5.2: Invariance of Physical Laws

- Last updated

- Aug 11, 2021

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 45981

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the theoretical and experimental issues that Einstein’s theory of special relativity addressed.

- State the two postulates of the special theory of relativity.

Suppose you calculate the hypotenuse of a right triangle given the base angles and adjacent sides. Whether you calculate the hypotenuse from one of the sides and the cosine of the base angle, or from the Pythagorean theorem, the results should agree. Predictions based on different principles of physics must also agree, whether we consider them principles of mechanics or principles of electromagnetism.

Albert Einstein pondered a disagreement between predictions based on electromagnetism and on assumptions made in classical mechanics. Specifically, suppose an observer measures the velocity of a light pulse in the observer’s own rest frame; that is, in the frame of reference in which the observer is at rest. According to the assumptions long considered obvious in classical mechanics, if an observer measures a velocity →v in one frame of reference, and that frame of reference is moving with velocity →u past a second reference frame, an observer in the second frame measures the original velocity as

→v′=→v+→u.

This sum of velocities is often referred to as Galilean relativity. If this principle is correct, the pulse of light that the observer measures as traveling with speed c travels at speed c + u measured in the frame of the second observer. If we reasonably assume that the laws of electrodynamics are the same in both frames of reference, then the predicted speed of light (in vacuum) in both frames should be

c=1/√ϵ0μ0.

Each observer should measure the same speed of the light pulse with respect to that observer’s own rest frame. To reconcile difficulties of this kind, Einstein constructed his special theory of relativity, which introduced radical new ideas about time and space that have since been confirmed experimentally.

Inertial Frames

All velocities are measured relative to some frame of reference. For example, a car’s motion is measured relative to its starting position on the road it travels on; a projectile’s motion is measured relative to the surface from which it is launched; and a planet’s orbital motion is measured relative to the star it orbits. The frames of reference in which mechanics takes the simplest form are those that are not accelerating. Newton’s first law, the law of inertia, holds exactly in such a frame.

Definition: Inertial Reference Frame

An inertial frame of reference is a reference frame in which a body at rest remains at rest and a body in motion moves at a constant speed in a straight line unless acted upon by an outside force.

For example, to a passenger inside a plane flying at constant speed and constant altitude, physics seems to work exactly the same as when the passenger is standing on the surface of Earth. When the plane is taking off, however, matters are somewhat more complicated. In this case, the passenger at rest inside the plane concludes that a net force F on an object is not equal to the product of mass and acceleration, ma. Instead, F is equal to ma plus a fictitious force. This situation is not as simple as in an inertial frame. Special relativity handles accelerating frames as a constant and velocities as relative to the observer. General relativity treats both velocity and acceleration as relative to the observer, thus making the use of curved space-time.

Einstein’s First Postulate

Not only are the principles of classical mechanics simplest in inertial frames, but they are the same in all inertial frames. Einstein based the first postulate of his theory on the idea that this is true for all the laws of physics, not merely those in mechanics.

FIRST POSTULATE OF SPECIAL RELATIVITY

The laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference.

This postulate denies the existence of a special or preferred inertial frame. The laws of nature do not give us a way to endow any one inertial frame with special properties. For example, we cannot identify any inertial frame as being in a state of “absolute rest.” We can only determine the relative motion of one frame with respect to another.

There is, however, more to this postulate than meets the eye. The laws of physics include only those that satisfy this postulate. We will see that the definitions of energy and momentum must be altered to fit this postulate. Another outcome of this postulate is the famous equation E=mc2, which relates energy to mass.

Einstein’s Second Postulate

The second postulate upon which Einstein based his theory of special relativity deals with the speed of light. Late in the nineteenth century, the major tenets of classical physics were well established. Two of the most important were the laws of electromagnetism and Newton’s laws. Investigations such as Young’s double-slit experiment in the early 1800s had convincingly demonstrated that light is a wave. Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism implied that electromagnetic waves travel at c=3.00×108m/s in a vacuum, but they do not specify the frame of reference in which light has this speed. Many types of waves were known, and all travelled in some medium. Scientists therefore assumed that some medium carried the light, even in a vacuum, and that light travels at a speed c relative to that medium (often called “the aether”).

