8.4: Work-Energy Theorem

- Last updated

- Jun 17, 2019

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 18190

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

- Apply the work-energy theorem to find information about the motion of a particle, given the forces acting on it

- Use the work-energy theorem to find information about the forces acting on a particle, given information about its motion

We have discussed how to find the work done on a particle by the forces that act on it, but how is that work manifested in the motion of the particle? According to Newton’s second law of motion, the sum of all the forces acting on a particle, or the net force, determines the rate of change in the momentum of the particle, or its motion. Therefore, we should consider the work done by all the forces acting on a particle, or the net work, to see what effect it has on the particle’s motion.

Let’s start by looking at the net work done on a particle as it moves over an infinitesimal displacement, which is the dot product of the net force and the displacement:

dWnet=→Fnet⋅d→r.

Newton’s second law tells us that

→Fnet=m(d→vdt)

so

dWnet=m(d→vdt)⋅d→r.

For the mathematical functions describing the motion of a physical particle, we can rearrange the differentials dt, etc., as algebraic quantities in this expression, that is,

dWnet=m(d→vdt)⋅d→r=md→v⋅(d→rdt)=m→v⋅d→v,

where we substituted the velocity for the time derivative of the displacement and used the commutative property of the dot product. Since derivatives and integrals of scalars are probably more familiar to you at this point, we express the dot product in terms of Cartesian coordinates before we integrate between any two points A and B on the particle’s trajectory. This gives us the net work done on the particle:

Wnet,AB=∫BA(mvxdvx+mvydvy+mvzdvz=12m|v2x+v2y+v2z|BA=|12mv2|BA=KB−KA.

In the middle step, we used the fact that the square of the velocity is the sum of the squares of its Cartesian components, and in the last step, we used the definition of the particle’s kinetic energy. This important result is called the work-energy theorem.

Work-Energy Theorem

The net work done on a particle equals the change in the particle’s kinetic energy:

Wnet=KB−KA.

According to this theorem, when an object slows down, its final kinetic energy is less than its initial kinetic energy, the change in its kinetic energy is negative, and so is the net work done on it. If an object speeds up, the net work done on it is positive. When calculating the net work, you must include all the forces that act on an object. If you leave out any forces that act on an object, or if you include any forces that do not act on it, you will get a wrong result.

The importance of the work-energy theorem, and the further generalizations to which it leads, is that it makes some types of calculations much simpler to accomplish than they would be by trying to solve Newton’s second law. For example, in the section on Newton’s Laws of Motion, we found the speed of an object sliding down a frictionless plane by solving Newton’s second law for the acceleration and using kinematic equations for constant acceleration, obtaining

v2f=v2i+2g(sf−si)sinθ,

where s is the displacement down the plane.

We can also get this result from the work-energy theorem (Equation ???). Since only two forces are acting on the object—gravity and the normal force—and the normal force does not do any work, the net work is just the work done by gravity. This only depends on the object’s weight and the difference in height, so

Wnet=Wgrav=−mg(yf−yi),

where y is positive up. The work-energy theorem says that this equals the change in kinetic energy:

−mg(yf−yi)=12(v2f−v2i).

Using a right triangle, we can see that

(yf−yi)=(sf−s−i)sinθ,

so the result for the final speed is the same.

What is gained by using the work-energy theorem? The answer is that for a frictionless plane surface, not much. However, Newton’s second law is easy to solve only for this particular case, whereas the work-energy theorem gives the final speed for any shaped frictionless surface. For an arbitrary curved surface, the normal force is not constant, and Newton’s second law may be difficult or impossible to solve analytically. Constant or not, for motion along a surface, the normal force never does any work, because it’s perpendicular to the displacement. A calculation using the work-energy theorem avoids this difficulty and applies to more general situations.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Work-Energy Theorem

- Draw a free-body diagram for each force on the object.

- Determine whether or not each force does work over the displacement in the diagram. Be sure to keep any positive or negative signs in the work done.

- Add up the total amount of work done by each force.

- Set this total work equal to the change in kinetic energy and solve for any unknown parameter.

- Check your answers. If the object is traveling at a constant speed or zero acceleration, the total work done should be zero and match the change in kinetic energy. If the total work is positive, the object must have sped up or increased kinetic energy. If the total work is negative, the object must have slowed down or decreased kinetic energy

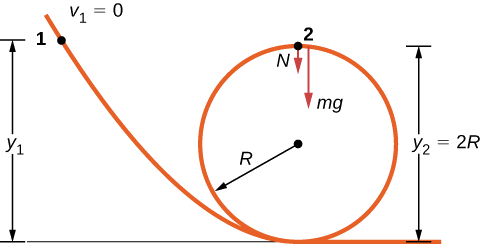

Example 8.4.1: Loop-the-Loop

The frictionless track for a toy car includes a loop-the-loop of radius R. How high, measured from the bottom of the loop, must the car be placed to start from rest on the approaching section of track and go all the way around the loop?

