12.2: The First Law of Thermodynamics

- Page ID

- 47083

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the first law of thermodynamics.

- Describe how conservation of energy relates to the first law of thermodynamics.

- Identify instances of the first law of thermodynamics working in everyday situations, including biological metabolism.

- Calculate changes in the internal energy of a system, after accounting for heat transfer and work done.

If we are interested in how heat transfer is converted into doing work, then the conservation of energy principle is important. The first law of thermodynamics applies the conservation of energy principle to systems where heat transfer and doing work are the methods of transferring energy into and out of the system.

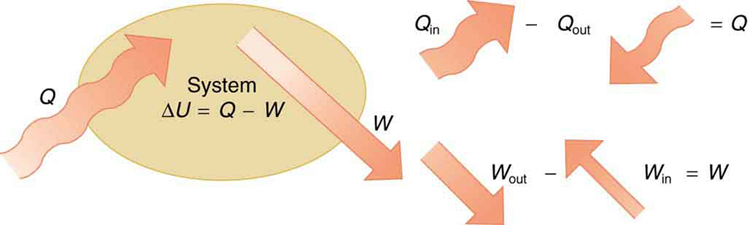

The first law of thermodynamics states that the change in internal energy of a system equals the net heat transfer into the system minus the net work done by the system. In equation form, the first law of thermodynamics is

\[\Delta U = Q - W. \label{first}\]

Here \(\Delta U\) is the change in internal energy \(U\) of the system. \(Q\) is the net heat transferred into the system—that is, \(Q\) is the sum of all heat transfer into and out of the system. \(W\) is the net work done by the system—that is, \(W\) is the sum of all work done on or by the system. We use the following sign conventions: if \(Q\) is positive, then there is a net heat transfer into the system; if \(W\) is positive, then there is net work done by the system. So positive \(Q\) adds energy to the system and positive \(W\) takes energy from the system. Thus \(\Delta U = Q - W\). Note also that if more heat transfer into the system occurs than work done, the difference is stored as internal energy. Heat engines are a good example of this—heat transfer into them takes place so that they can do work (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). We will now examine \(Q, \, W\) and \(\Delta U\) further.

LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS AND LAW OF CONSERVATION OF ENERGY

The first law of thermodynamics is actually the law of conservation of energy stated in a form most useful in thermodynamics. The first law gives the relationship between heat transfer, work done, and the change in internal energy of a system.

Heat Q and Work W

Heat transfer \(Q\) and doing work \(W\) are the two everyday means of bringing energy into or taking energy out of a system. The processes are quite different. Heat transfer, a less organized process, is driven by temperature differences. Work, a quite organized process, involves a macroscopic force exerted through a distance. Nevertheless, heat and work can produce identical results.For example, both can cause a temperature increase. Heat transfer into a system, such as when the Sun warms the air in a bicycle tire, can increase its temperature, and so can work done on the system, as when the bicyclist pumps air into the tire. Once the temperature increase has occurred, it is impossible to tell whether it was caused by heat transfer or by doing work. This uncertainty is an important point. Heat transfer and work are both energy in transit—neither is stored as such in a system. However, both can change the internal energy \(U\) of a system. Internal energy is a form of energy completely different from either heat or work.

Internal Energy U

We can think about the internal energy of a system in two different but consistent ways. The first is the atomic and molecular view, which examines the system on the atomic and molecular scale. The internal energy \(U\) of a system is the sum of the kinetic and potential energies of its atoms and molecules. Recall that kinetic plus potential energy is called mechanical energy. Thus internal energy is the sum of atomic and molecular mechanical energy. Because it is impossible to keep track of all individual atoms and molecules, we must deal with averages and distributions. A second way to view the internal energy of a system is in terms of its macroscopic characteristics, which are very similar to atomic and molecular average values.

Macroscopically, we define the change in internal energy \(\Delta U\) to be that given by the first law of thermodynamics (Equation \ref{first}): \[\Delta U = Q - W \nonumber\]

Many detailed experiments have verified that \(\Delta U = Q - W\), where \(\Delta U\) is the change in total kinetic and potential energy of all atoms and molecules in a system. It has also been determined experimentally that the internal energy \(U\) of a system depends only on the state of the system and not how it reached that state. More specifically, \(U\) is found to be a function of a few macroscopic quantities (pressure, volume, and temperature, for example), independent of past history such as whether there has been heat transfer or work done. This independence means that if we know the state of a system, we can calculate changes in its internal energy \(U\) from a few macroscopic variables.

MACROSCOPIC vs. MICROSCOPIC

In thermodynamics, we often use the macroscopic picture when making calculations of how a system behaves, while the atomic and molecular picture gives underlying explanations in terms of averages and distributions. We shall see this again in later sections of this chapter. For example, in the topic of entropy, calculations will be made using the atomic and molecular view.