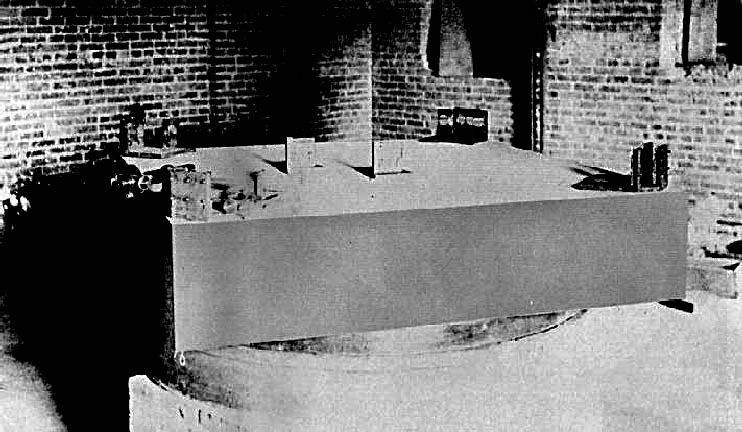

Starting in the mid-1880s, the American physicist A.A. Michelson, later aided by E.W. Morley, made a series of direct measurements of the speed of light. They intended to deduce from their data the speed v at which Earth was moving through the mysterious medium for light waves. The speed of light measured on Earth should have been c+v when Earth’s motion was opposite to the medium’s flow at speed u past the Earth, and c–v when Earth was moving in the same direction as the medium (Figure 5.2.1). The results of their measurements were startling.

The eventual conclusion derived from this result is that light, unlike mechanical waves such as sound, does not need a medium to carry it. Furthermore, the Michelson-Morley results implied that the speed of light c is independent of the motion of the source relative to the observer. That is, everyone observes light to move at speed c regardless of how they move relative to the light source or to one another. For several years, many scientists tried unsuccessfully to explain these results within the framework of Newton’s laws.

MICHELSON-MORLEY EXPERIMENT

The Michelson-Morley experiment demonstrated that the speed of light in a vacuum is independent of the motion of Earth about the Sun.

In addition, there was a contradiction between the principles of electromagnetism and the assumption made in Newton’s laws about relative velocity. Classically, the velocity of an object in one frame of reference and the velocity of that object in a second frame of reference relative to the first should combine like simple vectors to give the velocity seen in the second frame. If that were correct, then two observers moving at different speeds would see light traveling at different speeds. Imagine what a light wave would look like to a person traveling along with it (in vacuum) at a speed c. If such a motion were possible, then the wave would be stationary relative to the observer. It would have electric and magnetic fields whose strengths varied with position but were constant in time. This is not allowed by Maxwell’s equations. So either Maxwell’s equations are different in different inertial frames, or an object with mass cannot travel at speed c. Einstein concluded that the latter is true: An object with mass cannot travel at speed c. Maxwell’s equations are correct, but Newton’s addition of velocities is not correct for light.

Not until 1905, when Einstein published his first paper on special relativity, was the currently accepted conclusion reached. Based mostly on his analysis that the laws of electricity and magnetism would not allow another speed for light, and only slightly aware of the Michelson-Morley experiment, Einstein detailed his second postulate of special relativity.

SECOND POSTULATE OF SPECIAL RELATIVITY

Light travels in a vacuum with the same speed c in any direction in all inertial frames.

In other words, the speed of light has the same definite speed for any observer, regardless of the relative motion of the source. This deceptively simple and counterintuitive postulate, along with the first postulate, leave all else open for change. Among the changes are the loss of agreement on the time between events, the variation of distance with speed, and the realization that matter and energy can be converted into one another. We describe these concepts in the following sections.

Exercise 5.2.1

Explain how special relativity differs from general relativity.

- Answer

-

Special relativity applies only to objects moving at constant velocity, whereas general relativity applies to objects that undergo acceleration