Strategy

The free-body diagram at the final position of the object is drawn in Figure 8.4.2. The gravitational work is the only work done over the displacement that is not zero. Since the weight points in the same direction as the net vertical displacement, the total work done by the gravitational force is positive. From the work-energy theorem, the starting height determines the speed of the car at the top of the loop,

mg(y2−y1)=12mv22,

where the notation is shown in the accompanying figure. At the top of the loop, the normal force and gravity are both down and the acceleration is centripetal, so

atop=Fm=N+mgm=v22R.

The condition for maintaining contact with the track is that there must be some normal force, however slight; that is, N>0. Substituting for v22 and N, we can find the condition for y1.

Solution

Implement the steps in the strategy to arrive at the desired result:

N=−mg+mv22R=−mgR+2mg(y1−2R)R>0ory1>5R2.

Significance

On the surface of the loop, the normal component of gravity and the normal contact force must provide the centripetal acceleration of the car going around the loop. The tangential component of gravity slows down or speeds up the car. A child would find out how high to start the car by trial and error, but now that you know the work-energy theorem, you can predict the minimum height (as well as other more useful results) from physical principles. By using the work-energy theorem, you did not have to solve a differential equation to determine the height.

Exercise 8.4.1

Suppose the radius of the loop-the-loop in Example 8.4.1 is 15 cm and the toy car starts from rest at a height of 45 cm above the bottom. What is its speed at the top of the loop?

In situations where the motion of an object is known, but the values of one or more of the forces acting on it are not known, you may be able to use the work-energy theorem to get some information about the forces. Work depends on the force and the distance over which it acts, so the information is provided via their product.

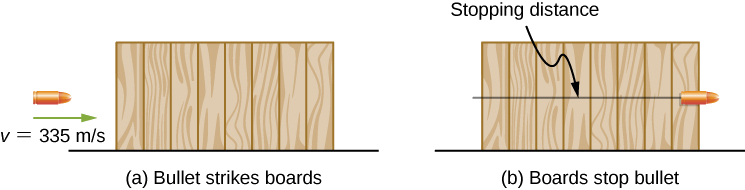

Example 8.4.2: Determining a Stopping Force

A bullet has a mass of 40 grains (2.60 g) and a muzzle velocity of 1100 ft./s (335 m/s). It can penetrate eight 1-inch pine boards, each with thickness 0.75 inches. What is the average stopping force exerted by the wood, as shown in Figure 8.4.3?

Strategy

We can assume that under the general conditions stated, the bullet loses all its kinetic energy penetrating the boards, so the work-energy theorem says its initial kinetic energy is equal to the average stopping force times the distance penetrated. The change in the bullet’s kinetic energy and the net work done stopping it are both negative, so when you write out the work-energy theorem, with the net work equal to the average force times the stopping distance, that’s what you get. The total thickness of eight 1-inch pine boards that the bullet penetrates is 8 x 34 in. = 6 in. = 15.2 cm.

Solution

Applying the work-energy theorem, we get

Wnet=−FaveΔsstop=−Kinitial,

so

Fave=12mv2Δsstop=12(2.66×10−3kg)(335m/s)20.152m=960N.

Significance

We could have used Newton’s second law and kinematics in this example, but the work-energy theorem also supplies an answer to less simple situations. The penetration of a bullet, fired vertically upward into a block of wood, is discussed in one section of Asif Shakur’s recent article [“Bullet-Block Science Video Puzzle.” The Physics Teacher (January 2015) 53(1): 15-16]. If the bullet is fired dead center into the block, it loses all its kinetic energy and penetrates slightly farther than if fired off-center. The reason is that if the bullet hits off-center, it has a little kinetic energy after it stops penetrating, because the block rotates. The work-energy theorem implies that a smaller change in kinetic energy results in a smaller penetration. You will understand more of the physics in this interesting article after you finish reading Angular Momentum.

Learn more about work and energy in this PhET simulation (https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/the-ramp) called “the ramp.” Try changing the force pushing the box and the frictional force along the incline. The work and energy plots can be examined to note the total work done and change in kinetic energy of the box.