12.4: Pulsars and the Discovery of Neutron Stars

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the research method that led to the discovery of neutron stars, located hundreds or thousands of light-years away

- Describe the features of a neutron star that allow it to be detected as a pulsar

- List the observational evidence that links pulsars and neutron stars to supernovae

After a type II supernova explosion fades away, all that is left behind is either a neutron star or something even more strange, a black hole. We will describe the properties of black holes in Black Holes and Curved Spacetime, but for now, we want to examine how the neutron stars we discussed earlier might become observable.

Neutron stars are the densest objects in the universe; the force of gravity at their surface is 1011 times greater than what we experience at Earth’s surface. The interior of a neutron star is composed of about 95% neutrons, with a small number of protons and electrons mixed in. In effect, a neutron star is a giant atomic nucleus, with a mass about 1057 times the mass of a proton. Its diameter is more like the size of a small town or an asteroid than a star. (Table 12.4.1 compares the properties of neutron stars and white dwarfs.) Because it is so small, a neutron star probably strikes you as the object least likely to be observed from thousands of light-years away. Yet neutron stars do manage to signal their presence across vast gulfs of space.

| Table 12.4.1: Properties of a Typical White Dwarf and a Neutron Star | ||

|---|---|---|

| Property | White Dwarf | Neutron Star |

| Mass (Sun = 1) | 0.6 (always <1.4) | Always >1.4 and <3 |

| Radius | 7000 km | 10 km |

| Density | 8 × 105 g/cm3 | 1014 g/cm3 |

The Discovery of Neutron Stars

In 1967, Jocelyn Bell, a research student at Cambridge University, was studying distant radio sources with a special detector that had been designed and built by her advisor Antony Hewish to find rapid variations in radio signals. The project computers spewed out reams of paper showing where the telescope had surveyed the sky, and it was the job of Hewish’s graduate students to go through it all, searching for interesting phenomena. In September 1967, Bell discovered what she called “a bit of scruff”—a strange radio signal unlike anything seen before.

What Bell had found, in the constellation of Vulpecula, was a source of rapid, sharp, intense, and extremely regular pulses of radio radiation. Like the regular ticking of a clock, the pulses arrived precisely every 1.33728 seconds. Such exactness first led the scientists to speculate that perhaps they had found signals from an intelligent civilization. Radio astronomers even half-jokingly dubbed the source “LGM” for “little green men.” Soon, however, three similar sources were discovered in widely separated directions in the sky.

When it became apparent that this type of radio source was fairly common, astronomers concluded that they were highly unlikely to be signals from other civilizations. By today, more than 2500 such sources have been discovered; they are now called pulsars, short for “pulsating radio sources.”

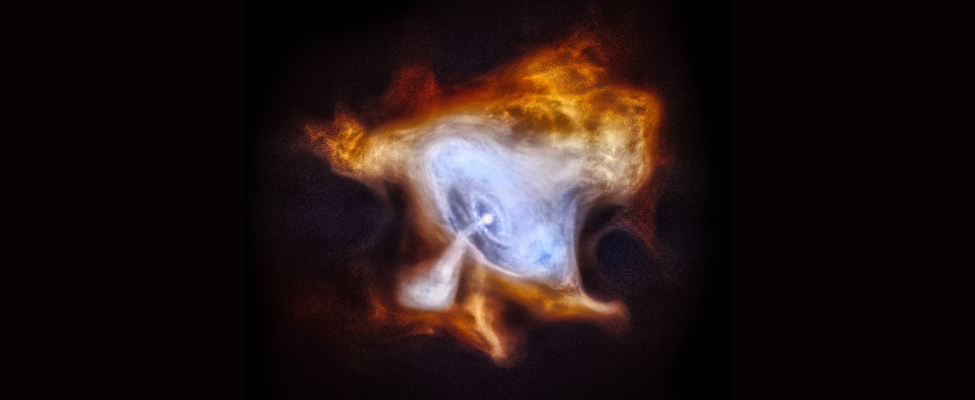

The pulse periods of different pulsars range from a little longer than 1/1000 of a second to nearly 10 seconds. At first, the pulsars seemed particularly mysterious because nothing could be seen at their location on visible-light photographs. But then a pulsar was discovered right in the center of the Crab Nebula, a cloud of gas produced by SN 1054, a supernova that was recorded by the Chinese in 1054 (Figure 12.4.1). The energy from the Crab Nebula pulsar arrives in sharp bursts that occur 30 times each second—with a regularity that would be the envy of a Swiss watchmaker. In addition to pulses of radio energy, we can observe pulses of visible light and X-rays from the Crab Nebula. The fact that the pulsar was just in the region of the supernova remnant where we expect the leftover neutron star to be immediately alerted astronomers that pulsars might be connected with these elusive “corpses” of massive stars.