To get a better idea of how to think about the internal energy of a system, let us examine a system going from State 1 to State 2. The system has internal energy \(U_1\) in State 1, and it has internal energy \(U_2\) in State 2, no matter how it got to either state. So the change in internal energy

\[\Delta U = U_2 - U_1\]

is independent of what caused the change. In other words, \(\delta U\) is independent of path. By path, we mean the method of getting from the starting point to the ending point. Why is this independence important? Both \(Q\) and \(W\) depend on path, but \(\Delta U\) does not (Equation \ref{first}). This path independence means that internal energy \(U\) is easier to consider than either heat transfer or work done.

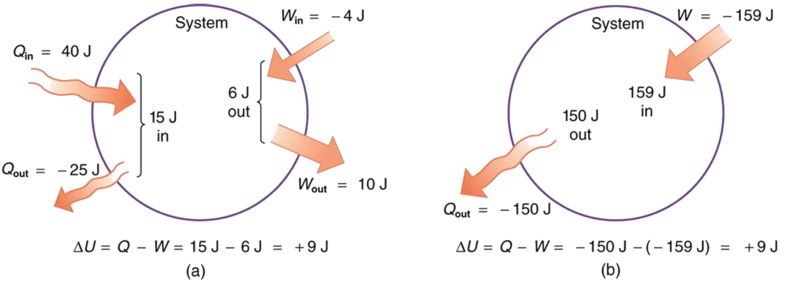

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Change in Internal Energy - The Same Change in \(U\) is Produced by Two Different Processes

- Suppose there is heat transfer of 40.00 J to a system, while the system does 10.00 J of work. Later, there is heat transfer of 25.00 J out of the system while 4.00 J of work is done on the system. What is the net change in internal energy of the system?

- What is the change in internal energy of a system when a total of 150.00 J of heat transfer occurs out of (from) the system and 159.00 J of work is done on the system (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\))?

Strategy

In part (a), we must first find the net heat transfer and net work done from the given information. Then the first law of thermodynamics (Equation \ref{first}).

can be used to find the change in internal energy. In part (b), the net heat transfer and work done are given, so the equation can be used directly.

Solution for (a)

The net heat transfer is the heat transfer into the system minus the heat transfer out of the system, or

\[ \begin{align*} Q &= 40.00 \, J - 25.00 \, J \\[5pt] &= 15.00 \, J \end{align*}\]

Similarly, the total work is the work done by the system minus the work done on the system, or

\[ \begin{align*} W &= 10.00 \, J - 4.00 \, J \\[5pt] &= 6.00 \, J. \end{align*}\]

Discussion on (a)

No matter whether you look at the overall process or break it into steps, the change in internal energy is the same.

Solution for (b)

Here the net heat transfer and total work are given directly to be \(Q = -150.00 \, J\) and \(W = -159.00 \, J\), so that

\[ \begin{align*} \Delta U &= Q - W = -150.00 - (-159.00) \\[5pt] &= 9.00 \, J. \end{align*}\]

Discussion on (b)

A very different process in part (b) produces the same 9.00-J change in internal energy as in part (a). Note that the change in the system in both parts is related to \(\Delta U\) and not to the individual \(Q\)s or \(W\)s involved. The system ends up in the same state in both (a) and (b). Parts (a) and (b) present two different paths for the system to follow between the same starting and ending points, and the change in internal energy for each is the same—it is independent of path.

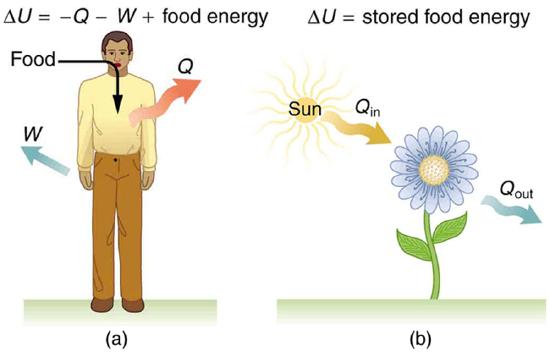

Human Metabolism and the First Law of Thermodynamics

Human metabolism is the conversion of food into heat transfer, work, and stored fat. Metabolism is an interesting example of the first law of thermodynamics in action. We now take another look at these topics via the first law of thermodynamics. Considering the body as the system of interest, we can use the first law to examine heat transfer, doing work, and internal energy in activities ranging from sleep to heavy exercise. What are some of the major characteristics of heat transfer, doing work, and energy in the body? For one, body temperature is normally kept constant by heat transfer to the surroundings. This means \(Q\) is negative. Another fact is that the body usually does work on the outside world. This means \(W\) is positive. In such situations, then, the body loses internal energy, since \(\Delta U = Q - W\) is negative.

