3.12: Torque, Angular Momentum and a Moving Point

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

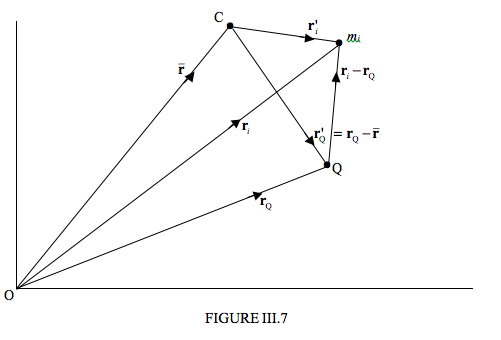

In Figure III.7 I draw the particle mi, which is just one of n particles, n−1 of which I haven’t drawn and are scattered around in 3-space. I draw an arbitrary origin O, the centre of mass C of the system, and another point Q, which may (or may not) be moving with respect to O. The question I am going to ask is: Does the equation ˙L=τ apply to the point Q? It obviously does if Q is stationary, just as it applies to O. But what if Q is moving? If it does not apply, just what is the appropriate relation?

The theorem that we shall prove – and interpret - is

˙LQ=τQ+Mr′QרrQ.

We start:

LQ=∑(ri−rQ)×[mi(vi−vQ)]

∴˙LQ=∑(ri−rQ)×mi(˙vi−˙vQ)+∑(˙ri−˙rQ)×mi(vi−vQ).

The second term is zero, because ˙r=v

Continue:

˙L=∑(ri−rQ)×mi˙vi−∑miri×˙vQ+∑mirQ×˙vQ

Now mi˙vi=Fi, so that the first term is just τQ

Continue:

˙L=τQ−∑miri×dotvQ+∑MirQ×dotvQ

=τQ−M¯rרrQ+MrQרrQ

=τQ+M(rQ−¯r)רrQ

∴˙LQ=τQ+Mr′QרrQQ.E.D

Thus in general, ˙LQ≠τQ, but ˙LQ=τQ under any of the following three circumstances:

- r′Q=0 - that is, Q coincides with C.

- ¨rQ=0 - that is, Q is not accelerating.

- ¨rQ and r′Q are parallel, which would happen, for example, if O were a centre of attraction or repulsion and Q were accelerating towards or away from O.