The Crab Nebula is a fascinating object. The whole nebula glows with radiation at many wavelengths, and its overall energy output is more than 100,000 times that of the Sun—not a bad trick for the remnant of a supernova that exploded almost a thousand years ago. Astronomers soon began to look for a connection between the pulsar and the large energy output of the surrounding nebula.

View an interesting interview with Jocelyn Bell (Burnell) to learn about her life and work (this is part of a project at the American Institute of Physics to record interviews with pathbreaking scientists while they are still alive).

A Spinning Lighthouse Model

By applying a combination of theory and observation, astronomers eventually concluded that pulsars must be spinning neutron stars. According to this model, a neutron star is something like a lighthouse on a rocky coast (Figure 12.4.2). To warn ships in all directions and yet not cost too much to operate, the light in a modern lighthouse turns, sweeping its beam across the dark sea. From the vantage point of a ship, you see a pulse of light each time the beam points in your direction. In the same way, radiation from a small region on a neutron star sweeps across the oceans of space, giving us a pulse of radiation each time the beam points toward Earth.

Neutron stars are ideal candidates for such a job because the collapse has made them so small that they can turn very rapidly. Recall the principle of the conservation of angular momentum from Newton’s Great Synthesis: if an object gets smaller, it can spin more rapidly. Even if the parent star was rotating very slowly when it was on the main sequence, its rotation had to speed up as it collapsed to form a neutron star. With a diameter of only 10 to 20 kilometers, a neutron star can complete one full spin in only a fraction of a second. This is just the sort of time period we observe between pulsar pulses.

Any magnetic field that existed in the original star will be highly compressed when the core collapses to a neutron star. At the surface of the neutron star, in the outer layer consisting of ordinary matter (and not just pure neutrons), protons and electrons are caught up in this spinning field and accelerated nearly to the speed of light. In only two places—the north and south magnetic poles—can the trapped particles escape the strong hold of the magnetic field (Figure 12.4.3). The same effect can be seen (in reverse) on Earth, where charged particles from space are kept out by our planet’s magnetic field everywhere except near the poles. As a result, Earth’s auroras (caused when charged particles hit the atmosphere at high speed) are seen mainly near the poles.

Note that in a neutron star, the magnetic north and south poles do not have to be anywhere close to the north and south poles defined by the star’s rotation. In the same way, we discussed in the chapter on The Giant Planets that the magnetic poles on the planets Uranus and Neptune are not lined up with the poles of the planet’s spin. Figure 12.4.3 shows the poles of the magnetic field perpendicular to the poles of rotation, but the two kinds of poles could make any angle.

In fact, the misalignment of the rotational axis with the magnetic axis plays a crucial role in the generation of the observed pulses in this model. At the two magnetic poles, the particles from the neutron star are focused into a narrow beam and come streaming out of the whirling magnetic region at enormous speeds. They emit energy over a broad range of the electromagnetic spectrum. The radiation itself is also confined to a narrow beam, which explains why the pulsar acts like a lighthouse. As the rotation carries first one and then the other magnetic pole of the star into our view, we see a pulse of radiation each time.

Tests of the Model

This explanation of pulsars in terms of beams of radiation from highly magnetic and rapidly spinning neutron stars is a very clever idea. But what evidence do we have that it is the correct model? First, we can measure the masses of some pulsars, and they do turn out be in the range of 1.4 to 1.8 times that of the Sun—just what theorists predict for neutron stars. The masses are found using Kepler’s law for those few pulsars that are members of binary star systems.

But there is an even-better confirming argument, which brings us back to the Crab Nebula and its vast energy output. When the high-energy charged particles from the neutron star pulsar hit the slower-moving material from the supernova, they energize this material and cause it to “glow” at many different wavelengths—just what we observe from the Crab Nebula. The pulsar beams are a power source that “light up” the nebula long after the initial explosion of the star that made it.

Who “pays the bills” for all the energy we see coming out of a remnant like the Crab Nebula? After all, when energy emerges from one place, it must be depleted in another. The ultimate energy source in our model is the rotation of the neutron star, which propels charged particles outward and spins its magnetic field at enormous speeds. As its rotational energy is used to excite the Crab Nebula year after year, the pulsar inside the nebula slows down. As it slows, the pulses come a little less often; more time elapses before the slower neutron star brings its beam back around.

Several decades of careful observations have now shown that the Crab Nebula pulsar is not a perfectly regular clock as we originally thought: instead, it is gradually slowing down. Having measured how much the pulsar is slowing down, we can calculate how much rotation energy the neutron star is losing. Remember that it is very densely packed and spins amazingly quickly. Even a tiny slowing down can mean an immense loss of energy.

To the satisfaction of astronomers, the rotational energy lost by the pulsar turns out to be the same as the amount of energy emerging from the nebula surrounding it. In other words, the slowing down of a rotating neutron star can explain precisely why the Crab Nebula is glowing with the amount of energy we observe.