Now consider the effects of eating. Eating increases the internal energy of the body by adding chemical potential energy (this is an unromantic view of a good steak). The body metabolizes all the food we consume. Basically, metabolism is an oxidation process in which the chemical potential energy of food is released. This implies that food input is in the form of work. Food energy is reported in a special unit, known as the Calorie. This energy is measured by burning food in a calorimeter, which is how the units are determined.

In chemistry and biochemistry, one calorie (spelled with a lowercase c) is defined as the energy (or heat transfer) required to raise the temperature of one gram of pure water by one degree Celsius. Nutritionists and weight-watchers tend to use the dietary calorie, which is frequently called a Calorie (spelled with a capital C). One food Calorie is the energy needed to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius. This means that one dietary Calorie is equal to one kilocalorie for the chemist, and one must be careful to avoid confusion between the two.

Again, consider the internal energy the body has lost. There are three places this internal energy can go—to heat transfer, to doing work, and to stored fat (a tiny fraction also goes to cell repair and growth). Heat transfer and doing work take internal energy out of the body, and food puts it back. If you eat just the right amount of food, then your average internal energy remains constant. Whatever you lose to heat transfer and doing work is replaced by food, so that, in the long run, \(\Delta U = 0\). If you overeat repeatedly, then \(\Delta U\) is always positive, and your body stores this extra internal energy as fat. The reverse is true if you eat too little. If \(\Delta U\) is negative for a few days, then the body metabolizes its own fat to maintain body temperature and do work that takes energy from the body. This process is how dieting produces weight loss.

Life is not always this simple, as any dieter knows. The body stores fat or metabolizes it only if energy intake changes for a period of several days. Once you have been on a major diet, the next one is less successful because your body alters the way it responds to low energy intake. Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the rate at which food is converted into heat transfer and work done while the body is at complete rest. The body adjusts its basal metabolic rate to partially compensate for over-eating or under-eating. The body will decrease the metabolic rate rather than eliminate its own fat to replace lost food intake. You will chill more easily and feel less energetic as a result of the lower metabolic rate, and you will not lose weight as fast as before. Exercise helps to lose weight, because it produces both heat transfer from your body and work, and raises your metabolic rate even when you are at rest. Weight loss is also aided by the quite low efficiency of the body in converting internal energy to work, so that the loss of internal energy resulting from doing work is much greater than the work done.It should be noted, however, that living systems are not in thermal equilibrium.

The body provides us with an excellent indication that many thermodynamic processes are irreversible. An irreversible process can go in one direction but not the reverse, under a given set of conditions. For example, although body fat can be converted to do work and produce heat transfer, work done on the body and heat transfer into it cannot be converted to body fat. Otherwise, we could skip lunch by sunning ourselves or by walking down stairs. Another example of an irreversible thermodynamic process is photosynthesis. This process is the intake of one form of energy—light—by plants and its conversion to chemical potential energy. Both applications of the first law of thermodynamics are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). One great advantage of conservation laws such as the first law of thermodynamics is that they accurately describe the beginning and ending points of complex processes, such as metabolism and photosynthesis, without regard to the complications in between.

Summary

The table presents a summary of terms relevant to the first law of thermodynamics.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| \(U\) | Internal energy—the sum of the kinetic and potential energies of a system’s atoms and molecules. Can be divided into many subcategories, such as thermal and chemical energy. Depends only on the state of a system (such as its \(P\), \(V\) and \(T\), not on how the energy entered the system. Change in internal energy is path independent. |

| \(Q\) | Heat—energy transferred because of a temperature difference. Characterized by random molecular motion. Highly dependent on path. \(Q\) entering a system is positive. |

| \(W\) | Work—energy transferred by a force moving through a distance. An organized, orderly process. Path dependent. \(W\) done by a system (either against an external force or to increase the volume of the system) is positive. |

- The first law of thermodynamics is given as \(\Delta U = Q - W\), where \(\Delta U\) is the change in internal energy of a system, \(Q\) is the net heat transfer (the sum of all heat transfer into and out of the system), and \(W\) is the net work done (the sum of all work done on or by the system).

- Both \(Q\) and \(W\) are energy in transit; only \(\Delta U\) represents an independent quantity capable of being stored.

- The internal energy \(U\) of a system depends only on the state of the system and not how it reached that state.

- Metabolism of living organisms, and photosynthesis of plants, are specialized types of heat transfer, doing work, and internal energy of systems.

Glossary

- first law of thermodynamics

- states that the change in internal energy of a system equals the net heat transfer into the system minus the net work done by the system

- internal energy

- the sum of the kinetic and potential energies of a system’s atoms and molecules

- human metabolism

- conversion of food into heat transfer, work, and stored fat

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Peter Urone (Professor Emeritus at California State University, Sacramento) and Roger Hinrichs (State University of New York, College at Oswego) with Contributing Authors: Kim Dirks (University of Auckland) and Manjula Sharma (University of Sydney). This work is licensed by OpenStax University Physics under a Creative Commons Attribution License (by 4.0).