5.3: The Second Condition for Equilibrium

- Page ID

- 48802

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the second condition that is necessary to achieve equilibrium.

- Explain torque and the factors on which it depends.

- Describe the role of torque in rotational mechanics.

Definition: Torque

The second condition necessary to achieve equilibrium involves avoiding accelerated rotation (maintaining a constant angular velocity. A rotating body or system can be in equilibrium if its rate of rotation is constant and remains unchanged by the forces acting on it. To understand what factors affect rotation, let us think about what happens when you open an ordinary door by rotating it on its hinges.

Several familiar factors determine how effective you are in opening the door (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). First of all, the larger the force, the more effective it is in opening the door—obviously, the harder you push, the more rapidly the door opens. Also, the point at which you push is crucial. If you apply your force too close to the hinges, the door will open slowly, if at all. Most people have been embarrassed by making this mistake and bumping up against a door when it did not open as quickly as expected. Finally, the direction in which you push is also important. The most effective direction is perpendicular to the door—we push in this direction almost instinctively.

The magnitude, direction, and point of application of the force are incorporated into the definition of the physical quantity called torque. Torque is the rotational equivalent of a force. It is a measure of the effectiveness of a force in changing or accelerating a rotation (changing the angular velocity over a period of time). For forces applied strictly at right angles, we can express the magnitude of the torque in equation form as

\[\tau = r_{\perp}F \]

where \(\tau\) (the Greek letter tau) is the symbol for torque, \(r_{\perp}\) is the perpendicular lever arm, and \(F\) is the magnitude of the force.

The perpendicular lever arm \(r_{\perp}\) is the shortest distance from the pivot point to the line along which \(F\) acts. Note that the line segment that defines the distance \(r_{\perp}\) is perpendicular to \(F\), as its name implies.

The SI unit of torque is newtons times meters, usually written as N\(\cdot\)m. For example, if you push perpendicular to the door with a force of 40 N at a distance of 0.800 m from the hinges, you exert a torque of 32 N\(\cdot\)m (0.800 m \(\times\) 40 N) relative to the hinges. If you reduce the force to 20 N, the torque is reduced to 16 N\(\cdot\)m, and so on.

The torque is always calculated with reference to some chosen pivot point. For the same applied force, a different choice for the location of the pivot will give you a different value for the torque. Any point in any object can be chosen to calculate the torque about that point. The object may not actually pivot about the chosen “pivot point.”

Note that for rotation in a plane, torque has two possible directions. Torque is either clockwise or counterclockwise relative to the chosen pivot point.

Now, the second condition necessary to achieve equilibrium is that the net external torque on a system must be zero. An external torque is one that is created by an external force. You can choose the point around which the torque is calculated. The point can be the physical pivot point of a system or any other point in space—but it must be the same point for all torques. If the second condition (net external torque on a system is zero) is satisfied for one choice of pivot point, it will also hold true for any other choice of pivot point in or out of the system of interest. The second condition necessary to achieve equilibrium is stated in equation form as

\[net \, \tau = 0\]

where net means total. Torques which are in opposite directions are assigned opposite signs. A common convention is to call counterclockwise (ccw) torques positive and clockwise (cw) torques negative.

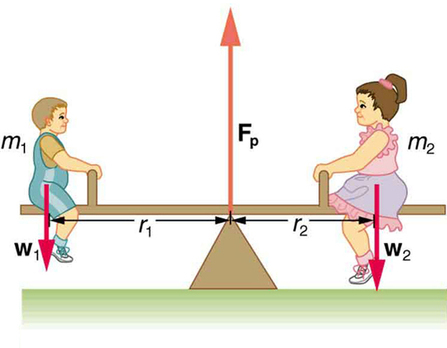

When two children balance a seesaw as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), they satisfy the two conditions for equilibrium. Most people have perfect intuition about seesaws, knowing that the lighter child must sit farther from the pivot and that a heavier child can keep a lighter one off the ground indefinitely.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): She Saw Torques On A Seesaw

The two children shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) are balanced on a seesaw of negligible mass. (This assumption is made to keep the example simple—more involved examples will follow.) The first child has a mass of 26.0 kg and sits 1.60 m from the pivot.

- If the second child has a mass of 32.0 kg, how far is she from the pivot?

- What is \(F_p\), the supporting force exerted by the pivot?

Strategy

Both conditions for equilibrium must be satisfied. In part (a), we are asked for a distance; thus, the second condition (regarding torques) must be used, since the first (regarding only forces) has no distances in it. To apply the second condition for equilibrium, we first identify the system of interest to be the seesaw plus the two children. We take the supporting pivot to be the point about which the torques are calculated. We then identify all external forces acting on the system.