The Evolution of Pulsars

From observations of the pulsars discovered so far, astronomers have concluded that one new pulsar is born somewhere in the Galaxy every 25 to 100 years, the same rate at which supernovae are estimated to occur. Calculations suggest that the typical lifetime of a pulsar is about 10 million years; after that, the neutron star no longer rotates fast enough to produce significant beams of particles and energy, and is no longer observable. We estimate that there are about 100 million neutron stars in our Galaxy, most of them rotating too slowly to come to our notice.

The Crab pulsar is rather young (only about 960 years old) and has a short period, whereas other, older pulsars have already slowed to longer periods. Pulsars thousands of years old have lost too much energy to emit appreciably in the visible and X-ray wavelengths, and they are observed only as radio pulsars; their periods are a second or longer.

There is one other reason we can see only a fraction of the pulsars in the Galaxy. Consider our lighthouse model again. On Earth, all ships approach on the same plane—the surface of the ocean—so the lighthouse can be built to sweep its beam over that surface. But in space, objects can be anywhere in three dimensions. As a given pulsar’s beam sweeps over a circle in space, there is absolutely no guarantee that this circle will include the direction of Earth. In fact, if you think about it, many more circles in space will not include Earth than will include it. Thus, we estimate that we are unable to observe a large number of neutron stars because their pulsar beams miss us entirely.

At the same time, it turns out that only a few of the pulsars discovered so far are embedded in the visible clouds of gas that mark the remnant of a supernova. This might at first seem mysterious, since we know that supernovae give rise to neutron stars and we should expect each pulsar to have begun its life in a supernova explosion. But the lifetime of a pulsar turns out to be about 100 times longer than the length of time required for the expanding gas of a supernova remnant to disperse into interstellar space. Thus, most pulsars are found with no other trace left of the explosion that produced them.

In addition, some pulsars are ejected by a supernova explosion that is not the same in all directions. If the supernova explosion is stronger on one side, it can kick the pulsar entirely out of the supernova remnant (some astronomers call this “getting a birth kick”). We know such kicks happen because we see a number of young supernova remnants in nearby galaxies where the pulsar is to one side of the remnant and racing away at several hundred miles per second (Figure 12.4.4).

Touched by a neutron star

On December 27, 2004, Earth was bathed with a stream of X-ray and gamma-ray radiation from a neutron star known as SGR 1806-20. What made this event so remarkable was that, despite the distance of the source, its tidal wave of radiation had measurable effects on Earth’s atmosphere. The apparent brightness of this gamma-ray flare was greater than any historical star explosion.

The primary effect of the radiation was on a layer high in Earth’s atmosphere called the ionosphere. At night, the ionosphere is normally at a height of about 85 kilometers, but during the day, energy from the Sun ionizes more molecules and lowers the boundary of the ionosphere to a height of about 60 kilometers. The pulse of X-ray and gamma-ray radiation produced about the same level of ionization as the daytime Sun. It also caused some sensitive satellites above the atmosphere to shut down their electronics.

Measurements by telescopes in space indicate that SGR 1806-20 was a special type of fast-spinning neutron star called a magnetar. Astronomers Robert Duncan and Christopher Thomson gave them this name because their magnetic fields are stronger than that of any other type of astronomical source—in this case, about 800 trillion times stronger than the magnetic field of Earth.

A magnetar is thought to consist of a superdense core of neutrons surrounded by a rigid crust of atoms about a mile deep with a surface made of iron. The magnetar’s field is so strong that it creates huge stresses inside that can sometimes crack open the hard crust, causing a starquarke. The vibrating crust produces an enormous blast of radiation. An astronaut 0.1 light-year from this particular magnetar would have received a fatal does from the blast in less than a second.

Fortunately, we were far enough away from magnetar SGR 1806-20 to be safe. Could a magnetar ever present a real danger to Earth? To produce enough energy to disrupt the ozone layer, a magnetar would have to be located within the cloud of comets that surround the solar system, and we know no magnetars are that close. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating discovery that events on distant star corpses can have measurable effects on Earth.

Key Concepts and Summary

At least some supernovae leave behind a highly magnetic, rapidly rotating neutron star, which can be observed as a pulsar if its beam of escaping particles and focused radiation is pointing toward us. Pulsars emit rapid pulses of radiation at regular intervals; their periods are in the range of 0.001 to 10 seconds. The rotating neutron star acts like a lighthouse, sweeping its beam in a circle and giving us a pulse of radiation when the beam sweeps over Earth. As pulsars age, they lose energy, their rotations slow, and their periods increase.

Glossary

- pulsar

- a variable radio source of small physical size that emits very rapid radio pulses in very regular periods that range from fractions of a second to several seconds; now understood to be a rotating, magnetic neutron star that is energetic enough to produce a detectable beam of radiation and particles

Contributors and Attributions

Andrew Fraknoi (Foothill College), David Morrison (NASA Ames Research Center), Sidney C. Wolff (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) with many contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy).