces and orbital paths. Visualize the sizes and distances between different heavenly bodies, and turn off gravity to see what would happen without it.

Energy in Circular Orbits

In Gravitational Potential Energy and Total Energy, we argued that objects are gravitationally bound if their total energy is negative. The argument was based on the simple case where the velocity was directly away or toward the planet. We now examine the total energy for a circular orbit and show that indeed, the total energy is negative. As we did earlier, we start with Newton’s second law applied to a circular orbit,

GmMEr2=mac=mv2rGmMEr=mv2.

In the last step, we multiplied by r on each side. The right side is just twice the kinetic energy, so we have

K=12mv2=GmME2r.

The total energy is the sum of the kinetic and potential energies, so our final result is

E=K+U=GmME2r−GmMEr=−GmME2r.

We can see that the total energy is negative, with the same magnitude as the kinetic energy. For circular orbits, the magnitude of the kinetic energy is exactly one-half the magnitude of the potential energy. Remarkably, this result applies to any two masses in circular orbits about their common center of mass, at a distance r from each other. The proof of this is left as an exercise. We will see in the next section that a very similar expression applies in the case of elliptical orbits.

In Example 13.4.1, we calculated the energy required to simply lift the 9000-kg Soyuz vehicle from Earth’s surface to the height of the ISS, 400 km above the surface. In other words, we found its change in potential energy. We now ask, what total energy change in the Soyuz vehicle is required to take it from Earth’s surface and put it in orbit with the ISS for a rendezvous (Figure 8.11.4)? How much of that total energy is kinetic energy?

Strategy

The energy required is the difference in the Soyuz’s total energy in orbit and that at Earth’s surface. We can use Equation ??? to find the total energy of the Soyuz at the ISS orbit. But the total energy at the surface is simply the potential energy, since it starts from rest. [Note that we do not use Equation ??? at the surface, since we are not in orbit at the surface.] The kinetic energy can then be found from the difference in the total energy change and the change in potential energy found in Example 13.4.1. Alternatively, we can use Equation ??? to find vorbit and calculate the kinetic energy directly from that. The total energy required is then the kinetic energy plus the change in potential energy found in Example 13.4.1.

Solution

From Equation ???, the total energy of the Soyuz in the same orbit as the ISS is

Eorbit=Korbit+Uorbit=−GmME2r=(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(9000kg)(5.96×1024kg)2(6.36×106+4.00×105m)=−2.65×1011J.

The total energy at Earth's surface is

Esurface=Ksurface+Usurface=0−GmMEr=−(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(9000kg)(5.96×1024kg)(6.36×106m)=−5.63×1011J.

The change in energy is

ΔE=Eorbit−Esurface=2.98x1011J.

To get the kinetic energy, we subtract the change in potential energy from Example 13.4.1, ΔU = 3.32 x 1010 J. That gives us Korbit = (2.98 x 1011) − (3.32 x 1010) = 2.65 x 1011 J. As stated earlier, the kinetic energy of a circular orbit is always one-half the magnitude of the potential energy, and the same as the magnitude of the total energy. Our result confirms this.

The second approach is to use Equation ??? to find the orbital speed of the Soyuz, which we did for the ISS in Example 8.11.1.

vorbit=√GMEr=√(6.67×10−11N⋅m2/kg2)(5.96×1024kg)(6.36×106+4.00×105)m=7.67×103m/s

So the kinetic energy of the Soyuz in orbit is

Korbit=12mv2orbit=12(9000kg)(7.67×103m/s)2=2.65×1011J,

the same as in the previous method. The total energy is just

Eorbit=Korbit+ΔU=(2.65×1011)+(3.32×1010)=2.95×1011J.

Significance

The kinetic energy of the Soyuz is nearly eight times the change in its potential energy, or 90% of the total energy needed for the rendezvous with the ISS. And it is important to remember that this energy represents only the energy that must be given to the Soyuz. With our present rocket technology, the mass of the propulsion system (the rocket fuel, its container and combustion system) far exceeds that of the payload, and a tremendous amount of kinetic energy must be given to that mass. So the actual cost in energy is many times that of the change in energy of the payload itself.