Solution (a)

The three external forces acting on the system are the weights of the two children and the supporting force of the pivot. Let us examine the torque produced by each. Torque is defined to be

\[\tau = r_{\perp}F\nonumber\]

The torques exerted by the three forces are first,

\[\tau_1 = r_1w_1\nonumber\]

second,

\[\tau_2 = -r_2w_2\nonumber\]

and third,

\[ \begin{align*} \tau_p &= r_pF_p \\[5pt] &= 0 \cdot F_p \\[5pt] &= 0. \end{align*}\]

Note that a minus sign has been inserted into the second equation because this torque is clockwise and is therefore negative by convention. Since \(F_p\) acts directly on the pivot point, the distance \(r_p\) is zero. A force acting on the pivot cannot cause a rotation, just as pushing directly on the hinges of a door will not cause it to rotate. Now, the second condition for equilibrium is that the sum of the torques on both children is zero. Therefore

\[\tau_2 = -\tau_1,\nonumber\]

or

\[r_2w_2 = r_1w_1.\nonumber\]

Weight is mass times the acceleration due to gravity. Entering \(mg\) for \(w\), we get

\[r_2m_2g = r_1w_1g.\nonumber\]

Solve this for the unknown \(r_2\):

\[r_2 = r_1\dfrac{m_1}{m_2}.\nonumber\]

The quantities on the right side of the equation are known; thus, \(r_2\) is

\[ \begin{align*} r_2 &= (1.60 \, m)\dfrac{26.0 \, kg}{32.0 \, kg} \\[5pt] &= 1.30 \, m \end{align*}\]

As expected, the heavier child must sit closer to the pivot (1.30 m versus 1.60 m) to balance the seesaw.

Solution (b)

This part asks for a force \(F_p\). The easiest way to find it is to use the first condition for equilibrium, which is

\[net \, F = 0.\nonumber\]

The forces are all vertical, so that we are dealing with a one-dimensional problem along the vertical axis; hence, the condition can be written as

\[net \, F_y = 0 \nonumber\]

where we again call the vertical axis the y-axis. Choosing upward to be the positive direction, and using plus and minus signs to indicate the directions of the forces, we see that

\[F_p - w_1 - w_2 = 0.\nonumber\]

This equation yields what might have been guessed at the beginning:

\[F_p = w_1 + w_2. \nonumber\]

So, the pivot supplies a supporting force equal to the total weight of the system:

\[F_p = m_1g + m_2g. \nonumber\]

Entering known values gives

\[ \begin{align*} F_p &= (26.0 \, kg)(9.80 \, m/s^2) + (32.0 \, kg)(9.80 \, m/s^2) \\[5pt] &= 568 \, N. \end{align*}\]

Discussion

The two results make intuitive sense. The heavier child sits closer to the pivot. The pivot supports the weight of the two children. Part (b) can also be solved using the second condition for equilibrium, since both distances are known, but only if the pivot point is chosen to be somewhere other than the location of the seesaw’s actual pivot!

Several aspects of the preceding example have broad implications. First, the choice of the pivot as the point around which torques are calculated simplified the problem. Since \(F_p\) is exerted on the pivot point, its lever arm is zero. Hence, the torque exerted by the supporting force \(F_p\) is zero relative to that pivot point. The second condition for equilibrium holds for any choice of pivot point, and so we choose the pivot point to simplify the solution of the problem.

Second, the acceleration due to gravity canceled in this problem, and we were left with a ratio of masses. This will not always be the case. Always enter the correct forces—do not jump ahead to enter some ratio of masses.

Third, the weight of each child is distributed over an area of the seesaw, yet we treated the weights as if each force were exerted at a single point. This is not an approximation—the distances \(r_{\perp}\) and \(r_2\) are the distances to points directly below the center of gravity of each child. As we shall see in the next section, the mass and weight of a system can act as if they are located at a single point.

Finally, note that the concept of torque has an importance beyond static equilibrium. Torque plays the same role in rotational motion that force plays in linear motion. We will examine this in the next chapter.

Take-Home Experiment

- Take a piece of modeling clay and put it on a table, then mash a cylinder down into it so that a ruler can balance on the round side of the cylinder while everything remains still. Put a penny 8 cm away from the pivot. Where would you need to put two pennies to balance? Three pennies?

Summary

- The second condition assures those torques are also balanced. Torque is the rotational equivalent of a force in producing a rotation and is defined to be \[\tau = r_{\perp}F \nonumber\] where \(\tau\) is torque, \(r_{\perp}\) is the perpendicular distance from the pivot point to the line containing the point where the force is applied, and \(F\) is magnitude of the force.

- The perpendicular lever arm \(r_{\perp}\) is the shortest distance from the pivot point to the line along which \(F\) acts. The SI unit for torque is the newton-meter N\(\cdot\)m. The second condition necessary to achieve equilibrium is that the net external torque on a system must be zero: \[ net \, \tau = 0 \nonumber\] By convention, counterclockwise torques are positive, and clockwise torques are negative.

Glossary

- torque

- turning or twisting effectiveness of a force

- perpendicular lever arm

- the shortest distance from the pivot point to the line along which \(F\) lies

- SI units of torque

- newton times meters, usually written as N·m

- center of gravity

- the point where the total weight of the body is assumed to be concentrated

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Peter Urone (Professor Emeritus at California State University, Sacramento) and Roger Hinrichs (State University of New York, College at Oswego) with Contributing Authors: Kim Dirks (University of Auckland) and Manjula Sharma (University of Sydney). This work is licensed by OpenStax University Physics under a Creative Commons Attribution License (by 4.0).